LONG LOST TWINS, PART III

To start off, a quick revisit of Part I of this series. I’ve found another example of the same sphinx and pelican with urn design (I knew I had seen one more, I just had to remember where.) This one is also part of the Hermitage collection, a piece of lacis (darned net). Note that due to problems with my blogging engine, only the museum citation will work as a link to the artifact page.

Valence Embroidered with a Grotesque Motif. Hermitage Museum. 16th century, Italy.

So now we have a second 16th century example of this design, and proof that these patterns were used to execute multiple needlework styles. There are some differences between the details of the lacis and the voided embroidery examples I posted earlier this week. The lacis work is closer to the other Hermitage piece – the simpler of the two – but that could be because lacis does not lend itself to the fine detail that can be worked in double running.

Now on to today’s multiple. This is a fun one.

First, here’s our basic design worked as a single width strip.

Band. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accession 09.50.1. 16th-17th century, Italy. 3.75 x 13.25 inches (9.5 x 33.7 cm)

And here is the same design but done up as a double width strip:

Fragment. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accession 09.50.1366. 16th century, Italy. 11.25 x 14.75 inches (28.6 x 37.5cm)

There are some minor differences in treatment between them. I can’t tell what stitch is used for the voided background of the second, but whatever it is, it is not the pulled thread mesh of the first example. And some of the interior elements of the design – the Y an O centers at the reflection lines – are filled in in the second sample, while they’re left unworked in the single width band. It may also be possible that the outline on the second sample was worked in a contrasting color silk because it appears to be darker and more crisp than the outline in the narrower example. And of course, the companion edging treatments are totally different.

But that’s not all. Here are two more examples of the same pattern, also with their Y and O centers left unworked:

Punto di Milano. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Accession 11.2879. No date, probably Italian. 7 9/16 x 18 7/8 inches (19.2 x 48 cm).

Insertion with Border. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accession 12.9.2. Greek Islands. 7.5 x 18.5 inches (19.1 x 47 cm).

Now these two are EXTREMELY close in width, proportions, background treatment, count of the main design, and of the border. Even the placement of the little dots in the border element are identical. Both were collected between 1900 and 1920, the MFA’s by D. Waldo Ross (active around that time); and the MMoA’s originating from F Fischbach in Wiesbaden, Germany in 1909.

I believe that these two are actually and truly long-lost twins. It would not be impossible for these two pieces to have been cut from the same original artifact, or from a closely matched set of originals (like two of a set of multiple matching coverpanes – sort of like oversized napkin/towels). The two snippets were thens old to two different well-heeled collectors.

As to style, unlike the second item above, the outlines of our two twins are clearly not worked in a contrasting color. This piece also has a rather nifty and individualized border, created specifically to match the center strip. Sprigs of the main design’s foliage and center element are echoed in the companion edging.

Note that in NONE of these samples does the count of the companion narrow edging have anything to do with the count of the main panel repeat. This is pretty much universal. Modern attempts to align the repeats of edging and main strip are over-fastidious efforts, a practice not seen in historical samples. To my eye aligning border and main strip removes a bit of visual spontaneity, making the whole into a more static entity. But that’s my just own aesthetic opinion. Your mileage may vary, and your own tolerance for visual disorder might be lower than mine. All is good.

What conclusions can we draw from this set? Again, minor variations in working method were totally at at the discretion of the stitcher. There were then like there are now, no embroidery police. Narrow borders were also chosen independent of the main design, and might or might not match the style or design elements of the center strip. And finally – mirroring strips to make wider bands is a totally historically legitimate method of working a deeper strip.

On dating and provenance, again these designs were very conservative, varying little over time. We’ve got another 100 years or so to play with if we go by the museum dates. Plus this won’t be the last time we’ll see pieces attributed variously as being of Italian or Greek origin. There was a very lively trade in the region, and these pieces are very hard to pin down to just one place. Plus Greek Island embroideries retained many of these patterns in active vocabulary long after similar designs had passed out of high style in Italy. Not all traditional Greek stitchery patterns are of 16th-17th century origin of course, but some do share a common lineage with Italian works of the same time.

For the record, this pattern (in single width) is among those I’m hoping to present in TNCM2.

LONG LOST TWINS, PART II

To continue our museum hopping trip viewing similar patterns, here’s another cluster Again, this is a group that to my limited knowledge is NOT based upon a graph appearing in an extant 15th ro 16th century modelbook (but I haven’t seen them all).

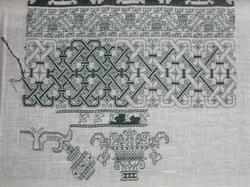

I’ve graphed the MMA and MFA examples (#2 and #3) for inclusion in TNCM2. I also stitched #2 in long armed cross stitch, on my big blackwork sampler:

Compare my proportions to the museum examples to see the minor distortion caused by the not-quite-even weave grounds of the historical examples, especially #1.

#1 from the PMA is cited as being worked in silk using cross and eyelet stitches (trapunto). The MFA cites #2 as being stitched in “Punto di Milano,” which is a term they use for a family of pulled thread techniques that produces a mesh-like appearance, often by use of two-sided Italian cross stitch, pulled very tightly. It’s more commonly found as a background in voided work, but pops up for foreground elements and accents, too. There is no consensus among museums on what this technique should be called. To complicate matters, there are several ways of producing the overstitched mesh background look, both single and double sided. Still the execution of these are very close, and both look to have been done using pulled thread technique rather than a withdrawn thread method.

But #1 and #2 are not pieces of the same artifact. I’ve confirmed counts between them. There are enough small differences in strip width, ground cloth thread count proportions, stitching and minor pattern details to conclude that #1 and #2 are not twins separated after birth. But they are so close that I’d opine that they were probably stitched from the same source – pattern collection sampler, printed broadside, hand-drawn pattern, or source artifact. There’s even a remote possibility that one of these is the paradigm for the other. We can’t say for sure, all we can do is note that they’re children of the same family.

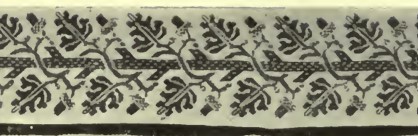

Now #3 and #4 might be more closely related. The width measurement, count, proportions, form and color placement on them are extremely close. Even those nasty little skips that give the tree branch bark its texture are spot on exact in placement between the two pieces. But I can’t say for certain that they are either pieces of the same original, or photos of the same artifact. Pieces have moved between museums before, and even the most scholarly author can make a mistake in attribution. The problem is the accompanying descriptions. #3 is in Punto di Milano. But the Kendrick-Holme book specifies that #4 is “embroidered with red and green floss silks in satin and double running stitches.” Again, attributions might not be correct. I wish I could find out if #4 is still in the V&A, and get a closer look at it.

So to sum up, again we’ve got a recognizable and stable pattern, possibly spanning centuries of active use. I think the attribution on #1 is a bit early, but I have no proof. We’ve also got two and possibly three different methods of execution, and evidence that variants of the same pattern were worked in both monochrome and multiple colors. We can posit that multicolor variants came later, but we cannot flatly conclude that monochrome came first, due to the broad and overlapping range of dates given for these pieces (with the 15th century date discounted as a possibly questionable outlier).

There are lots more of these in my notebooks. I find this fascinating, but I realize that not everyone is an uber-stitch-geek like me. Please let me know if you’re bored to tears, or if you’d like to see more examples of patterns over time.

YAAY FOR MONTENEGRIN; LONG LOST TWINS PART I

Work continues on my long green sampler. I was a bit of a stall last week, but with the help of the excellent Autopsy of the Montenegrin Stitch, Exhumed by Amy Mitten, I’ve forged on ahead. The Montenegrin is what I’m using for the dark accent stripes in the interlace:

Autopsy is a small flip book that contains nothing but diagrams for two Montenegrin stitch forms, showing the order and logic of the individual stitches. How tough can that be? Plenty tough. What the book lays out is the stitch sequence for EVERY junction where horizontal, vertical and diagonals meet. As you can see from my piece, there are lots of junctions possible! This is a boutique item to be sure – not everyone leaps in and rolls around in this particular stitch style, but if you are planning a project using it, the book is well worth its its price.

It’s no secret that I’m nearing completion of my own book. I’ve got about 60 plates of patterns done. 58 of them are complete. I may or may not expand that to 62 for publication. I have to make some decisions on some out-takes and patterns that span multiple pages. I have the companion “about” pages written. I’ve got the bibliography done. I’m working on the introduction now. And as I do so, I’ll be posting related bits to String. I can’t include museum photos in the book without licensing them. But I can use links to those photos here. Much of this material is stuff I covered in my Schola lecture. But instead of running through the travelogue of styles and techniques, I want to start with the fun part. The “Long Lost Twins” examples.

Long Lost Twins Part I

The counted thread styles I’ve been working for the past three years are quite well represented in museums worldwide, largely thanks to those interested in historical embroidery between 1870 and World War II. This is the era that included both Freida Lipperheide whose pattern collection documented specific artifacts (published in 1880s), Louisa Pesel (a leading needlework researcher most active from around 1900 until her death in 1947), and Arthur Lotz who cataloged all extant modelbooks (published in 1933). There were countless other books on old lace and needlework, and collectors ranged all over Europe harvesting examples. Many of these collectors amassed impressive assemblages of artifacts, and their collections form the backbone of what’s available for view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Hermitage in St. Petersberg, the Philadelphia Museum of Art and others. We owe a lot to their diligence and enthusiasm.

However the collectors were rather more of the Indiana Jones school than we as modern stitching devotees would like. The pieces are not clearly associated with provenance or date. Often they are small snippets disassociated from the original integral artifact, so the exact nature of the item they adorned is open to discussion, and center strips that might have been used in combo with additional narrow edgings have been cut and removed from context. Styles and patterns were also relatively conservative, appearing over long spans of time. Unlike samplers which have an increasingly wide body of academic research documenting them, these (mostly) domestic embroideries have drawn lesser attention, probably because they are anonymous and problematic to date. I don’t claim to be an academic. I’m just a dilettante. But I can observe. And this series contains some of my observations.

But enough dry disclaimer. Here’s our first example of fun.

The image on the left is Valence Embroidered with a Grotesque Motif, now in the Hermitage Museum. They date it as 16th century, from Italy. It’s stitched in red silk on linen, with a pulled thread background to achieve a mesh like effect and double running stitch for the outlines and details. The whole piece is about 5×29 inches or 13x75cm, unclear if that’s with our without the fringe, or whether the photo shows the entire artifact. The Hermitage obtained this piece in 1923. The item on the right is Border, Accession 14.134.16a in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. They date it as a 17th century Italian work. I’ve only shown one repeat, but the whole two+ repeat artifact is shown on the museum photo. It’s 6.14 x 24.5 inches or 15.9 x 62.2 cm. It was acquired in 1914.

You have to admit, they’re pretty darned close. If anything the later work has a bit more detail than the earlier one (although the earlier piece shows more diligence in filling in the more difficult tiny background bits inside small diameter swirls. This usually not the way the generation to generation transcription of patterns works. Detail is usually lost, with chubby Renaissance cherubs devolving into the minimalist “boxers” on 17th century samplers. To date I have not seen this pattern in a period pattern book.

As to the iconography, the pelican vulning itself (pricking its breast to produce blood to feed its young) is a standard image of the time. The obvious allegory is self-sacrifice. The other two winged creatures are rather sphinx like to me – wings and feathers, heads of women, lion bodies. They appear to be either blowing pan-pipes or sipping on flowers, depending on which piece you are looking at. The well or giant urn and vegetative components are very standard. Large urns flanked by facing beasts or mythical figures are very common in weaving and other decorative arts of the 1500s and 1600s. So what I end up with is a piece extolling virtues of self-sacrifice and wisdom, with a vaguely feminine cast.

Now, why are these so close? I haven’t a clue. I do not know if work of this type was done at home by talented amateurs, or in workshops. The skill level to create these is relatively high by modern cross-stitch kit standards, but in truth it’s not all that difficult, and the majority of today’s dedicated counted thread stitchers would have minimal trouble achieving it. I have no doubt at all that non-professionals in the 1500s could have churned out this work in quantities sufficient to edge bed hangings, sheets, curtains, towels, or pillows. About all I can say is that they are not from the same original. There are enough minute differences between them both in pattern details and the way they were stitched to preclude them being from a matching set.

I also have no choice other than to rely on the museum’s dates. And so we see the weaknesses of the attributions inherited by the museums from the original collectors. Are they in fact close in date with one being rather late 1500s and the other being rather early 1600s? Are they contemporary, from one century or the other? No way for me to tell.

What were they originally used for? Again, these pieces are out of context. We don’t know. The Hermitage pegs theirs as being part of a valence, probably based on the presence of the fringe along the lower edge. Was this part of a bed suite? A good guess, but without pieces or fragments of the rest of the suite, there’s no way to tell. The Met’s sample is even harder to place for use. It’s been totally removed from its origins. If it had accompanying top and bottom borders (very common), or a fringe like the Hermitage piece, they’re long gone.

So what we have are two pieces officially dated up to 100 years apart, recognizably highly similar in design, worked in very similar materials and techniques, from the same general geographic area. The later one displays slightly more detail than the earlier example. We’ve got no unifying source of pattern that link them. My only conclusions are that these prove that patterns were re-used; that they were relatively conservative over time AS IF the workers were stitching from common source material either printed or stitched. I’d also say that small variations work to work validate similarly small deviations performed by modern stitchers wishing to replicate the style and design, but that’s just my own personal opinion.

I have lots more of these. Stay tuned!

SCHOLA TALK

No pix this week. The Resident Male took my preferred camera with him on a business trip overseas, and I’m not disposed to dump batteries down the gaping maw of the older camera in their joint absence.

I had a lot of fun at the Hrim Schola event in Quintavia (Marlborough, MA) this weekend past. I took both Elder and Younger Daughter, plus Younger Daughter’s Pal. The four of us did the full day of classes and workshops, pausing briefly between activities to nosh out on the offered foods and snacks. I thoroughly enjoyed the three sessions I attended – an overview of fleeces and spinning by Lady Ermengar; a lessons-learned lecture on Italian Renaissance era Perugia towels by Master Peregrine the Illuminator; and an introductory taste of withdrawn thread work given by Kasia Wasilewska. The towels come from the same period as my favorite stitching, and the motifs are very much akin to it. Whitework is on my agenda, especially the early forms of cut and withdrawn thread stitching. And anyone who’s followed here knows that knitting is my hobby-away-from-my hobby – the thing I do when I’m not stitching (and vice versa.)

The kids went to several other workshops on Viking wire weaving; basic chain mail construction (no rivets or soldering); Japanese Kumihimo braiding; combing and carding wool; hand sewing; and needle weaving. Adding in the lucets they’ve both acquired this year (plus the lucet technique book they picked up from Small Churl Books at the Schola), we now have infinitely more ways to play with string in all its forms.

As part of the day’s activities, I gave a whirlwind tour of some of the things I’ve stumbled across doing research for TNCM2.

The first part of the talk was a travelogue of some of the counted styles popular in the 1500-1650 time range. I touched on the difficulty of exact dating due to the nature of the major collections in museums – that they were mostly amassed between 1860 and 1920, by collectors whose boundless enthusiasm and interest was rather more greatly developed than their ability to pin down dates and provenances. I also mentioned that while my original goal had been to develop a chronology of techniques and styles, doing so crisply based on the meager attributions and origins was impossible. Maybe as 16th and 17th century edging and domestic embroidery scraps become as well known and appreciated as samplers, and are studied by academics armed with the latest in dating technology it will become easier, but for now chronology is rather mushy.

After the style stampede I glossed over uses – the usual: clothing, domestic linen (sheets, napery, coverpanes, cushions), liturgical items. I tried to show examples not commonly represented in books or on-line image collections.

Then the real fun began. I tried to show that some standard preconceptions about these works can be challenged in the artifact record. We looked at work that wasn’t just red or black (or blue or green); monochrome vs. polychrome works; mixed techniques; that historical linen was not always even weave by the modern definition; that stitching was most often done over 3×3 or 4×4 threads on finer linen than we use for modern 2z2 countwork. I showed examples of contrasting color outline voided pieces, and some works that were less concerned with adherence to precision pattern fidelity than they were with overall effect. And we looked at some pieces that while worked on the count, were probably drawn on the fabric freehand prior to stitching rather than being reproduced from a graph or previous piece of stitching.

After that it was a short move to the “treasure hunt” part of the talk. I have great fun finding and matching disparate works. I’ve found quite a few pieces that represent distinct pattern families. Some of these designs appear on snippets of finished works and also on specific historical samplers – not English didactic ones, on pieces I believe might have been sample sheets for professionals (my fave V&A sampler falls in this category). In other cases there are groups of finished snippets that were clearly worked from the same master pattern. Some of these have roots in German, Italian, French and English modelbooks. Others have no printed original that has descended to us, but are so close in base design that a common source must have existed. And other snippets, now widely scattered to different museums or private collections might in fact have come from the same origins, sold in small pieces to multiple collectors who visited the same European dealers.

The upshot of my talk is that there is far more variation in these pieces than modern stitchers might realize. That these variations enable a fair amount of play for those wishing to replicate a style. I’m a firm believer in studying the samples in order to internalize the deeper aesthetic and method, then using those vocabularies to produce work that is true to the time, without being a clone of a period piece. I don’t claim that my stitching embodies that ideal. My stuff is modern play-testing, assembled without regard for period aesthetic. Learning pieces at best, and not historical beyond the fact that they incorporate historical designs.

I got some good questions from the group. After TNCM2 is out, I’ll look into ateliers and professional vs. at-home stitching, and see what the academic literature has accumulated in the six or so years since the last time I went on a hunt for that info. I’ll also look more into materials, especially fingerspun floss silks. And I’ll be reworking some of the slides from the talk into blog posts, with source references, so that the small audience here can chime in, too.

I think the attendees enjoyed the talk, although in retrospect, I probably had way too much content for just one hour. I motored through at ramming speed, for sure. By the end they looked exhausted, and a bit overwhelmed. But that could have been my own exhaustion projecting itself onto them.

Needless to say, I had a great time. It was fun to find others interested in this stuff. I met quite a few people face to fact that I’d either not seen in 15 years, or who I have only known through on-line interaction (Hi guys!). I’m not a joiner, and am pretty solitary by nature. I tool along on my own, and have done so for decades. Blogging and boards bring some interaction with kindred spirits, sparks I truly appreciate. But giving the talk and interacting with the attendees was like sitting by a bonfire. If they enjoyed it half as much as I did, I’ll be extremely happy.

Oh. One last thing. Thanks to the group who put this together, running the event, scheduling the classes, manning the kitchen (very tasty!), and otherwise enabling the day. And thanks to Davey whose enthusiasm and encouragement goaded me into crawling out of my basement hole, and volunteering to do a class.

GREENS BOTH DARK AND LIVID

Laying down the double running outlines for the latest strip, with the intent of going back and filling in the Montenegrin cross stitch spines along them in a second pass:

I’ll probably do the long straight runs first, while waiting for the Montenegrin stitch book to arrive. I don’t particularly like the way I handled the bent spines and am hoping that Autopsy of the Montenegrin Stitch will help.

In other news, I spent the weekend knitting a hat. An outrageous black earflap cap, encrusted with a lime green crest. Bespoken, of course:

I started with Interweave Knits Army Girl Earflap cap – unisex despite its name (available in the IKE 7 Free Knitted Hats booklet). I added a bit more height just above the forehead, before the crown decreases because the recipient is a tall guy with a slightly longer head than average. I’m using Brown Sheep Lambs’ Pride Bulky. If you want to make this hat as published, one skein of it is more than enough for the whole thing. My green crest adds about half of a second skein, in that screaming color.

I’ve got some more of the ruff to add, then I have to snip it back, barbering it from floppy/sloppy to a uniform and threatening length. But all is on schedule for a hat-ETA of later this week.

MIXED STITCH INTERLACE

Another strip well started. This one is a mixed stitch interlace, graphed out from yet another museum artifact, and another pattern that will be appearing in TNCM2:

As my dawn-lighted picture reveals, I’m working it in two passes – first setting up the double running stitch outlines, then going back and filling in the dark center stripes. After some initial experimentation, I’ve settled on using Montenegrin stitch for those stripes. Although it’s a legitimate historical stitch contemporary with this style, and is spot on in terms of raised texture and density, I’m not entirely convinced that all artifacts labeled “punto spina pesce” use it (or in fact- employ the same stitch).

Contemporary work of that name more commonly refers to plain old long-armed cross stitch (LACS) but LACS doesn’t give the raised, tightly plaited appearance of the older pieces. Plaited – yes, but the angles in LACS are more acute than those in the museum artifacts. Montenegrin is closer in terms of texture, but is also not spot on. I’ll continue to experiment, but I will finish out this band using Montenegrin, and play further on later band.

To answer Ellen, this is done on 40 count using one strand of Soie d’Alger in color 1846. As you can see from the proportions of the work however, the ground is not exactly square. The 3×8 rectangles used to “bind” the interlaces together clearly show the skew. The bottom band of pulled thread work was done over units that are 4×4 threads. The double running band above it and the one I’m working now are done over 2×2 threads – approximately 20 stitches per inch.

To answer Rachel, yes – holding large frames is a pain. I much prefer working with my small round frame. But I don’t want to compromise the silk I’m using. I use my frame stand as that extra “third hand” to hold my frame, and then stitch with one hand above and one below it. If I can get a comfortable angle, it’s actually faster than stitching using the round frame, where one hand holds the frame and the other does all the work. The round frame does provide a more even tension in all directions. I suppose I could seam on a carrying cloth edge and then lace my piece left and right to improve side to side tension on the flat frame. I’ve done that before on others. But the Millennium provides much better overall tension than my old scroll frame, and I like being able to advance work at a whim, or collapse it for transport. I would not have been able to do this type of work on my old frame without lashing the sides.

To answer Anne, I don’t as a rule endorse retail outlets, I don’t accept recompense in money or kind for anything mentioned in String, and I don’t accept “review copies” or gifts from makers/sellers hoping for positive exposure. However I will say that the source for the frame was Needle Needs in the UK. I bought my silk from Needle in a Haystack in California, and the ultimate source of my ground cloth was Hand Dyed Fibers (I bought it from the original purchaser). The needlework stand I’m using is a Grip-It, which I bought about 20 years ago at The Yarn Shop in College Park, Maryland – long out of business. I altered the Grip-It to accommodate the Millennium by replacing the original jaw bolts with longer ones. It appears that the Grip-It is no longer being made.