INTO UNKNOWN SEAS – METHOD DESCRIPTION

A couple of people have sent me private notes asking about how I go about designing a larger project without graphing the entire thing. I attempt to answer, using the current Dizzy Grapes sideboard scarf/placemat as a possible approach.

It’s true I didn’t know how I was going to proceed when I began this project. I had a graph for the main field repeat, but only one iteration of the design, but not a chart for the entire area that design would inhabit. I didn’t have a border (yet). I had a piece of cloth of dubious cut and unknown count, and I had picked a thread well represented in my stash, with known easy-care laundry properties. I knew I wanted to make a large placemat type sideboard scarf, as big as attainable given the materials on hand.

The first thing to do was to figure out the largest possible area I could stitch on my unevenly hemmed ground. Leaving a bit of a margin around for easy hooping, I took plain old sewing thread and basted in a to-stitch area, with a bit of a margin. In doing this I discovered that the person who had reclaimed this bit of antique linen and done the crocheted edge treatments had a rather liberal interpretation of rectangles in general. Once my edges were basted in, I used simple measure/fold to determine the center lines, both north/south and east/west. Those were basted, too. Here’s that first step:

I also determined the thread count of this well washed, buttery soft vintage linen. It averages about 32 threads per inch, but is quite uneven, ranging from 28 to 34 in places, but didn’t dwell on that beyond satisfying myself that there was enough “real estate” inside my designated area to accommodate at least two full repeats of my chosen design across the narrow dimension.

Having the dead center of the piece determined, I chose a center point on the field design. I could have used the center of the smaller motif. That would probably have been easier, but I wanted the large rotating floral shapes to dominate instead of the largely unworked area surrounding the smaller motif. That was a bit tricky because the motif has a square unit in the dead-center, but I worked that straddling my basted center mark. Then I began working, snipping back my basted center guides as I went. (From here on the piece is shown rotated, with the narrow dimension north/south and the wide one east/west).

The shot above shows that first center motif in process, with the center guides being snipped back as the work encroached.

From there it was a simple matter of adding more floral motifs and the smaller X motifs they spiral around. Then after a group of four florals were complete, defining the space between them, centering the free-floating X in that area. Here are shots of those two processes. Note that as a Lazy Person, instead of tedious counting in from the established stitching, I used temporary basting to determine the centerpoint for the free-floating X motifs.

How did I know where to stop? No clue initially. I figured I’d get as close to the edge of my defined real estate as I could with full motifs, then pause to assess. It’s clear in the left photo that another full cycle of the repeat would not fit neatly between the established work and the basted guideline. But that area is also a bit wide to be entirely border. The proportions would be off. Plus that small X motif in the center bottom looks odd without at least a partial snippet of the floral motif spinning off its bottom leg.

So I did a rough count of the width left and decided I wanted a border that was about two inches wide at its widest (about 5 cm). Back to the drawing board to draft out something that complemented the design, and was somewhere around 30 units tall. I doodled up a couple of possibilities before settling on one. One strong consideration was the use of an inner line to contain the field pattern, so it had something even against which to truncate.

Once I had my border in hand, I decided that a bit of the center flower in its repeat could scallop below the basted edge line, so allowing for those 6 units, I counted up from my basted edge guide, and beginning at the center point I started the border of the first side. Then I worked right and left until I got to the edge of the “uncertainty zone” – the area as yet unworked at the left and right of the piece. Here’s the first side’s border in process.

As I established the border’s top edge (that field containment line), I went back to the main field, and worked the truncated snippet of the floral motif to fit. You can see that first snippet in the photo above.

Now on to that second side. But I had a cheat! Instead of starting it by counting down, I looked at that center floral snippet on the first side. Then I worked the floral snippet on the opposite side to the same point. That established the containment line on the second side, and I began the border at the center of the second side, working out to the left and right.

Now on to the ends. You can see now that I’m making these decisions on the fly. When I started I had no clear idea of what I was going to do beyond “Field. Border. Big.” I’m handling the problems and decisions as they are encountered, with minimal fretting about perfection along the way.

I chose to do butted borders on this piece. Neatly mitered, squared, or fudged border corners do exist on historical pieces, but they are in the minority. Even though my self-designed border isn’t particularly period representative (those repeating centered units with their own bounce repeat, as opposed to simple twigs all marching it the same direction), I wanted to use a non-mitered corner. I could have ended each off, designed a separate corner square, but I didn’t want to introduce another design variant – the border was already too busy.

Where to start that side border? What happens to the longer top and bottom borders? Do they just end or should I try to end at a visually logical place? Well, I chose the latter. I kept going on the bottom border to the right until I ended at the center of the bounce repeat. It’s just a few units shy of my designated basted edge. Not a lot of waste there. And knowing the height of the border, I established my north-south containment line.

You can see that I’m working on the first of the two spin-off floral sprigs along this side. When that’s done I will go to the centerpoint of the right hand edge and begin working the border from there, headed back to the corner shown. The side borders will end where they end. They will truncate oddly for sure, but having made the bottom and top congruent, what is on the sides, will be what it is. The side as a whole however should truncate in the same spot where it meets up to the border on the top. But no one is perfect. If it’s off by a unit or two, I will have accomplished the same degree of precision as most of the Ancients. They weren’t perfect either.

Stay tuned! The Grand Excitement of seeing the final product remains; and with it how things meet up, how close to symmetry I achieve, and how any as yet unknown problems are solved. And that’s before I decide how I’m going to edge and trim the piece out. Needle lace and/or a withdrawn/pulled element hem are both possibilities I haven’t yet ruled out.

So there you have it. Another adventure in bungee-jump stitching – starting a project with little or no detailed planning, no full project chart (just a partial chart showing the minimum needed), and no clear idea at outset on handling challenges encountered en route. I hope sharing this process inspires folk to take up their own self-composed projects.

BLACKWORK THREAD THICKNESS AND GROUNDS

I’ve recently had chats with several folk who ask about the number of threads they are supposed to be using when working linear blackwork (fills or the strapwork designs commonly done in double running or back stitch).

I attempt to answer, and the answer isn’t a plain, flat “always.”

There are several factors to consider for counted work. First there is the ground fabric. Some people favor purpose-wovens like Aida, Hardanger, Monks’ Cloth or Anna Cloth. These are made with large, prominent holes for easy counting. They come in a variety of stitch-per-inch (or cm) sizes. They range from 9 to around 22 stitch per inch (aka “count”). The more stitches per inch, the smaller those stitches are.

Other types of grounds are also used, with even weave (or near-even-weave) being less popular than the purpose-wovens. These grounds are flat tabby woven fabrics. They do not have a system of prominent holes for easy counting – to use them the stitcher counts the threads of the weave itself. Most sold specifically for embroidery are more or less true and square, with very close equivalent measurements of the threads running the length of the bolt (the warp), and across the bolt (the weft). The measurement of fineness of weave for these fabrics is expressed as threads-per-inch (or cm), and they can range from around 20 threads-per-inch (tpi) all the way up to 50 tpi or more. Stitchers generally work over a visualized square of 2×2 threads, so a 24 tpi piece of even weave would yield the same 12 stitches per inch as 12-count Aida, but the holes between the threads would be far smaller and less obvious.

Now aberrations exist. Not everyone works over 2×2 threads on even weave, and it is possible to work counted styles on anything you can actually see well enough to count, whether or not the warp thread count is even close to that of the weft. But in general, the ground cloth world splits into purpose-woven/larger more prominent holes; and (near) even weave/smaller, less evident holes.

On to thread.

It’s all over the map. The most common thread used today is standard 6-ply embroidery floss, but there are hundreds of other options. And even plain old embroidery floss is NOT uniform. Not even if they are of the same fiber. For example, DMC and Anchor cotton flosses have very slight differences in ply thickness, with the DMC (most of the time) being ever so slightly thicker than the Anchor. And even within a line, there can be variation because different colors take up dye differently, or because of visual impact of the color used (a dark thread will often appear heavier than one of a lighter color, even if there is no actual difference between them). And if you begin comparing across fiber types/spin types even more complications ensue – One ply of DMC cotton 6-ply is thicker than one ply of Au Ver a Soie six-ply silk, for example.

Here are three examples on even weave (please excuse me for not having Aida samples to hand – I don’t use it.)

First, here is an example of 32-count even weave linen (16 stitches per inch), worked with two strands of a six-ply silk – a small lot product produced by a boutique hand-dyer. Note that the individual stitches are about as thick as the ground cloth’s weave. They fill the holes into which they are stitched completely, and in fact are a bit jammed up into them, making intersections just a bit muddy and tight:

Here is that same ground, worked using just one ply of the same thread used in the previous sample.

You can see that the stitched thread is significantly thinner than the ground cloth’s weave, and that corners and angles are sharper. But the stitching thread still fills the holes, and doesn’t “rattle around” in them. There is another difference – the stitching doesn’t look as even. It’s harder to achieve a uniform appearance with skinny threads, but the difference that shows up in extreme close-up is less evident at normal viewing distance.

Which is better? It depends. One or two threads are both suitable for use with this fabric. Do I want a light and lacy effect? Do I want something darker and more strident? Should I accent the close, dense and angular aspect of a design (as on the left), or should I try to bring out the curves and delicacy (on the right)?

By contrast with these two balanced examples, there’s the piece I am working on right now. I am working the black bit with one strand of standard DMC 6-ply cotton floss. It’s about 14 stitches per inch (28 threads per inch).

Obviously the count on this stuff is skew. It’s not true even weave. Were it so the enmeshed ovals would present more like circles. But it’s close enough so stitched-it-will-be. Look closely at the size of the thread and the holes in the weave. Even though the black thread is slightly thinner than the fabric’s threads (like the lacy sample above) – look at it in comparison to the gaping holes between the fabric’s threads. It’s tiny and spindly. It’s lost. It wobbles. Corners are extremely difficult to keep square, angles are being pulled, and the threads that make up the design do not present in nearly as neat rows as the previous example. This same ground, with two plies of DMC? Much better looking:

In this case, I would advise AGAINST using this particular ground with only one ply of standard floss. It’s holes are too big. I’ll finish out my black interlace mask pieces, but I won’t be using a single on this stuff again.

And mixing thicknesses? It’s a great tool. Jack Robinson – the UK’s Blackwork Patron Saint (now of blessed memory) – was a strong advocate for both historical and modern pieces that mixed thread thicknesses.

Here are a couple of examples of doing so, from my own work. I find it of special use for giving modern-style voided pieces a lighter background touch, although I have also used it to de-emphasize veining inside particularly complex leaves on non-voided work.

First: In addition to using a different background pattern for each, the yellow ground on the left is done with one strand of DMC floss, and the yellow ground on the right, with two so you can see the density.

Second: Foreground and background in the same color, but the foreground is worked with two strands, and the background with one.

Now how does this work out on Aida? Again, I apologize for not having samples to hand. I don’t use it. The reason why I don’t is that I find the holes to be a visual distraction that take away from the presentation of the work as a whole. I’ve seen magnificent stitching on Aida, and I throw no shade on those who prefer it. But to me those holes can be way too big for the thread choices many people use. Like my wobbly sample above, the threads have too much play, and even tension without distortion at the corners or avoiding jaggy lines can be more difficult to control because the holes are big compared to the stitching thread.

For myself and my own work aesthetic, I prefer a well-stuffed hole (sometimes bordering on over-stuffed), and select my threads accordingly. One strand on Aida? I’d suggest two. Or three if it’s 12 or 14 count. But as in all things, my practice is not a yardstick by which you should measure your own preferences.

Look closely at your product. Try to understand why the threads behave as they do. Are you happy with your stitching? Think about your design goals. Even if you are interpreting a pattern by someone else there is plenty of scope in there for your own design choices. Thread thickness and proportion to the ground and to the size of the holes are just more variables you can play with to make any piece visually distinctive and uniquely yours.

Remember my family’s latke rules. Every family’s latkes are different, and every family’s latkes are the best. The same goes for stitching.

PROOFING

And we march around the perimeter, making skeleton after skeleton.

I’m just shy of half-way now, and I had to extend a tendril out to that point to make sure that I’m hitting my center mark. And I did!

As you can see comparing the blue line on the photo and the red line on the snippet of my chart, I’m spot on for alignment – not even a thread left or right of my center line.

One question I keep getting is how I maintain my location and ensure everything is in the correct spot without pre-gridding my work (without basting in an extensive set of guidelines to establish larger 10 (or 20) unit location aid across the entire groundcloth). I generally reply, “By proofing against established work,” but that then generates the second question. “How?”

So I attempt to answer.

For the most part I almost never work on fully charted out projects, with every stitch of the piece carefully plotted in beforehand. I compose my own pieces rather than working kits or charts done by others, and as a result I never have a full every-stitch representation as my model. My working method is to define center lines (and sometimes edge boundaries), but I pick strips or fills on the fly, starting them from my established centers, and working from smaller charts that are specific to the particular motif or fill that’s on deck. However, if lettering is involved I am more likely to graph that part out to completion prior to stitching, to ensure good letter and line spacing. (Leading, spacing, and kerning are close to my heart both as someone whose day job deals in documents, and as a printer’s granddaughter.)

For this project I DID prepare a full graph to ensure the centered placement of my very prominent text motto against the frame. I also wanted to miter the corners of the frame (reflect on a 45-degree angle) rather than work strips that butt up against each other, AND I wanted the skeleton repeat to work out perfectly on all four legs of the frame. To do that I had to plan ahead more than I usually do. (Note that the repeat frequency of the accompanying smaller edgings are different from the skeleton strip, so I also had to “fudge” center treatments for them so they would mirror neatly – another reason to graph the entire project).

But even with a full project graph available against which work, I didn’t grid – I worked as I always do, relying on entirely on close proofing as I go along.

The first step is a “know your weaknesses” compensation. To make sure I am on target I almost never extend a single long line ahead of myself, especially not on the diagonal because I make the majority of my mistakes miscounting a long diagonal. Instead I try to grow slowly, never stitching very far away from established bits, so I can make these checks as I work:

- Does the stitching of my new bit align both vertically and horizontally with the prior work? Am I off by as little as one thread? Am I true to grid?

- Is my new bit in the right place? Does the placement of the design element align with what’s been stitched before? For example, in this case, is do the toes of the mirror imaged bois back to back to the pomegranates match in placement in relation to each other and to the bottom of the pomegranate’s leaves?

Are my motifs in the right place?

- Am I working properly to pattern? It doesn’t matter if I am using a small snippet with just the strip design or fill that’s being stitched, a full project chart, or (as I am now) using prior stitching as my pattern – copying what’s been laid down on the cloth. Am I true to my design as depicted?

(Note the compression due to uneven thread count of the fabric.)

As I work, I constantly proof in these three ways – checking to make sure that my work is true. And if I discover a problem, I trace back to see where I went wrong, and I ruthlessly eliminate the mistake. For the record – there’s nothing to be gained by letting off-count stand in the hope of compensating later. Trust me – you’ll forget, mistakes will compound on mistakes, and you’ll end up wasting even more time, thread, and psychic energy on the eventual fix.

I hope this explains what I mean by proofing as you go. I know for most of the readers here, this will be second nature, and they won’t have thought of it as a disciplined approach, but for newer stitchers the old maxim “Trust but verify” should become a mantra. Verify, verify, verify. The sanity you save will be your own.

Finally, for Felice, who doubted I was using double running stitch for such a complex project in spite of the in process photos that showed the dashes of half-completed passes, here’s the reverse.

Yes, I do use knots for work with backs that won’t be seen, but I do it carefully so that the knots don’t pull through. Point and laugh if you must, but I reserve the right to ignore you.

DANCING AROUND THE CORNER

Having gone on and on about straight repeats as my bony bois march across the top of my piece, we have now come to the first corner.

Thankfully, my count is spot-on and everything is in place.

But why did I start with the strip of skeletons doomed to dance upside down? Because I knew that I would probably make some tiny adjustments to the design as I went along. The viewer’s eye is drawn to the closest point of the work, and the most logical part – that’s always the strip across the bottom, where the motifs are all right-side-up.

It’s unlikely that any small tweaks would be noticeable in the upside-down part at the top. So being too lazy (and waaay too short of thread I can’t replenish) I started there, knowing that I would not be ripping back vast regions to norm those tweaks.

Closer up, in a more normal orientation:

My last post discussed the non-historical use of the same framing element on either side of a mirrored repeat with horizontal directionality. Here’s another feature of this strip that’s not often seen in museum artifacts – the mitered corner.

The majority of corner treatments in surviving historical fragments have butted-up or improvised corners. Carefully plotted mirror images across a diagonal (mitering) are quite hard to find. But I decided to do one anyway. You can spot the diagonal running through the center line of the rightmost internal knot, down through some leafy bits, and into a flower-like shape. I’ve also established the beginning of the 90-degree flipped border, with the upper part of that skeleton plus the first pomegranate underway.

I’ve also rounded the outside corner. In a serendipitous happenstance (I can’t claim I planned it ahead of time), the width and height counts of my marching plumes are equal, so I was able to fudge the corner with one last plume on a long stem.

Side note: At this point I really don’t need to refer to my printed pattern any more, I am mostly working off prior stitching, with occasional glances back at my chart to make sure all is aligned and true.

But that inside edging – it’s different. I’ve introduced another element, playing with the eternity knots and tying them into the plume strip. I did this because the thread count of the warp (the threads that stretch up-down in the detail photo) is denser than the thread count of the weft (those that go across in the detail photo). The closer together the threads are, the more compressed the design will be in that direction. My skeletons marching up/down the sides of my piece will end up looking ever so slightly shorter and chunkier compared to their more lanky brothers that tumble across the top and bottom. BUT I can draw the eye away from that difference by adding the additional knotwork strip.

So it turns out that my design is all about insouciance, breaking historical composition precepts, and visual deception. Still for all of that I think that its look is more closely aligned to the aesthetic of historical blackwork rather than more modern pieces. Just my opinion, feel free to differ.

Class Handout Page

And for having the patience to read down this far, here’s another present. I was going through some older files and came across this class handout page. I’ve taught several workshops using it. The last one I came equipped to do was for a public SCA demo in Rhode Island, although the circumstances and attendees made just sitting and chatting about the stitching a better option. Still, I did update the handout, and it may as well be of use to someone.

The patterns are (more or less) ordered in level of complexity, and are intended to be a self-tutorial in double running stitch. When I teach I provide the page below, a strip of Monk’s cloth and length of standard embroidery floss and needle, plus an inexpensive hand hoop (if I have some to spare). Depending on prior experience, stitching proficiency, confidence level I encourage the participant to select one of the designs from the leftmost two columns, to try out face-to-face in the workshop. Then I encourage everyone to use the rest for self-study at home.

For self study, what I suggest is to just grab a piece of cloth and begin – no need to plan an intense, composed sampler. Pick a point anywhere on your chosen ground, then starting at the spot in the upper left column where you feel comfortable, continue down that column to the simple acorns. Then keep going. The next design in the complexity sequence is the flower spring at the top of the next column. Go down that column to the folded ribbons.

After that, I’d suggest attempting the birds at the bottom left. From there the vertical star flowers, then the knots, four-petal flower meander, and the design immediately above the title. Once you’ve done all that the remaining four intermediate patterns on the page should be well within your grasp (the heart flower all-over, fancy acorns, geometric strip, and oddly sprouting peppermint-stick squash blossoms).

Of course you can be totally random and just use these designs as you will. No need to march in lock step with the protocol, above.

Download this handout in PDF format from my Embroidery Patterns page. It’s the last one listed (click on the thumbnail there to get it, then save it locally).

As ever, if you stitch up something from any of my designs, please feel free to send pix. I always get a big smile out of seeing you having fun with the pattern children. And if you specifically say so and give permission to re-use your photo, I will be happy to post it here and index it under “Gallery”.

BOOKMAKING 108: RIPPING OUT AND RECOVERY

The last post of mea culpa probably left people wondering how it was going to all turn out. Here’s the result:

I only needed to tease out one straight line of stitching – the former rightmost edge of the previous side. Now the two borders join to make one larger mirrored strip that takes up the spine area and wraps around to be visible on the front and back. Not as I originally planned, but acceptable.

And I have been able to keep going on the second side, working my double leaves in red, and the diamond fill ground in yellow. Again, not as originally planned – the repeats will not be neatly centered left/right, but because this particular fill is eccentric, I bet it won’t be noticed by anyone who isn’t aware of the problem in the first place. (Mom, avert your eyes).

Now on to today’s submitted question:

How do you rip back?

With great care.

It’s very easy to inadvertently snip the ground cloth, and that’s a tragedy when it happens. But I have some tools that help.

The first thing is a pair of small embroidery scissors with a blunted tip. These are the latest addition to my ever growing Scissors Stable, and a recent holiday gift from The Resident Male. Note that one leg has a bump on it at the tip. That’s the side that is slid under the errant stitch being removed, to make the first snip. Although these are sharp all the way to the tip, the bump helps prevent accidentally scooping up and nipping the ground cloth threads.

To rip back taking all due care, I snip a couple of stitches on the FRONT of the work. Then I employ a laying tool and a pair of fine point tweezers for thread removal. The laying tool was also a gift from The Resident Male, and replaces a procession of thick yarn needles I used before I had it. My tool is about 3 inches long (about 7.6 cm).

My pair of tweezers is one intended for use in an electronics lab. I found it in the parking lot of a former job, probably dropped by someone testing robots in the back lot. I tried to return it, flogging it around to likely techfolk for several months, but had no takers. Seeing it was to remain an orphan, I adopted it into a new fiber-filled life. I love it. It’s wicked pointy, and even with the dented end (probably damaged when it fell off the test cart onto pavement), does a great job of removing tiny thread bits.

Having snipped the threads on the front, I use the laying tool’s point (augmented by the tweezers) to tease out the stitches in the reverse order they were worked, doing it from the back. Luckily this style of work has a logical order and it’s usually pretty easy to figure that out. But in some cases it gets harder. When that happens, it’s another judicious snip on the front, followed by use of the tweezers from behind to remove the thread ends for discard. (While I can sometimes recover/reuse a live thread after I catch a mistake of a few stitches, in general if the run is long, or I’ve ended off the strand there’s little point in trying to save it and stitch with the now-used and damaged/fuzzy piece of thread.)

If the color is in the least bit friable and liable to crock on the ground fabric, I cut more and pull less – making sure to remove all threads from the back rather than pull them forward to the front. This minimizes color/fuzz shed on the front, public side of the work.

If any snipping needs to be done on the back, flat and parallel to the ground, I pull out another resident of my Scissors Stable – a pair of snips I bought at the SCA Birka marketplace event, two years ago. They look like this:

These were a great buy. Inexpensive, super-sharp (I think the snipping action helps keep them sharp), and because they are not held like finger-hole scissors, very easy to manipulate to snip close and flat to a surface.

And what to do if there are fuzzy bits or surface discolorations that remain on the front? Here’s my last resort. I wrote about it before:

Yes. Silly Putty. I have found that a couple of gentle blots will pick up fuzz and shed bits of color. The trick is NOT to scrub, just support the cloth from the back (I use the top of the stuff’s eggshell container), and press the putty gently onto the affected area – then remove it vertically and quickly. Make sure not to let it dwell on the surface.

I will caution that there is risk doing this. I have no way of knowing if anything exuded by Silly Putty will be a life-limiting factor for the threads or ground in 50 years – if discoloration or other complications might ensue. But the Materials Safety Data Sheet for it doesn’t turn up anything particularly evil, and I am willing to risk it. You will have to make that decision for yourself on your own. Having warned you I take no responsibility if it ends up doing so.

ALTERNATIVE ALPHABET RESOURCES FOR INCLUSIVE STITCHERY

Lately I’ve seen a couple of resources for embroiderers who wish to make samplers or other stitchings to honor friends or family who are differently-abled. I post them here for general reference. [NOTE – THE LINKS BELOW WERE EDITED ON 22 AUGUST 2022, AFTER I LEARNED THAT MR. TAKAHASHI’S WEBSITE IS DOWN.]

First is this alphabet from type designer Kosuke Takahashi. It takes a linear construction alphabet, and overlays Braille dots on it, to form a construction that can be read by those familiar with both type forms.

Sadly, Mr. Takahashi’s website appears to be down, but the article about his invention along with a better visual of the material above can be found here, on Colossal. The author’s old site noted that his workis free for personal use. If you want to compose an item or design for sale, you would need to contact the designer to license the font.

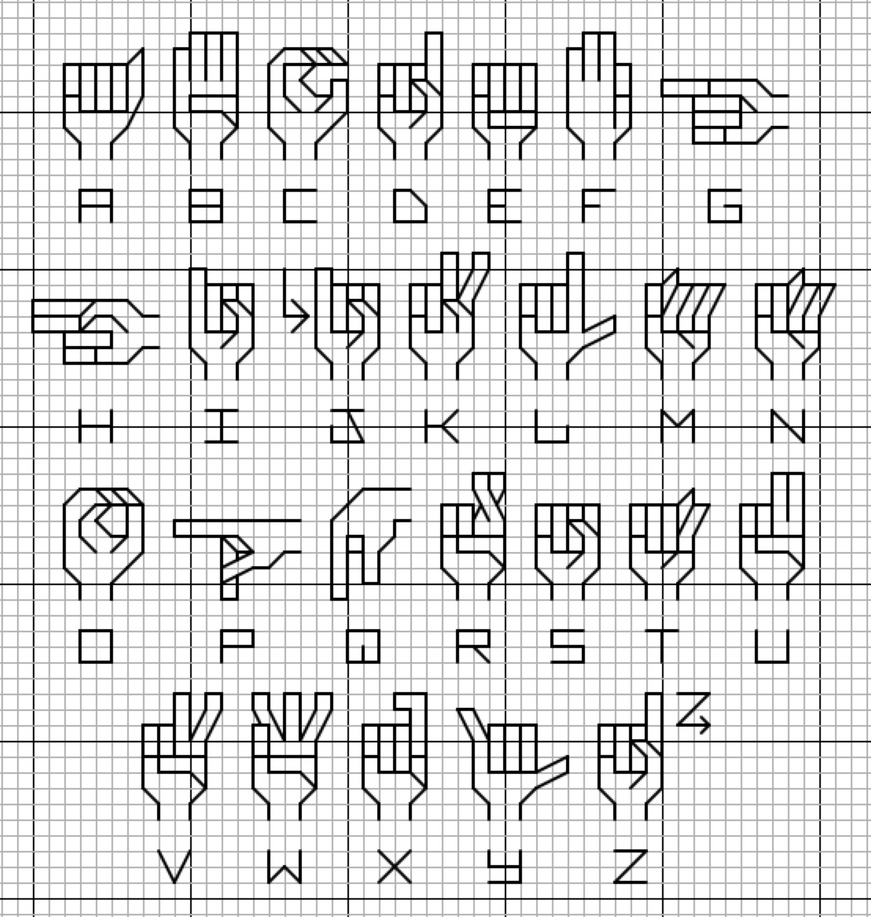

Second is a linear stitch interpretation of the sign language alphabet.

The source is Deviant Art board poster and cross stitch designer lpanne, and is under her copyright. Again, if you create anything from this for sale, please take the time to contact the artist and ask for permission.

Although this last item presents text in a non-standard way, for most of us it makes it less rather than more comprehensible. But it’s a nifty idea for the nerdy-minded among us. Artist Sam Meech knits up scarves using ASCII coding, represented by two colors (one for 1 and the other for 0). He’s able to include entire quotations and text passages in his Binary Scarves. He sells them at his site below.

(photo shamelessly lifted from Sam’s site)

You can read more about Sam’s scarves here.

If you want to create your own binary string, tons of text-encoders abound. I used this one to translate

STRING-OR-NOTHING

into

01010011 01110100 01110010 01101001 01101110 01100111 00101101 01101111 01110010 00101101 01001110 01101111 01110100 01101000 01101001 01101110 01100111 00001101 00001010

If this is new to you – each eight digit “word” is in fact a letter. “N” for example is 01101110. The binary scarves work like early paper punch tape, stacking each octet one above another. So the word “STRING” would come out like this:

01010011 = S

01110100 = T

01110010 = R

01101001 = I

01101110 = N

01100111 = G

There was a time in my distant past that I used paper tape, and could recognize and read the octet patterns by sight. But that was long ago, in a technology forgotten by time…

DOUBLE RUNNING STITCH LOGIC 104 – A REVIEW

Based on private notes of inquiry and discussions on various historical needlework-related boards and forums of late, I see that people are still confused about the working logic of linear stitching. In specific, how to determine if a design can be worked entirely two-sided.

First off – the two most popular historical methods for working thin linear designs are double running stitch and back stitch. The big difference between the two is the appearance of the reverse. Done meticulously, with care paid to invisibly terminating threads, double running stitch is almost indistinguishable front and back. Almost because a few people do produce a slight difference due to differential thread tension on each of the two passes required to produce a unbroken line, but that difference mostly settles out over time. Back stitch on the other hand produces a public side very much like double running, but the reverse of the work is heaver, and depending on the stitcher can look like outline or stem stitch, or even like a split or chain stitch if the needle pierces the previous stitch as a new one is made. Of necessity in back stitch there is twice as much thread on the back of the work as there is on the front.

|

|

|

Double Running. |

Back Stitch. |

Double running stitch takes two passes to accomplish because it first lays down a dashed line, with the spaces between the dashes being filled in on the second pass. A back stitch line is completed in one pass, with no need to revisit areas previously stitched to complete the line.

Many people prefer back stitch because there IS no going back. They like the certainty of knowing exactly where they are at all times, over the pretzel logic of calculating how not to be caught in a cul de sac while retracing steps in double running. Personally, I prefer double running, and follow double running logic even if the piece I am working will not be seen on both sides. I find that path planning to be fun, and I appreciate thread economy, especially when working with more costly or difficult to source hand-dyed silks.

But for some one challenge of double running is knowing which designs can be worked in that stitch such that both sides can be made totally identical.

It’s easy. Any design that has no “floating elements” is a prime candidate. If true double sided is a total goal (including invisible termination of thread ends), any piece that has a floating element large enough to allow that burial is also a possibility. It doesn’t matter how complex a design is, so long as elements are all branches and detours off of one or more main baselines, they can be stitched double sided. And yes – there CAN be more than one baseline in a design. More on baseline identification is here. The logic of following detours and returning to the baseline is here. How to break up a large design into several smaller baselines is here.

Identifying floating elements

That’s easy. They are any ornament or detail that is discontinuous from the main line of the design.

Here are several that I’ve done in double running, based on one or more continuous baselines, with no floating element deviations. In these designs every part of every work is attached to every other part, at one or more points.

The last one has additional embellishment in long-armed cross stitch, and the final one includes two edge borders, each done as their own “line” separate from the main motif.

By contrast, here are several that have those “floating elements” called out.

The knot element in the all-over at left is not attached to the main pomegranate frame. It is however just large enough manage thread-end-hiding. So while its presence makes this a tedious and difficult pattern for double-sided double running stitch, it is not a deal breaker. However those little accent diamonds are deal breakers. Too small to hide the ends, and detached from the main design. The ladder element in the arms of the repeat at right is broken from the main design, and is too small for end-camouflage.

There are often short lines or sneaky little floating accents hidden in both simple and more complex repeats. Strawberry pips are notorious for this, although I haven’t any stitched examples to hand:

My dragonbeast, however lovely, has quite a few floating elements, making him a problematic choice for a fully double-sided work. (Eyes and faces are almost always difficult).

And this bit, stitched from a Lipperheide book, is the absolute poster child for discontinuity. I didn’t mark them all, but you get the idea. The spaniel and possibly that center bundle thing are the only bits large enough in which to bury the ends, if a fully two-sided result is desired.

Here’s a tricky one. Look closely at the bit on the left.

It looks continuous, but it’s not. There are in fact FOUR separate double-running baselines, AND a discontinuous element in the motif. He’s in the red circle on the right. Like the round knot in the first example this might be done double sided, provided that the stitcher was willing to terminate separate ends for that relatively large floating element.

So in short – it doesn’t matter how complex a design is, so long as all elements are continuous it CAN be stitched fully double sided, in double running stitch.

ASSORTED BLACKWORK HINTS

I’ve gotten lots of questions about blackwork, my methods, and products over the years. Some more than once. I’ll try to round some up and answer them here, for ease of reference. Feel free to post more in the comments, and if I have useful advice, I’ll answer them at a later date.

It looks so perfect! Do you make mistakes?

Lots. Continually. Sometimes at the same place in a design repeat, again and again. But for the most part, I carefully pick them out, using my needle tip, a really good pair of sharp tweezers, and if needed, something sticky (like blue painters’ tape) to tidy up any remaining surface fibers.

I find that clipping a few key stitches on the front, then withdrawing the snippets from the back leaves the front of the work a bit neater, than does doing all of the removal from the front.

Do you stitch guidelines to help with counting?

No, I don’t. Or not in the way the asker probably means. I don’t establish a grid over my entire ground cloth, but I do usually run a basting thread (but not in specific count) along the extreme edges of my stitching area, and at the center (both laterally and longitudinally), so I know where my margins and center are. For example, as I began my forehead cloth, you can see the line below the growing stitching that marks the boundary of my work (in this case, instead of stitching directly up to it, I decided to stitch no closer than three units of it); plus the diagonal that bisects the established bit. That line marks the center.

Sometimes on larger projects I might mark lines that divide my ground into quarters or thirds, too. It depends on the size of the project and what I am doing with it.

One thing to note – I have never stitched from a fully complete graph that shows the entire project. Yes, I know I published one here, but I am a “bungee jump stitcher” and more often than not, pick my patterns on the fly. The exception is of course, lettering. I do graph out my words or phrases, to work out problems in word or letter spacing, or to find the center of the motto (if I want the motto centered when stitched).

Then how do you keep things aligned?

I start from the center, as seen above, then work either right or left until I get to my desired width. Since most of my work is either a straight, or left-right or up-down mirror image or bounce repeat, I then go back and fill out the strip or pattern in the other direction, taking care to end at the same point in the repeat as the first edge.

Do you ever draw in or otherwise mark your designs?

Yes, but mostly for inhabited blackwork, not strapwork. Inhabited blackwork is the “outlines plus fillings” subtype. Strapwork is the substyle that produces long bands often used to edge household linens or garments.

I’ve used a couple of methods to establish outlines for fills. First, there’s simple drawing. Here, I’ve taped my line drawing to a window, with the ground cloth on top, prior to tracing the design onto the cloth using a pencil. You can just barely make out the outlines in the in-process shot.

And here I have established my design on the count, using small cross stitches to create the outlines for the shapes to be filled in. I finished off those heavy lines by overworking them with a nice, solid chain stitch because I wanted prominent outlines. I could have basted or done a lighter line of stitching instead. I’ve done that to make pounced chalk less transient, but I don’t have photos of in process works that employed chalk plus basting.

Do you ever work in multicolor?

Sure. Lots. Here are a few. Starting at the left top: From 1973, in high school, prior to my involvement in the SCA – a happy mash-up of sampler bands, still unfinished; small stitched Moleskine type notebooks covers done as an East Kingdom largesse donation in 2012 (I wonder if they ever were received, and to whom they were given); a band sampler as engagement present circa 1985 or so, for a friend whose wedding plans expired prior to completion of the sampler, which explains that one still being unfinished; the Trifles sampler, done about a year ago, as a perpetual nag for Younger Daughter to take with her to college; and the Permissions sampler done as a present for our Denizen, the same year.

Stitching Equipment Tips?

These recommendations are specific to the way I work. But my comfort level is not the same as everyone else’s, so if you do it differently, you are not wrong.

A frame helps. Preferably a hands-free frame. I like stiff tension on my stitching ground, so I prefer a nice, tight frame. But I stitch the fastest with one hand over and one hand below my work, so I am happiest with one that doesn’t require me to grow a third hand to hold it. My faves are my Millennium flat scrolling frame, held securely in my ancient Grip-It stand (I had to replace the bolts of the original to accommodate the Millennium’s thickness), and the Hardwicke Manor sit-upon round frame.

If I am using a round frame, hand held or sit-on I ALWAYS pad at least one of the hoops with twill tape, stitched securely down on the hoop’s inside. This increases grip, and protects stitches that are “hooped over” after they are laid down.

Since I am usually working on the count on relatively fine grounds (I prefer 32+ threads per inch, with 38-42 being my sweet spot, and 50+ just to show off), my stitches are usually short and not prone to damage from a round hoop. But if there is any doubt at all, I haul out the big boy and work flat.

Needle choice can avoid headaches. For this sort of work you want a blunt tip needle to avoid splitting ground cloth threads. You want the needle to glide between them and not force them, to avoid disarranging the ground threads more than needed to accommodate passage of the stitching thread. Many people use tapestry blunts, but for the gauges I work with, often with just one or two strands of floss or thread, I find the large holes in tapestry blunts to be annoying. The threads slip out all too easily. So instead I use these ball-point needles, intended for hand sewing on polyester knits. They are relatively easy to find in sewing stores where they are usually grouped with the regular (not embroidery) needles.

Wax. This is a love-it or hate-it issue. I love it. I almost always run my thread through beeswax prior to stitching. It strengthens threads, avoids fuzz and shedding, makes threading and maintaining even thread feed on multi-ply floss better, and makes them glide through the ground. Yes, even silk. Since my chosen style of stitching uses extremely short stitches, the sheen of silk over a long run (like in satin stitch) is minimal at best. If I think that the wax will have an effect on the final product, I may only do it lightly, or restrict waxing to the final two inches that will be threaded through the needle, but I still do it. I keep one lump of beeswax for light color threads, one for darker colors, and one for black. Threads do shed or crock onto the wax, and using several little blocks keeps the lighter colors clean. And it must be beeswax. Candle wax doesn’t have the same properties, and can stain.

Double sided?

Rarely. It’s a noble party trick, and useful for handkerchiefs, cuffs or collars viewed from both sides, but even historically, not always done. There are paintings that show different stitching patterns on the inside and outside of a collar band.

BUT

I do tend to use double-sided logic for most, but not all of my linear stitching. I find it saves thread, and I prefer the look and feel of the finished product. I’ve done some tutorials on how to determine baselines and stitching order (read from bottom up). I also confess to abject heresy if my pathing needs the jump and the final presentation form allows it.

Most designs have several possible stitching paths. Which one I take can vary from repeat to repeat, depending on how much thread I have left on my needle, where I am headed after the current bit, or even plain old experimentation. The path planning for me is very relaxing, and I rarely get lost or paint myself into a corner because I use tricks to idiot proof my path (being the biggest idiot stitching on my work at any time).

Tricks???

Yes. Here are some rules. All are occasionally broken, but for the most part they govern my path planning:

- Never go off on a long limb, establishing a very long line of stitching that branches off the main work. 90% of the mistakes I make fall out from this, especially if lots of diagonals are involved. I prefer to proof my work, by trying to do it by section adjacent to or in line with prior work. I constantly refer back to the established stitching to make sure I am not off count.

- There’s no reason to fret about having enough thread to make the return journey. Many people stitch double running out in one direction until half their thread is used, then do the second pass, filling in the remaining stitches on their way back to the starting point. But they often run out and have a section left over to complete using a second thread. Instead of there-and-back-again, I head out in one direction, taking all detours, until my thread is used up, then rethread the needle and start again from the beginning point to fill in the every-other stitches. And (gasp) there’s no shame in using TWO THREADED NEEDLES, leapfrogging yourself an inch at a time if that helps you keep your place.

- In general it’s preferable to take every detour as it is passed, especially if it’s a branching dead-end. If I run out of thread during a detour, I pick up again from that point and complete the detour to return to the baseline, rather than starting the next pass from the baseline itself. That way I don’t get stuck in cul de sacs.

- If there’s a joining that you don’t want to take as a detour, and it hooks up to the main design elsewhere (it’s not a branching dead end), it’s a good idea to work a stitch or two out on it, so there’s an attachment twig. When you come by later from the other direction, it’s lots easier to align with that twig than it is to judge proper place against an unbroken baseline.

- Those little spikes and shading lines that radiate from a baseline in the more complex designs are your friends. They make counting much easier. Work them on the first pass and use them as part of the proofing process.

- If you are using an even number of floss strands and thread grain isn’t a problem (and for most of short-stitch linear work, it isn’t) minimize knots by cutting your length twice as long as you need, folding it in half and waxing all but the loop just formed, and on the first stitch, catching the loop made to secure your end.

- If you are using an odd number of strands, or thread grain is an issue, and you don’t want to make a waste knot (which I rarely do for this kind of work), make a secure knot at the end of your thread, then use your needle to pierce the strand just below it, catching the thread in the same manner as #6 above. Your knot will be secured and will not pull through to the presentation side.

- Stitching over 2×2 threads is easiest. 3×3 and 4×4 are also doable, but look better on grounds that are at least 40 threads per inch. You can tame a skew ground – like a piece of inexpensive linen or linen look alike NOT sold as even weave – by stitching over an uneven count. If for example, your ground has more stitches north-south than east-west you might stitch over 3 threads in the north-south direction, but 2 in the east-west direction. This does make a project more exacting, and I don’t recommend it for someone who is just learning stitching logic.

More questions? Ask away!

FOREHEAD CLOTH/KERCHIEF PROGRESS

This is working up to be a quick stitch:

I attempt to answer questions submitted via email and on-line. If you have other questions, please feel free to post and ask. There are no secrets here.

Where/what is this pattern?

It’s one of the many designs in T2CM. It’s quasi-original, based on a 15th century strip pattern from my all time fave V&A sampler, the famous (and infamous) T.14.1931. I presented the strip in TNCM, but here have morphed it into an all-over. There are only two designs in T2CM that revisit some aspect of a pattern from the first book. This happens to be one of them.

Here is the original historical design in strip form, as worked on my Clarke’s Law sampler:

What stitch are you using?

Mostly double running, with short hops in “Heresy Stitch”. But I’m not being slavish about the double-sided/double running protocol. I am using knots, and I am strongly considering a muslin lining for my forehead cloth. I think it will help it wear better, by reducing stress on the ground fabric. Therefore, with the back well hidden, I am under no pressure to do a perfect double-sided parlor trick. That being said, I do tend to stick to double sided logic for best thread economy and minimal show-through.

What thread and ground are you using?

The ground isn’t fancy – it’s a prepackaged linen or linen blend even weave, with a relatively coarse thread count of 32 threads per inch. It is stash-aged, and parted company from the packaging long ago, so I am not sure of the brand name it was marketed under, or the retail source. I’m stitching over two threads, so that’s about 16 stitches per inch. I tried stitching over three, but thought the look was too leggy.

I am using a special treat thread – a small batch hand-dyed silk from an SCA merchant. I got it at Birka, and I hear it will be intermittently available at the Golden Schelle Etsy shop*. The thread is dyed with iron, tannin, and logwood, and is a warm black in color. In thickness it is roughly equivalent to two plies of standard Au Ver A Soie D’Alger silk, although it is not a thread that can be separated into plies.

Do you wax your thread?

Yes. For double running stitch work, even in silk, I wax my thread lightly with beeswax; paying special attention to the last inch for threading through the needle. While I would not as a rule wax the entire length of the silk for work that depends on sheen (like satin stitch), at the very short stitch lengths used in double running, loss of sheen is minimal. Waxing keeps the thread from fuzzing against itself as it is pulled through the same hole more than once, and (if you are working with multiple strands) minimizes the differential feed problem, without resorting to using a laying tool – which I find tedious for such short stitch lengths. Others adore laying tools, so use of them is a matter of personal preference.

What needles do you use?

I favor a rather unorthodox choice for single strand double running – ball point needles intended for hand sewing on tricots and fine knits. They have a nice, rounded point, that slides neatly between the threads of my ground fabric, and a small eye. Blunt pointed needles intended for embroidery often have large eyes, which make thread management for a single strand unwieldy, allowing it to slip out of the eye too readily.

How do you know when to “go back again” in double running?

A lot of people think that working double running means you head in one direction, then turn back and retrace your steps. They carefully calculate the length of their stitching thread, and when they get to the half-consumed point, turn around and go back. This works, but tends to cluster thread ends. If you cluster your ends you end up with (for double-sided work) a large number of ends to hide in a very small space, or (for single sided, with knots) an untidy zone, with many knots and ends in the same place, which can show through to the front.

Instead I just keep going. I use up my length of thread, following my stitching logic, headed in one direction. Then I begin a second strand,staggering my starting point from my original start, first filling in the previously stitched path, and then extending the design further. Since I tend to do offshoots and digressions as I come to them and these do eat more thread as I trace them out from and then back to my main stitching line, I rarely have more than two ends at any one point in my work, and those two-end spots are widely distributed, rather than clustering in one small area.

How do you determine the baseline and stitching logic in an all-over?

There’s a little bit of catch-as-catch-can, but the basic concept is dividing the work into zones. In this piece the zone is flexible, and can be centered on either square area bordered by the spider flowers, connected by the twisted framing mechanism; or on the smaller area defined by the “root zone” of those spider flowers, again connected by the twisted framing. I go around either one of those, hopping between them as needed. In either case, the small center elements – the tiny quad flower, or the quad flower with the elongated tendrils, is worked separately, with no jumps back to the main motif.

And speaking of that tendril-flower – I am not entirely happy with it. I may pick it out and draft something else to go there. For the record, the nice, large square it inhabits would make a nifty place for initials, heraldic badges, whimsical creatures, original motifs, or other personal signifiers.

Why are you using a round frame?

Because I have two flat frames and one round (tambour) sit-on frame, in addition to several round in-hand hoops. I have works in progress on both flat frames, and don’t want to dismount them to do this quickie. My tambour frame has a padded bottom hoop, and when time comes to move the fabric and squash bits of just-done embroidery, I will pad the work with some muslin to protect it on the top as well as the bottom side. Again, working short stitches with no raised areas – even in silk – makes this a less risky proposition than it would be for other stitching styles.

Can I see the back?

In the next progress post I’ll include a shot of the back.

* In the interest of full disclosure (and the no-secrets here thing), the un-named proprietor of Golden Schelle is my Stealth Apprentice. Shhh. It’s a secret.

![tweezers[1] tweezers[1]](https://kbsalazar.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/tweezers1_thumb.jpg)

![kerchief02[1] kerchief02[1]](https://kbsalazar.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/kerchief021_thumb.jpg)

![gane-3[1] gane-3[1]](https://kbsalazar.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/gane31_thumb.jpg)

![gane-2[1] gane-2[1]](https://kbsalazar.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/gane21_thumb.jpg)

![coifdetail[1] coifdetail[1]](https://kbsalazar.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/coifdetail1_thumb.jpg)

![misc-embroidery-3[1] misc-embroidery-3[1]](https://kbsalazar.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/miscembroidery31_thumb.jpg)

![book-cover-2[1] book-cover-2[1]](https://kbsalazar.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/bookcover21_thumb.jpg)

![strip[1] strip[1]](https://kbsalazar.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/strip1_thumb.jpg)

![trifles018[1] trifles018[1]](https://kbsalazar.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/trifles0181_thumb.jpg)

![permissions06[1] permissions06[1]](https://kbsalazar.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/permissions061_thumb.jpg)

![zrtn_003n181cb7c5_tn[1] zrtn_003n181cb7c5_tn[1]](https://kbsalazar.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/zrtn_003n181cb7c5_tn1_thumb.jpg)

![fannyframel[1] fannyframel[1]](https://kbsalazar.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/fannyframel1_thumb.jpg)

![hoop[1] hoop[1]](https://kbsalazar.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/hoop1_thumb.jpg)

![ball_points[1] ball_points[1]](https://kbsalazar.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/ball_points1_thumb.jpg)