BOOK FIND!

I have stumbled into an unusual object – well, a set of three, actually.

This is a set of the first edition German printing of Alexander Speltz’ Colored Ornament, printed in 1914, with text in English. It’s a three portfolio collection of full color plates, with an accompanying index/survey write-up for each portfolio. The thing is divided into Antiquities – mostly Greek and Roman, with a smattering of Pre-Columbian, plus some plates showing eastern Mediterranean art and decoration; Middle Ages – mostly Romanesque through Gothic, with some from Byzantium; and Modern – not particularly modern, it appears to cover early Renaissance up to pre-Empire.

Now before you hyperventilate and begin looking the thing up on the used book market, note that it is in extremely rough shape, and plates are missing. The Antiquities and Modern folios are each missing 4 or so, and the Middle Ages folio is missing about 10. The folio covers are crumbling, and the heavy paper to which each image is affixed is well on the march to being dust. It’s clear that someone cherry-picked pages to frame separately. In fact, the person I got this from said he was doing exactly that. Still, there’s plenty of good material here, and I do have the companion about/index volumes. And it was free.

Here’s a small sample of the roughly 150 plates that remain:

This is a very “hard artisan” focused work. There are just a couple of plates featuring textiles. Only one with embroidery. It’s mostly architectural ornament, ceramics, jewelry and other metal work, calligraphy and early printing, some furniture, glass, mosaics, and interior ornamentation. Not sculpture, not weapons, not hanging paintings. Still there’s a wealth of inspiration here.

I intend to keep these survivors together and ward them as well as I can given that I’m not an archival museum. I see folk selling individual plates from the thing, but even at the prices they are asking I’m not tempted in the least to break it up further. Local pals, if you are interested, drop me a note. A gentle viewing and photography session would not be out of question.

WHEN IS MORE OF THE SAME NOT MORE OF THE SAME?

Another post that only a stitching history nerd will love.

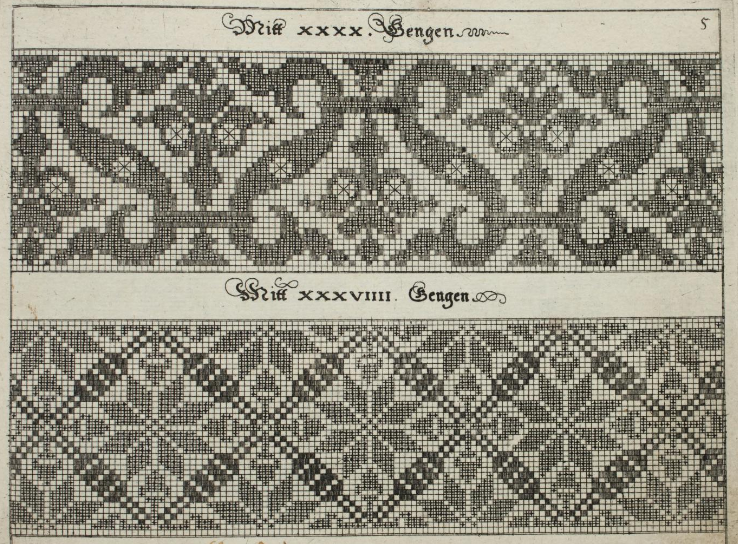

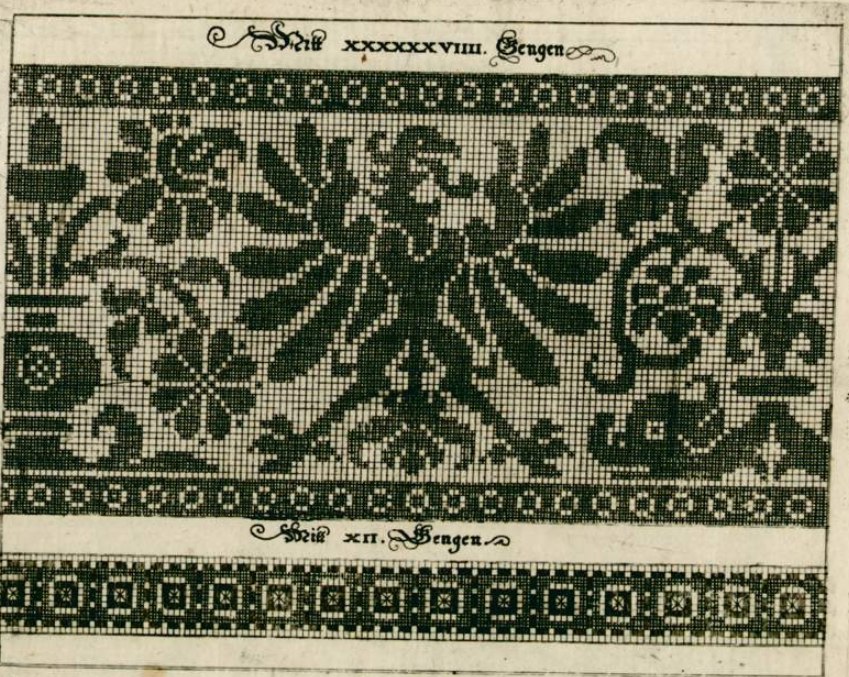

The last post explored some differences between modelbooks that looked like they featured the same patterns, but in fact were not printed from the same plate. This one looks at one of the most widely reprinted and well known modelbook authors – Johann Siebmacher, and three of his works, all available in on-line editions. All of the excerpts below are from these three sources:

- Schön Neues Modelbuch von allerley lustigen Mödeln naczunehen, zuwürcken unn zusticken, gemacht im Jar Ch. 1597, Nurmberg, 1597, – the source work for Mistress Kathryn Goodwyn’s Needlework Patterns from Renaissance Germany

- One reprinted in 1886 as Kreuzstich- Muster: 36 Tafeln des Ausgabe, 1604, that calls out Siebmacher as its author.

- One indexed simply as Newes Modelbuch with him as author, possibly 1611, but unclear from the source

Many of the designs in these books seem to repeat edition to edition. Some are unique to only one. Before we begin, it’s worth remembering that these books are survivals. Long use and reuse over decades have resulted in page loss. None of the editions are complete, as in “all intact in one original binding,” and some may have been re-composed at a later date from other partial works. But we do what we can with what we have, and Siebmacher’s editions have title pages in them, and distinctive numbering and framing conventions that can lead to a reasonable conclusion that they were from the same printing workshop.

All of the books show graphed designs suited for reproduction using several techniques, including various styles of voided work on the count, lacis (darned knotted net), and buratto (darned woven mesh). Twp of them also include patterns that would be suitable for other forms of lace. Over time these patterns went on to be executed in weaving, cross stitch, filet crochet, and knitting, too. The descendants of these designs ended up in multiple folk traditions and samplers on both sides of the Atlantic.

In addition to the longevity of their contents, Sibmachers books are among the earliest that seem to indicate execution of the design using more than one color or texture, a feature not common in the black-and-white printed early modelbooks. Here are examples the first two books. But I don’t think that these pages were originally printed two-tone. I think they were hand-colored to add the darker squares, either at the time of manufacture or later.

| 1597 | The possibly 1611 edition |

|

|

Obviously, the two samples above were printed from the same block. But the pattern of the darker squares is different, and if you look closely, the some of the solid squares looked colored in, as opposed to having been originally printed that way. I can say the retoucher who did the 1597 was a bit neater. I don’t think these were colored by the book buyer, because every single edition of Siebmacher’s works that I’ve seen have included multi-tone pages like this.

Here are other single- and multi-tone blocks that repeat between these two editions:

| 1597 | The possibly 1611 edition |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The 1604 edition has similar pages that sport two-tone presentation:

But these books are not the same.

That 1604 edition… It’s curious that there are no blocks that are in the other two Siebmacher works that are also in the 1604 edition, yet all three books are clearly signed by him. And the majority of the block labels that show stitch counts for the repeat, or pattern height in units – they are curiously different between the 1604 and the others, too. But still, there evidence of style affinity across the works. Zeroing in on some specific pattern features:

A very familiar stag, that shows up on some of the earliest samplers, with descendants on American Colonial samplers, all the way up to pieces done in the 1800s.

| 1604 | 1597 |

|

|

Similar, yet not the same.

Here is a set that’s confounding. First the hippogriff and undine from 1604:

Compare the item above to these two designs – a winged triton and an undine, each from the 1597 work:

|

|

Lions rampant?

| 1604 | 1597 |

|

|

Even the geometrics are close but not duplicates

| 1604 | 1597 |

|

|

All this aside, even the seemingly close 1597 and possibly-1611 versions have significant differences between them, although they do have exact page duplicates between them. Not so with 1604 – it’s unique when closely compared to the other two, even though all three have the same author attribution, and very similar styles. This is VERY odd considering the vast amount of physical labor that had to go into producing these blocks.

So. What’s going on with the 1604 edition? Why is it so different from the other two? Has anyone read an academic work that examines this issue in more detail, or corroborates these findings with other editions that are not published on line?

So many patterns, so many questions, so little time to do in depth research.

HOLIDAY REPORT

Altogether a satisfying holiday season here at String Central.

We started off festivities last Friday, with a latke-fest.

We decorated the tree and deployed the M&M Man Army on Christmas Eve day, while the dinner was cooking:

There’s no such thing as too many ornaments in this house, but with so many on the tree, the special ones get overlooked. So they go on a small wrought-iron stand that sits on the coffee table:

Saturday brought Christmas Even dinner. The Resident Male outdid himself, with lobster bisque, pan-seared foie gras, a succulent and crispy-skinned roast goose with chestnut stuffing, ragout of wild mushrooms, and roasted golden beets. He even made an apple charlotte for dessert.

Sunday morning was rife with the traditional anticipation until everyone was awake:

Christmas day was another goose. (You can’t beat a two-goose holiday!) This time at the now-traditional gathering hosted by an old friend. It started as an “orphans’ holiday” in which those of us who had not gone to visit family for Christmas celebrated together. Over the years the gathering has become its own family, with themed dinners. This year’s was Swedish, with a warm and savory fruit soup to start, mushroom tarts, gravalax, the goose, three-meat stew, cream cake and many other goodies I’ve omitted mentioning. And a lot of good fun.

In terms of holiday present haul, I made out like a book bandit, courtesy of The Resident Male and Elder Daughter. Chief among my booty are these two volumes from the husband:

Needlework Through the Ages by Mary Symonds Antrobus and Louisa Preece is a huge tome published in 1928. It’s lavishly illustrated with photos (most black and white but a few in color). It’s a general survey course of embroidery starting at earliest known bits, through the end of the 1800s. A highly opinionated survey, I might add. Many of the photos are of items that are still in private collections, rarely included in other works. I will have much fun reading this, raising eyebrows at the authors’ various diatribes, and exploring the photos it contains.

My other gem is L’Histoire du Costume Femmes Francais 1037-1774 by Paul Louis de Giafferi – the first volume of a two-volume work issued around 1925. (The second volume spans the years from 1774 through 1870.) Each volume contains multiple albums of illustrations – stencil colored (as opposed to ink press printed) – with accompanying descriptions. Some of the plates from this first volume are available on line, and some are available in a 1981 paperback re-issue. But the original is magnificent. And inspirational! My French may be rusty, but reading is easier to speaking, so this is more than a “pretty pictures” book, for sure.

He also gave me a contemporary work, Viking Clothing by Thor Ewing. This looks to be an excellent reference for accurate re-creation of men’s and women’s dress of the period.

Elder Daughter also caught the historical spirit, but in a lighter mood. She gave me Kate Beaton’s book, Hark! A Vagrant. Highly funny. And Younger Daughter crafted paper sculptures. For me, a swan basket. For The Resident Male, a desk dragon:

Low key festivities continue, with the majority of us being all or mostly off from school and work. Hope your holiday is similarly pleasant, filled with family, friends, good food, and fun.

KNITS OF THE TIMES

Several small developments on this end. First, I’m up to the final corner on my gray/brown shawl. One more night’s knitting should put it to bed. Then it gets added to the ever growing to-be-blocked pile. Second, I’ve decided I should take personal steps to decrease the “overweight, middle-aged women who knit” demographic. Since I can’t do much about the passage of time nor do I have any intention of abandoning my hobbies, I have embarked on an exercise program. I won’t speak about it again until it produces some sort of result. Third, the bathroom renovation is now in its final step – painting. I’ve spackled, sanded, and washed down the walls. I’ve cut in the corners with primer, and am about to roll the walls and ceilings with that base coat. After that comes white ceiling paint, plus a white tinged with green for the upper parts of the walls above the railroad tile. Pix when I’m done.

For the meat of this entry, last week the New York Times announced that it was throwing part of its archive open for free access. People who have registered with the site (a painless, no cost, and non-spam-generating process) can view most articles prior to 1928 or so, plus a subset of articles after that point without paying. Needless to say, I took advantage of the opportunity to see what early knitting-related material might be there.

The New York Times was never noted for frivolity and never ran a crafts or continuing women’s interest column that published needlework interest items, therefore it’s not surprising that I found mostly business- and war-related knitting articles. I found quite a bit of interest to textile historians – accounts of mills opening, burning, and closing down (all very common); reports on inventors or new processes; documentation of poor working conditions and worker exploitation. I did find some fashion commentary for both home and personal wear; but more on war knitting, describing materials distribution, yarn and needle shortages, yarn rationing (and the resulting protests), and famous people knitting for the cause. Amid all of this were some scattered patterns and knitting trivia.

Here are some of the most notable. Remember though that these are all written in the vernacular of their times. Few are ready-to-knit in the modern sense, but experienced knitters with a bit of perseverance should be able to make sense of most of them – especially the how to knit socks for soldiers piece from 1914. All are in PDF – remember you need to sign up with the NYT website to view these:

A human interest piece from 1908– warning of the dangers of knitting on trains and buses. Amusingly enough, I’ve seen this very same story repeated as a gentle caution against knitting on planes. Perhaps this is the ur-source of an Urban Legend.

Patterns from 1883 – includes knit over gloves intended to be worn over kid leather gloves for extra warmth that uses #16 needles (in between a modern US #00-#000 or 1.75 and 1.5mm); a simple lacy shawl knit on #14 (modern US #0, metric 2mm); and baby booties (also on #16s); and a sock using fine wool that looks like it starts mid-pattern – this last one may in fact be directions only for the heel. I’d need to experiment to confirm.

Fancy ornamented knitting accessories are nothing new. Silver plated and brass straights with fancy charms or jeweled button ends were offered for sale in 1917.

For Civil War period re-enactors and historical needlework buffs – a pattern for Soldiers’ Mittens with a separate forefinger from 1861 (aka shooters’ mittens). From the number of stitches cast on I suspect these can be worked from sport weight yarn today.

Again everything old is new again – carpal tunnel syndrome as a result of writing, sewing and knitting –described in 1882.

How to Knit Socks for Soldiers, 1914. Mrs. De Lancey Nicoll presents comprehensive prose instructions on sock knitting in excellent detail because “The trouble with American Women is that so few of them how know to knit socks. Practically only the foreign-born women know how.” Surprising because today we think that everyone in the past knew these skills. Excellent beginners instruction in sock knitting (and in period terminology), these socks are standard 5-needle top-down socks with a drawstring toe, calf shaping, and a gusseted heel, worked on size #14 needles (US #0 or 2mm). They start at 80 stitches above the calf, but narrow down to 60 at the ankle, making them dead on for modern fingering weight yarn and a fit close to contemporary socks. Plan on at least 200g of sock yarn to make a pair of these. Probably a bit more.

War work, this time from 1917. The illustrious Mrs. Leeds offers up patterns for knitted sleeping socks (#12 needles, around modern #2 or 3mm, but the 84 stitches around make me want to work this pair on #000s or 1.5mm). Also two crocheted scarves – note that worsted is not a yarn weight descriptor for these, instead it specifies a twisted multi-plied long fiber staple yarn of high quality. I’d use a light fingering weight or 3-ply baby yarn. Directions also for an abdominal band, and two knitted helmets.

Official Red Cross patterns for war knitting, also from 1917. Again Mrs. Leeds – the knitting and crochet instructor for the Atlantic City Red Cross – is mentioned. This collection includes wristlets, a trench cap, knee caps, a sleeveless jacket (pullover vest); a helmet, muffler, and jacket. There’s also a bath mitt, eye bandage, and crocheted hospital stockings.

1917 war knitting again – a plea for knitting to comfort sailors. This includes cursory directions for sleeveless jackets (vests), wristlets and mufflers. These three garments were considered a set. The article points out that each battleship requires 500 sets of these garments and each submarine, 20. This article, also from 1917 also mentions the Navy sets, and offers Red Cross directions for an abdominal band.

From 1915, the most curious piece of war knitting I’ve ever seen. Invented by a French doctor, the “Multipurpose Garment” that appears to be a loosely knitted body-wide strip with a head hole. The idea is that it can be used or worn in several ways: flat as a comforter; or with the sides laced up in various manners, making the thing into the equivalent of a sleeveless vest, an upper body cropped sweater, or swathed around as an odd looking combo abdominal band/balaclava. This may be worth knitting up just to see what it looks like.

Embedded in this 1910 women’s column is a cursory description of a crocheted afghan – long strips of plain crochet, joined with openwork.

From 1911 – cursory directions for a striped knit afghan, in a women’s interest column that also warns about the dangers of diet pills.

And finally a cast-on hint from 1907 – use bigger needles when you cast-on.

I hope someone finds these bits entertaining and useful. If you attempt to knit from any of them, I’d love to hear about the result.

PRESENTS!

My self-awarded belated birthday present has arrived! I ordered three specialty books on lace knitting, only one of which is in English. They’re not out of print, but I don’t have a separate blog category for current works, so they’ve ended up under that classification:

My first present to me is The Knitted Lace Patterns of Christine Duchrow, Vol. III, edited by Jules and Kaethe Kliot. It’s 144 pages in German, with an English foreword and symbol glossary. The patterns are presented in the same graphed format as the Volume I book I am knitting from now. This collection is a bit larger, and is mostly home-decorative items (doilies, tablecloths, tea cloths, and a smattering of counterpanes), although a few caps, stoles, collars, jabots, and a blouse are presented, too. These 100+ patterns are also quite a bit more complex than the ones in Vol. I. I’m especially interested in the large oval shaped doilies, and in a a curious appendix of hand-drawn charts, in another somewhat related notation set, but unaccompanied by as-knit photos. Plus there’s one unusual geometric insertion strip (p 86) and a photo of a lace edging (p.2 but no graph or English pattern provided), both of which may end up on my current very geometric stole. I’m very pleased with this one. The hand-drawn appendix is an appreciated lagniappe, but it is haunting me. I’m too much of a Pandora not to want to discover how those charts knit up.

Old World Treasures is 35-page leaflet in English, presenting patterns entirely in prose notation in a relatively large 12-point font (fellow bifocal victims, take heed!). The 21 patterns mostly for small motifs knit in the round (in the 40-75 row range), useful for doilies, insertions, cap backs, and the like. Three of the patterns are much larger, with one going up to just over 200 rows, and another appearing to be composed of eight smaller doilies stitched onto a larger separately made complementary center. There are motifs with 4, 6, and 8 sided symmetry. Stitch counts at the end of significant rows are given, which is a help. I’m not a big fan of prose directions, so my first step in working from this book would be to graph up anything I knit from this leaflet. Still, I am sorely tempted to attempt a “flower garden” sampler throw based on the centers of the various motifs presented. To do that I’d select either the 6-side or 8-side symmetry patterns and work them all up to the same row, then stitch them together with some plain (or simple leaf-bearing) motifs to complement their mixed complexity. There’s ample food for thought here.

The last book is Knitted Lace (Kunst-Stricken), also edited by Jules and Kaethe Kliot – a 71-page collection of patterns by Marie Niedner. This is another collection of lacy knitting patterns of German origin, and using another early charting system unique to this particular original author. The designs presented are considerably less complex than the Duchrow ones, and includes a fair number of less-lacy textures. The charts are relatively small, and are not always near the text and illustrations they accompany. The collection includes edgings and insertions (many of which are closely related to patterns in the Walker treasuries), plus a strip sampler collection, several long-armed lace fingerless mittens, a couple of counterpanes, the expected flock of doilies and table spreads, plus bonnets, a couple of lace stoles and lace/beaded drawstring purses, and a couple of blouses/jackets – one of which may be intended for a baby or toddler. One quick idea gleaned from this book is an interesting way to finish out scallop shell motif counterpanes using half-motifs to eke out the left and right edges. While there are some interesting pieces here, this book is of as immediate inspiration as are the other two. Had I been able to browse the contents prior to purchase, I might have opted for the second Duchrow volume, or two more of the Penning-edited leaflets in its place. Still, I am not disappointed, and will be working something from this book. Someday.

On an entirely different front – I’ve mailed off my No Sheep Swap package. I included a ball of one of my favorite non-wool blends, a couple of beaded stitch markers of personal significance, and a vintage pattern magazine from my collection. I hope the package gets where it is going because my downstream swap partner never wrote back to confirm her address or preferences.

AMAZING ON-LINE REFERENCE LIBRARY

Out web-walking again, I’ve stumbled across a treasure trove of books on spinning, weaving, and other textile arts. It includes historical and recent works on lacemaking, embroidery, tatting, knitting, crochet and some other less practiced crafts, as well as ethnographic material, periodicals, and academic papers. I’m sure I’m the last to find out about it, but I share the reference all the same.

This textile-related archive is maintained by the University of Arizona. Its collections are available on-line, with the individual works so distributed either aged out of copyright, or presented with the authors’ permission. There are thousands of items – mostly geared to industry and manufacture, but with a healthy smattering of works detailing hand production. Scans are available as PDFs, with the larger books broken out into smaller segments of under 15MB. Not all are in English.

Among the works I found that are of greatest interest to me in specific are:

Whiting, Olive. Khaki Knitting Book, Allies Special Aid, 1917, 58 pages. PDF

This compendium of knitting patterns presents sweaters, wristlets, socks, scarves, mittens, hats, caps, and baby clothes intended in part for troops overseas during WWI, and for the comfort of refugee families displaced by the war. Patterns for knitting and crochet are both included. The socks shown mostly knit top-down, some have a gradually decreased instead of grafted toe. Some of the socks are worked on two needles and seamed. One pair in particular (marked as a pattern from the American Red Cross, p. 13) seems to include a written description of a grafted toe, but it does not name the technique. Directions are a bit more detailed than is usual for pre 1940 knitting booklets. Fewer than a quarter of the patterns are illustrated with finished item photos. Aside from a list of abbreviations in the front, there are no how-to or technique illustrations.

Nicoll, Maud Churchill. Knitting and Sewing. How to Make Seventy Useful Articles for Men in the Army and Navy, George H. Doran Company, New York, 1918, 209 pages. PDF

This book is a bit more detailed than the previous one. It also contains a rundown of standard troop knitting patterns – hats, mufflers, balaclavas (called helmets), mittens, socks and the like. Every project is illustrated either with a photo or a line drawing of the finished product. Instructions are written out in a fuller format than in the Khaki Knitting Book. It also has some valuable bits of instruction including a list of yarn substitutions, plus two full size color plates showing the wools used, identified by name; a small stitch dictionary section,

Of special note are some unusual mittens (including a mitten with truncated thumbs and index fingers – p.68), half-mittens – p. 77, “doddies” or mittens with an open thumb, p. 80, and double heavy mittens intended for seamen or mine sweepers hauling cables – p. 94). The grafting method of closing up sock toes is clearly described AND illustrated, but it is called “Swiss darning” (p.131). I’ve heard that term used for duplicate stitch embroidery on knitting, especially when the decorative stitches are sewn in rows mimicking actual knitting, rather than being stitched vertically, but I have never before seen it applied to actual grafting. The entire section on socks and stockings is particularly clear and useful. There are even a couple of crocheted and knit mens’ ties in the sewing section.

Finally, the sewing section (about a quarter of the book) might be useful to people doing historical costuming or regimental re-creators who are looking to augment their kit. The one drawback is that most of the sewing patterns are predicated on Butterick printed patterns, and the schematics are not provided in the book. Among the offerings are money belts, a chamois leather body protector and waistcoat, various types of shirts and undergarments, pajamas made from heavy blanket fabric, and a book bag (like a messenger’s bag).

Egenolf, Christian. Modelbuch aller art Nehewercks un Strickens, George Gilbers, 1880, 75 pages. Note: Reprint of 1527 book. PDF

Ostaus, Giovanni. La Vera Perfezione del Disegno [True Perfection in Design], 1561, 92 pages. Note: 1909 facsimile. PDF

These are two modelbooks of the 1500s. There are several others in the collection, but they are mostly books of needle lace designs. Ostaus also offers up mostly patterns for the various forms of needle lace, plus some patterns that can be adapted to free-hand (as opposed to counted) embroidery, plus a large section of allegorical plates to inspire stitched medallions, slips, and cabinets. One thing I’ve always liked are some of his negative/positive patterns. These are designs that if laid out on a strip of thin leather or paper and cut can be separated longitudinally into two identical pieces. There are several of these scattered around the middle of the book.

Starting around page 73 or so there is a section of graphed patterns, a number of which landed in my New Carolingian Modelbook collection.

The Egenolf book also is mostly line drawing suitable for freehand embroidery. Some are pretty cluttered, but some are very graceful. The oak border on p. 32 has always been one of my favorites. There’s one plate with a counted pattern, on p. 72.

—. Priscilla Cotton Knitting Book, Priscilla Publishing Co., 51 pages. PDF1, PDF2, PDF3, PDF4, PDF5, PDF6.

This books is obviously a seminal source behind many of today’s reference books on knitting technique and patterns. Notation is sparse and “antique” with n (narrow) being used for k2tog, and o for yarn over, and other oddities. There’s a fair bit of circular doily knitting, but it is of the knit radially and seamed variety seen also in Abbey’s Knitting Lace. In fact many of the doilies appearing in Abbey appear to have been adapted directly from this work. You’ll also recognize many Walker treasury edging patterns in these pages.

In addition to the stitch texture and lacy knitting sections, there’s a bit on “cameo knitting” which appears to be another name for stranding (in PDF2). The section on filet knitting (in PDF3) is relatively extensive, and clearly shows both the strengths and weaknesses of this rarely described style.

—. Priscilla Irish Crochet Book No. 2, Priscilla Publishing Co., 52 pages. PDF1, PDF2, PDF3, PDF4, PDF5, PDF6, PDF7, PDF8.

This has got to be the single most complete and eye-popping source I’ve ever seen on Irish crochet. Not only does this contain an amazing amount of eye candy, it also gives directions on how to create it, offering up pattern descriptions for the individual motifs, the joining brides and grounds, and the working method of fastening the motifs to a temporary backing while the grounds are being worked.

—. Egyptisch Vlechtwerk [Sprang], Holkema & Warendorf, 36 pages.PDF1, PDF2

As an example of the depth of the collection, here’s a work on Sprang, one of the lesser known fiber manipulation crafts sometimes mistaken for early knitting. It is in Dutch and appears to be from before WWI, but it is illustrated with photos of finished pieces and works in progress.

These are just a small sample of the hundreds of works available at the University’s website. Again, most are on the industrial aspects of the textile arts, from fiber acquisition (including sericulture and sheep raising) through spinning, and weaving, but a goodly number are of direct interest to hand-crafters. Topic lists exist for knitting, crochet, embroidery, cross stitch, lace, tatting, and a multitude of other subjects. Support this valuable resource by visiting and using it. I know I’ll be combing through here for years…

ANCIENT KNITTING BOOKS ON THE WEB

Back to a series started long ago, I present more summaries of out of print knitting-related books. But instead of exhuming these from my local library system, I found the full text of these works on-line via a Google Book Search.

Directions for Knitting Socks and Stockings. Revised, Enlarged and Specially Adapted for use in Elementary Schools, by Mrs. Lewis, printed in London in 1883 is a pamphlet written in response to a bit of British educational legislation, mandating that all girls be required to learn to knit. Aside from pedagogical pedantry in service of this goal, it does provide some interesting bits, although there are no illustrations. Pages 12-14 contain a comprehensive “sock recipe” chart, listing numerical sizes and the numbers of stitches to be cast on, and the number of rows or stitches that compose other sock and stocking features (rib depth, length to heel, heel stitches, length of foot, etc.). This chart however does not present gauge or finished measurements. From the measurements however, it’s pretty clear that gauge is quite small by modern standards, with the smallest boy’s sock size starting off on a 49 stitch circumference, and the largest man’s sock size starting off with a 121 stitch cuff.

Prose directions to accompany the charts begin on page 15. They describe socks with Dutch style heels. I would not recommend this booklet for a modern knitter starting off on his or her first pair of socks because the description style used in the directions is obtuse by today’s standards, although for the time – the instructions are pretty clear. But if you have done a Dutch heel before and are familiar with it’s components and features, you will be able to follow along.

The leaflet goes on to present directions for Muffatees with Thumbs (page 24) – fingerless mittens, but knit flat rather than in the round, and are worked sideways rather than parallel to the bottom edge of the cuff and seamed up the center of the palm. Wrist ribbing is constructed from knit/purl welting. This pattern is a little bit more accessible, although the description of picking up and knitting the thumb is a bit of a stretch. (I’m thinking of quickly trying this pattern out and posting the redaction here if anyone is interested). There’s also a beginner’s scarf knit in the flat, featuring a simple fagoting detail running its length. The booklet finishes with a description of various historical yarns. Names and in-skein weights are given, but aside from an estimate that a certain weight should be ample to produce a pair of socks – no yardage is described.

The Lady’s Assistant for Executing Useful and Fancy Designs in Knitting, Netting and Crochet Work, by Mrs. Gaugain, London, 1847 is one of those Ur books that informed later generations of stitch pattern reference works. I’ve seen it mentioned in bibliographies, and was excited to find it on Google. Sadly, I was very disappointed. Although it is listed as containing over 220 pages, the scan cuts off around page 70 or so, and of the initial 70, quite a few are skewed, truncated, or flat out missing. None of the netting or crochet sections are included in the on-line version. Given the difficult notation and lack of illustrations, I’d need more patience and perseverance than I have to spare tonight to make much headway with the contents.

The Young Ladies’ Journal Complete Guide to the Work-Table: Containing Instruction for Berlin Work, Crochet, Drawn-Thread Work, Embroidery, Knitting, Knotting or Macrame, Lace, Netting, Poonah Painting and Tatting, London 1885. This one is a bit more promising, more along the lines of Weldons Encyclopedia volumes or the illustrated needlework sections of Godey’s Ladies’ Book. The crochet section includes some nicely done illustrations of basic techniques, including a basket pattern I’ve not seen before (p. 12); and excellent illustrated beginners’ guides to Guipre style darned netting. The knitting section is relatively advanced, with descriptions of gauge and its importance. There are a few texture patterns shown – nothing that hasn’t made its way to modern sources; plus counterpane edgings and motifs, stockings, knee-caps, baby shirts and other items. On page 52 theres an interesting shawl, knit using two weights of yarn to produce a honeycomb line effect with lacy infilling. There’s also an unusual welted insertion pattern similar to the pattern shown on the cover of Lewis Knitting Counterpanes, except that in this case there’s no bundling of stitches using wraps ( p. 61).

I also liked the point lace (needle lace) section. The first style shown would be familiar to most people today through the Battenberg lace style, it is rarely illustrated in contemporary works on stitching and needle lace. This book shows various infilling needle lace patterns for use inside of the outlines formed by the loops of purchased woven tape. Other forms of point lace are also shown,

Poonah painting apears to be some sort of stencil work done with enamels and varnishes, applied to both hard surfaces and textiles. I have to admit I wasn’t that interested. More interesting was the macrame and tatting section. This is macrame as in fancy finework fringes – not heavy cording tied into owls or plant hangers. I have used some of the simpler style fringe tying patterns on scarves and knit blankets. They add another layer of complexity to the designs, and look much more finished than do fringes attached and left otherwise untied.

The book finishes up with brief sections on drawn and withdrawn thread embroidery styles and on some of the fancier forms of knotted netting.

BACK FROM THE DEAD & ODHAM’S ENCYCLOPAEDIA

From the "This too shall pass" department, I announce the end of the work project that ate my life. The final submission was yesterday. I am now left with a horrific clutter in my office, several thousand megs of files that need to be classified and archived, and the need to make up for eight weeks of sleep deficit. But all that aside, I also can now get back to String and wiseNeedle.

I’ve processed in the backlog of posted yarn reviews on wiseNeedle, and am about to start tackling the questions inbox. Since so many questions are duplicates of ones already answered at the site, there will be lots of "Did you look here?" notes. If you’ve posted a question since around mid-January and you haven’t heard from me, apologies. I am whittling away at the stack…

In the mean time, courtesy of my long-time stitch pal Kathryn, I can post another review of an out of print Knitting Book that Time ForgotTM.

ODHAM’S ENCYCLOPAEDIA OF KNITTING

We’ve all heard of James Norbury from his other knitting books. The most notable one is his Traditional Knitting Pattens from Scandinavia, the British Isles, France, Italy, and other European Countries. That’s the one that’s been widely reprinted by Dover Books. I mentioned it in another round-up of older knitting books two years ago. In January Kathryn sent me a copy of another of his products – Odham’s Encyclopaedia of Knitting, written in concert with Margaret Agutter. My copy is missing its title page, but searches in used book store inventories turn up 1955 to 1959 as the probable date of publication for my edition. Oldham’s is copiously illustrated with line drawings, sketches and a few black and white photos of finished garments. Based on the style of of the little thumbnail cartoons and some of the on-the-needle drawings of knitting in progress, I suspect that one of the many illustrators on this project also worked on the Mary Thomas books.

The book starts with a section on knitting history – nicely done and less folkloric than most contemporary works, although not entirely without hyperbole. 19th and early 20th century knitting is outlined, with references to many works the authors considered seminal in developing modern knitting technique – books and pamphlets I am now hungry to read. The meat of the book is somewhat choppily arranged. The first 70 some odd pages covers basic techniques, and is arranged alphabetically under broad subject areas. The instructive tone is very British-centric. For example, Continental style is mentioned as an aberant variation of "normal knitting," with the caution that it is inferior for maintaining even gauge. Grafting is described both for stockinette and K1, P1 ribbing (done in two passes on each side of the work rather than as a linear row). You have to look hard for it though, as the heading that starts the grafting section seems to be missing. As in all non-North American publications of its time, the name "Kitchener" is not associated with that technique. Crochet stitches are shown in this section, too.

The next section deals with fabrics and patterns, and covers some of knitting’s basic styles. It commingles them with texture pattern family descriptions (including directions for some of them), offered up as separate mini-articles. Therefore you’ll find small bits on Aran (it’s resemblance to Austrian knitting is noted); Argyle; bead knitting; Bohus; Faroe; Florentine/Jacquard (we’d call it Intarsia); Scandinavian styles; Shetland; and Tyrolean knitting all mixed together with general descriptions of the families of cable stitches, feather and fan stitches, leaf stitches, bobbles, etc. Instructions for samples of the various stitch families are presented mostly in prose, although graphs are used to show colorwork and motif placement.

Lace knitting is next. While the section does go into several styles, it looks almost like it was written by committee. There are at least four different illustration styles used, some being so representational as to be almost useless to the knitter. Most lace directions are given in prose, with a limited number at the end of the chapter being done in charts with symbols unique to this book. It’s difficult to tell from the bulk of the patterns exactly what they will look like, but the majority are covered in much better clarity in recently published lace books. The exception is the group of "Viennese Lace" texture patterns. Eventually I’ll explore these further.

Norbury/Agutter go on to describe the design of classic knitted garment shapes. There are sections on Cardigans and jerseys Yarns employed range from three-ply to DK, and sizes/styles are 1950s tight. While sizes are small, there’s a fair amount on darts and tailored shaping here that might be of use to people trying to do retro design today. Of more immediate use are sections on gloves, socks, berets and tams, and baby clothes. Directions for a single basic garment are given in prose.

The final part of the book is a compendium of garment patterns, again all in prose and to 50’s size and fit. Patterns are provided for the items shown in the black and white photos. Gauges are small by modern standards, with most items knit from fingering weight. But there are several cardigans and pullovers in DK weight, plus a couple in doubled DK weight (3.5spi, the equivalent of what one would expect from a modern bulky weight yarn.)

Like many of these older knitting compendiums, there’s a strong ideological bent , a smattering of fashionable garments to keep one interested , and enough detail to pass itself off as a general purpose handbook. But books like this weren’t aimed at people with absolutely no knitting experience. The level of detail they provide is insufficient for a beginners’ guide. Rather they were shelf references. Places an intermediate knitter could go to broaden a skill set, or brush up on a forgotten technique. Finishing for example is given very short shrift. Blocking is explained, but how one goes about accomplishing the "sew up" command at the end of each pattern is never quite elucidated.

Are modern books better? Yes and no. Some are, both as shelf references and as beginners’ guides. Some are shorthand cribs on just a few basic concepts, quick to master and trendy enough to look dated after only a year or two. Others do contain a fair bit of info, but like this particular book, aren’t organized in a way that works as a reference or as a skills guide.

Would I recommend buying this book used? While it’s certainly worth the time to look through on library loan, unless you’re a needlework history book buff (like me), I’d give it a pass. For me though it is valuable, partly for its interesting history of (mostly British) knitting before WWII, and for its mystery lace chapter. So thank you Kathryn! Although you were right that this book isn’t for everyone, it is a worthy and appreciated addition to my library.

NOT SO OOP BOOK REVIEW – FOR THE LOVE OF KNITTING

Thank you for all the get-well wishes. I’m still flu-laden, and now joined with two sick kiddies at home, I am at least clear headed enough to sit vertical, type and knit. I don’t know where this particular bug came from, but it appears to take 10 days to run its course. An eternity of delight…

For the Love of Knitting

Despite some huge budget problems, my local library is still getting a trickle of new books. Patrolling the new book shelves, I found For the Love of Knitting: A celebration of the Knitter’s Art, edited by Kari Cornell (Stillwater,Minnesota: Voyageur Press, 2004).

This one is a knitting coffee table book. Big format, copious, colorful illustrations, lots of "name appeal," but little content. It’s a collection of essays by the likes of Zimmerman, , Falick, Swansen, Klass, and other knitting writers. About a third (including the Zimmerman, and Klass pieces) have appeared before in magazines, newspapers, and even in other knitting inspiration books like Knitting Lessons, Knitting Sutra, and KnitLit. I was surprised to see so much material mined from recent sources and reprinted in a book of this type.

While this book is certainly pretty, and the essays are interesting, no one is going to learn anything new from this book. There are no projects. There are no descriptions of techniques. The majority of the pictures are of knitting booklets from before 1960, shots of yarn baskets, archive photos of knitting and knitters, and pictures of knitting in art. Only a couple of the essays have pictures of immediate relevance in them. In terms of garment inspiration, there are a couple of close-ups of some of Solveig Hisdal’s stranded work (taken out of context because the whole garment isn’t shown); plus several shots of "art knitting" – a couple of wearables, plus various soft and hard installations incorporating knitted fabrics. Very little for a book so large and so copiously illustrated.

I also found the editorial tone of the thing got increasingly irritating. An example the caption on a Russian postcard, found on page 50. "Knitting Companion: In this quaint Russian postcard, a young woman keeps one eye on her knitting and another on her cat, who looks about ready to pounce on the next free stand of yarn." I can see the picture. there’s no reason to describe it in the caption. I want to know more about the postcard. Were such things common? When was it made? The style in the picture makes me think it might be from the 1920s. A Russian postcard from the 1920s? There has to be a story there, but there is no further attribution or sourcing for the postcard. Nothing whatsoever beyond showing the picture and then describing it overly cutely.

So if a sample course of essays describing knitting (as opposed to knitting technique), illustrated with patronizingly described eye candy appeals to you, you’ll probably enjoy this rather formulaic book. If nothing else, you may find a first taste of someone’s writing here that would lead you on to her or his other works.

Final verdict: Save yourself the $30.00 cover price. Borrow this one from the library.

00P BOOK REVIEW – KNITTING STITCHES AND PATTERNS

A minor setback on the Rogue today. The needle got pulled out of the pocket stitches, probably during an energetic pillow fight last night. No great harm done and I can’t apportion blame as I was a participant, but it was more than judicious picking up with a crochet hook could fix. I ended up raveling back a couple of inches to even everything out. I’m now at exactly the same place I was the day before yesterday. So apologies if you came looking for progress. There ain’t none.

Instead I offer up yet another book review of an older off-the-library-shelf book.

Knitting Stitches and Patterns

This book was written by Diana Biggs, copyright 1972, and published by Octopus in London. Biggs presents a basic knitting course, couched entirely in garment patterns. Her directions are clear and well written, and the book has lots of color photographs. After a knitting skill overview section, she shows the obligatory beginners scarf and other intro patterns, but quickly plunges into shaped garments, starting with a sleeveless vest. Fit is tight by today’s standards, and armholes are cut high, but they are shaped armholes for the most part, not dropped shoulder pieces.

If you want to know what people were REALLY wearing circa 1968-1972, this is a pretty good source. It’s not the most fashion forward representative of its era, but the designs are the sort of thing I remember both my mother knitting, and everybody wearing.

The later chapters include more detailed exploration of traditional styles, with simple Arans, yoke-style Fair Isles, and ganseys. There are also lots of relatively plain but well executed raglans, vee-neck striped pullovers, and short sleeved lacy tops. There are a few very classic looking mens sweaters in the mix.

The accessories and kids garments hold up even better than the mens pieces (mostly because the fit of the adult sleeves is too high). All of the kids garments could be knit and worn today. There are a couple of quite charming kid-size ganseys, plus jumper/pinafore style sleeveless dresses, meant to be worn over a blouse, or in a summer cotton – alone (jumpers if you are in the US, pinafores if you are in the UK). There’s even a side trip into knitting with beads; and a side trip into lace knitting, with patterns for a square and a round lace doily. Other features include some socks, home decor items, and some toys including a knit Gollywog doll that may or may not straddle the cultural line between "quaint" and "in questionable taste," depending on your own background.

One final useful feature – in the back of the book is a chart offering up yarn substitution suggestions for knitters in the UK, the US, Canada, Australia, and South Africa. While? not all the yarns in the book are included, and most of the substitutes that are mentioned are long gone, having a big range of suitable yarns makes finding modern subs easier.

This two page spread is of an elongated stitch triangular shawl, done in a glittery yarn (Goldfingering, the glittery yarn used is still widely available) and a silky finish yarn; plus a zip-front tunic top or dress, done in a textured two-tone yarn. Please excuse the poor picture quality. I believe this book was originally a soft-cover. The copy I borrowed from my library has been re-bound with one of those heavy and anonymous green cloth library bindings. It’s very tight and I had a lot of trouble trying to get it to lay flat enough to photograph, even with a book weight.

On the whole, if you run across this in a library, take a peek. If you find it in a second hand shop and are partial to pattern books and are in the market for something to help plan a first or second project, it’s well worth the used book price. I see dozens of copies on line for under $5.00 US – some lower than the price of a single sheet pattern. While even for its time it wasn’t as trendy as the various urban knitter/hip knitter beginners pattern collections today, it does offer a set of useful basic patterns, plus more technical meat than any of them.

And I do note that styles ARE cycling back to fitted armholes and away from drop shoulder boxy things…

The brown ink on the G near the talon matches the color of the hand-drawn designs at the back of the book – post-publication additions.

The brown ink on the G near the talon matches the color of the hand-drawn designs at the back of the book – post-publication additions.