WEB WALKING THROUGH RUSSIAN KNITTING AND CROCHET

UPDATE: It’s January 2022 now, and I note that this old post from 2006 is getting a lot of attention. Please be warned that the Internet landscape has changed in the years since I wrote this. Many Russian sites are rife with malware. Some has been introduced via on-site ads that autoplay, some has been planted by hackers, so even innocent informational/hobbyist sites can be compromised without the viewer’s knowledge. If you do go wandering through Russian hobby sites, please be sure you have robust, up-to-date virus protection, and avoid downloading material of any type.

——- Original post below —–

I am having a fascinating time this weekend noodling out Russian language pages on knitting and crochet, and trying to translate some terms. I started doing this because I had (dimly) remembered some Russian language stitch dictionary pages that offered up a slightly different collection of texture patterns from those that commonly seen in English language books. I remembered some that employed ornamental floats, so I wanted to find them again. Now bear in mind, I don’t speak or read a word of that language. My assumptions here are going to range from reasonable to laughable. But I’m having fun none the less.

I started my search with the one English character transliteration of a Russian word that I did know from prior searches. I have no idea how the original is pronounced, but in what looks to be a one for one letter swap, Latin alphabet for Cyrillic, uzor (plural uzori) appears to mean stitch or pattern.

I used that term to do a Google image search. When I found an image that was interesting, I clicked through to the parent page and followed some of the in-page links there. Along the way I kept a notepad file open, gluing in copied terms in both the original Russian, and the Latinized spellings frequently used in Web page URLs.

Here are some of them, along with my wild-ass guesses on what they might mean.

– uzori or uzory – patterns (possibly also stitch designs)

– stitches

– knitting, probably also crochet work

– Crochet

– socks

– hats or caps

– table linens, including doilies and runners, but also napkins and cloths

– chart or diagram

– motifs?

Along the way, I found a couple of interesting patterns. Here’s one for a lace doily. Its pattern page presents some useful visuals, including starting a doily center using the crocheted circle method, blocking hints, and (of course) the chart for the piece itself.

Now I had a second problem. I can knit from a chart in any language, provided I have the symbol key. What do the chart symbols mean? It’s hard to cut and paste the chart terms into on line Russian-English dictionaries (this was the best one for my purposes) because for the most part, the terms are there as images, not text. Sadly though Russian knitting symbol interpretation seems to be just as jumbled as Western charting, with different sources using either different symbols to mean the same thing, or using the same symbols but employing them differently. Looking over the lace chart for the doily above, I suspect that straight vertical lines are knits, the little arrows facing left are knit through the back of the loop (ktbl). U must be a YO (perhaps U with the 2 in it is a double yarn over), and downward facing Vs are decreases (numbers in the arms of the V indicate the number of stitches to be decreased). Obviously lots of experimentation is in order here to confirm (or disprove) these guesses.

Although I was hunting for knitting, most of what I found were charts for crochet. The crochet notation looks a bit more standard. Some of it seems to be similar to the notation found in Japanese crochet patterns. For the most part they look to be easily interpreted even if one doesn’t read Russian. Here are a few of the ones I liked best.

- A crocheted spiral doily

- An interesting crocheted stole or table runner

- A stole featuring a very mesh-like crocheted structure (click on the link to get the charts)

- A cushion pattern that could be adapted into a very nice lace scarf

- Yet another doily, this one that makes subtle use of some pineapple style features, but does so without being “yet another piece of pineapple crochet”

- Another small round piece. I like the contrast between the densely worked areas and the open net-line areas.

- A spectacular collection of small round, square, and other shape motifs. (I am not quite sure how Russian copyright law works but be aware that other pages on this site offer what look to be scans of full books)

And finally I found Russian language stitch patterns that do look like they exhibit some kind of wrapping.

- This one looks like the wrapping happens on the diagonal Perhaps this was done by reaching down a row or two and picking up a long loop, then knitting them off together with the current stitch.

- Photographed sideways, this one has a combo of horizontal wraps that gather the stitches enough to make a smocked effect.

- And this one clearly has stitches picked up several rows below. The chart is a bit confusing because it appears to be written for the flat, showing alternating rows of knitting and purling to produce the reverse stockinette texture. Most charts I’ve seen stick to “as seen from the front side” logic.

But I never found the dimly remembered patterns that set me off on this quest in the first place.

INTERESTING 18TH CENTURY CAP – ORNAMENTAL WRAPPING

A person posting on one of the historical knitting lists asked a question yesterday about this 18th century Spanish knitted cap. I’ve poked around the Victoria and Albert Museum’s on line photo collection, but I hadn’t taken the time to zoom in and look closely at this particular item.

At first glance the cap appears to be covered with knit-purl texture patterning, but if you zoom in (and especially if you have the ability to get an even closer look at the image) you’ll see that the texture isn’t formed by knits and purls. Instead, the design is made up of some sort of stranding that floats over a stockinette background. The question was about how this might have been done. Unfortunately, we can’t see the back of the work. So I got to thinking…

The most obvious way would be for someone to work up a plain stockinette cap, then hand-stitch the floats over counted stitches, to produce a diapered or pattern darned effect. This would certainly work, but lacks elegance. If I were making a hat like this, I’d much rather do the decoration at the same time as the base knitting, rather than going back later.

This leaves two methods – some sort of in-row wrapping, or slipping stitches with the yarn in front of the work.

Let’s look at slipping first. If you knit a row, then holding yarn in front, slip several stitches, and then resume knitting, you make a fabric that has a base row of normal height, then a distended area where stitches were slipped. If you continue to do this on subsequent rows without rows of intervening plain knit, you pull those stretched stitches up even further, creating a vertical column with a grossly distorted base structure. It doesn’t look like the knitter of this cap made the floats by slipping with yarn in front because if you zoom in and examine the long vertical bars of the ornamentation, a float seems to happens on every row, and there is no evidence of vertical distortion.

This leaves the wrap method. Wrapping stitches for ornamental effect isn’t widely practiced any more although it still survives almost as a curiosity in some cotton knitting. You can see an example of wrapped stitches in the cover pattern on the Lewis Knitting Counterpanes book published by Taunton Press. In this case the wrapping is pulled very tightly to magnify the gathered effect of the pattern. The wraps are peeking out beneath the bellies of the scallops:

I’ve also seen texture designs in European pattern collections that use wrapped stitches. There are a couple of the tight-wraps-as-gathers type at the end of Omas Strickgeheimnisse, a German-language knitting texture pattern dictionary. I thought there was at least one in the Bauerliches Stricken series (another 3-volume German stitch dictionary), but thumbing through, I can’t find it now. Some of the on-line Russian language stitch collections also show wrapped stitches I found these by searching for which may mean pattern or stitch in Russian. It also seems to transliterate to the letters “uzori or uzor” in Western alphabets, which are also good starting points for searches. (No I don’t speak or read Russian, I’ve stumbled across this bit of trivia while web-walking.) I don’t have time this morning to fish up the citations for these dimly remembered Russian texture patterns. I’ll have to leave that for tomorrow.

However, none of the contemporary sources for these wrapped stitches employ them in the way I envision that the Red Cap Knitter did.

I don’t think it would be difficult to do this, just a bit fiddly. I like fiddly. Remember that this is a thought experiment. I haven’t tried the method out yet. Perhaps over the weekend I’ll have time to do so. Here goes.

Let’s say you want to lay a ladder across four stitches. You knit the four as usual. Then you take your yarn and move it to the back of the work. You transfer four stitches from your right hand needle back to the left hand needle, then you move the yarn strand to the front of the work, laying it in the “ditch” between the first stitch to be wrapped and the ones that came before it. Then you slip those four stitches back to the right hand needle. You draw the yarn strand across the front of the work over the four, then return it to the back. You have now “lassoed” your four stitches. Give the thing a slight tug to maintain tension, and knit the next stitch as usual.

Now all you need is a suitable graph, and you’re set. (Credit: This particular graph has been researched by SCA pal Carol.)

MORE LACE LOOMING IN MY FUTURE?

Small progress on several fronts. First, I’ve finished the knitting on my red doily. I have done the ceremonial breaking off of the yarn, and am up to the grafting part. I will begin that tonight, possibly even documenting it with photos, if I can find a willing volunteer photographer in the house. I will also try to get to the blocking of both doilies this weekend, although pre-holiday preparations and work may intrude.

On the website front, our resident technical wizard is fine-tuning some aspects of the site and boldly slaying bugs. Comments should now be working properly. I have put some pointers on the old String site’s most popular pages, redirecting folk over here, so with luck some of the people who link to those pages will notice and make corrections before those pages go dead. I’ve also started to answer the backlog of questions on the advice board, add more of this season’s yarns to the database, and to learn Wiki syntax. I’m plotting out the KnitWiki structure right now, diagramming hierarchies and interrelationships on paper. Suggestions for areas not to miss, or for how content would be most usefully organized are most welcome.

In addition to all this stuff going on (plus heavy deadline pressure at work) I still haven’t worked the lace bug out of my system. I’m not quite sure what will be next up. I’ve got a ball of lace-weight linen in a natural ecru. It’s two-ply construction, with a small bit of thick/thin and linen slubbing going on. I got it at the one Maryland Sheep & Wool festival that I went to, circa 1996. For solid sections, it looks best on 1.75 or 2mm needles, so I suspect for a bit lighter, lacier look I’ll move up a size or two. Not quite sure of my yardage, but whatever it is, that’s all there is. I’m thinking of messing around and making something up, combining lacy stitches from Hither and Yon (two of my favorite sources), adding an edging, and ending up with something wearable. Perhaps a medium-sized rectangular or square scarf, able to be worn as a dress accessory (there’s not enough there for a huge shawl). One minor complication that should work itself out – I have misplaced my copy of Heirloom Knitting. I used it last when I was selecting the edging for the second red doily. The one I used came from its pages.

Or I might do Eunny Jang’s Print o’ the Wave Stole. She’s already worked out a simple layout using a traditional Shetland pattern and companion edging. The Print o’ the Wave design itself is visually complex, but very easy to work, with a logical 12-row repeat. Eunny has also done an excellent tutorial on lace shawl construction. The series goes on from the one on shawl construction (links are on the right hand side of her page) and includes a highly useful round-up of lace-knitting cast on techniques.

HALLOWEEN APPROACHES

Quick aside: I don’t know about you, but a small window onto a whole new universe of costume options just opened up for me and mine today. Too funny!

INSPIRATION FROM ANOTHER TIME

[Repost of material originally appearing on 25 August 2006]

Like socks? Ever hear of the socks shown at the Great Exhibition of 1851? No? You’re in luck. The Victoria and Albert Museum never forgets. Their collections are now searchable on-line. A bit of poking around brings up this set of images, socks from that very exhibition, when all things Scots and the latest advances in machine knitting were the rage.

Now don’t poo-poo machine knitting. Sock machines of that time required quite a bit of hand manipulation. How about these socks – stockinette, with some openwork, finished off with hand embroidery, from the early 1840s?

Socks too mundane? Contemplate Sara Ann Cunliffe’s exquisite cotton lace baby gown, knit sometime in the late 1800s.

White cotton lace knitting too late for you? How about a brilliant 17th century silk and silver brocade jacket, with a thumbnail opinion that it was probably knit on needles and not a frame. What do you think. Cut and steeked? I think so. Even at 17 stitches per inch, I’d love to make one…

Looking for wool? How about an early 1800s baby ensemble that looks like it inspired Debbie Bliss.

There’s 19th century bead knitting, too. And (amazing to me) 18th century beaded knitting! Not to mention hand-knitted lace doilies from the Azores (1875-1900); 16th century liturgical gloves, a Shetland shawl to die for (19th century), and lots of other stuff from every era since knitting impinged on Western consciousness.

Of course, if you prefer stitching over knitting, especially Blackwork or monochrome embroidery, there’s some well-known examples of that there, too. Also samplers showing motifs straight from early modelbooks. Even an Egyptian piece from the 14th-16th century I’ve never seen before. I’m in heaven.

DIGRESSION – BLACKWORK EMBROIDERY

[Repost of material originally appearing 10 August 2006]

My old friend Marian pointed me at a fascinating Web-based resource. The Web Gallery of Art. It’s an on-line (sort of) searchable collection of art images from pre-1800. I’m in the middle of thumbing my way through Renaissance-era portraiture, in part to plain old enjoy it, but also with an eye to the embroidery used on clothing.

Now the few folk who visit here may know that in addition to knitting, I’m a sucker for embroidery. Especially counted embroidery from before 1600. My favorite family of styles is often lumped under the term “blackwork,” and had a popularity run spanning about 100 years or so, until it morphed into other things and/or fell out of fashion for upper-class clothing, sometime between 1600 and 1630. It did however live on through its descendants (most familiarly some of the bandwork common on early samplers) and peasant embroideries of several regions Through these descendants some of blackwork’s substyles have enjoyed little renaissances in the centuries since.

So. What is blackwork?

Not to be facetious, it’s monochrome embroidery worked in black thread on white ground. Most but not all of the time. Non-black or multiple colors were occasionally used. Most people think of it as counted work – embroidery that uses the threads of the ground fabric as a foundation “graph”.. Again, most but not all of the time. Some sub styles are clearly worked on the count. Others may have been, and still others are clearly freehand drawn. Some people are under the impression that there are clearly defined national or regional substyles, with English work being distinct from say German or Italian. Again, that’s partly but not entirely true. If you’re unfamiliar with the basics, The Skinner Sisters website has an excellent survey of Blackwork styles available on line.

Here’s one of the most famous examples of band style blackwork, worked on the count. It’s seen on the sleeves of Jane Seymour, as painted by Holbein in 1536 (you can click on the images in the linked pages to display them in greater detail). Very linear, clearly done both two-sided and on the count in a stitch that today goes by several names – Holbein Stitch, Spanish Stitch, Double Running Stitch. Harder to see (peeking out just above the gold and red units at the edge of the bodice – is a tiny line of blackwork on Catherine of Aragon, painted circa 1525-7 by Lucas Horenbout. Catherine is often said to have introduced the fashion for blackwork to the English court.

Here are heavier outlines, but still very geometric, suggesting a counted ground to me: Pierfrancesco di Jacopo’s Portrait of a Lady, dated to 1530-1535. This one, too – Gentleman in Adoratio nby Giovanni Battista Moroni, dated 1560. Moroni’s Gentleman wears a style that I associate more with English strapwork than embroidery of Northern Italy. To some extent, these styles traveled via printed pattern books and were international.

These suggest work on the count, but possibly in satin stitch rather than double running or another linear stitch. Bernadino Luini’s Portrait of a Lady, 1525. (See. Not all early blackwork is double running!). Also this one – Romanino’s Portrait of a Man, 1516-1519. This is the picture that Marian alerted me to, starting this whole rumination. The regularity of the piece leads me to think “counted.” The angles of the ends of the leaves makes me think “satin stitch” rather than a solid filling done in another method.

This one – Portrait of a Venetian Man by Jan van Scorel (1520) looks very much like cross stitch is used to form the stitched repeat. It’s also done in red. There is no zoomable detail page for it on the website.

Of the most famous types is the inhabited style, in which outlines were infilled with all-over patterns, done on the count. My own forever project is an example of this type, although it’s my own composition and not a repro of a historical piece:

Bettes’ 1585-90 portrait of Elizabeth shows sleeves that are (at least in part) done in the inhabited style (Link via the Tudor Portraits site)

Yet another sub-style, again outlines done freehand (or drawn) rather than on the count, and accented with metal thread work. The most famous again is in a portrait by Holbein – Catherine Howard‘s cuffs, 1541. Here’s another example of freehand outlines but without the infilling geometrics: the shoulder area of Hillard’s portrait of Elizabeth I, 1575-6. Some examples of this subgroup use stippling (tiny scattered stitches) almost like pen-done line shading to provide textural or shadowed interest, or include embellishments like seed beads, pearls, or spangles.

More blackwork using colored threads? Here’s Caterina van Hemessen’s self portrait, 1548. Although tough to see, I’m pretty sure there are red cuffs and collar bands there. Red was the most popular color used after black. (I wish I could see her coif better)

There were other styles, too. All confusingly lumped together under the modern term “blackwork.”

Finally, there are portraits that show things that look vaguely familiar, but not in enough detail to be sure they are related.

- Band stitching, done in gold, with details too small to determine whether it was worked on the count – Jan Sanders van Hemessen’s Woman Wearing Gold, (undated, but the artist lived 1500-1556).

- A small collar worn by a man. Looks vaguely blackwork like, but detail isn’t very clear. Foschi’s Portrait of a Man (1530s)

- Matching(?) bands on chemises of both husband and wife. Lorenzo Lotto, 1523. Possibly freehand.

- More red blackwork? This time possibly on the collar of Charles V’s undershirt, in a piece by Bernaert van Orley, 1519-1520.

- Blackwork on edge of chemise? It’s so light as to be doubtful. Portrait of Jacquemyne Buuck, by Pieter Pourbus, dated 1551

- An all-over design produced by counted black stitching, or some sort of brocade? Hard to tell. Ambrogio de Predis Portrait of a man, dated 1500

YARDS PER MILE?

[Repost of material originally posted on 16 June 2006]

No, not a knitting-related math question (for a change), but an idle query. Check out this – a UK art student has knit hersef a car. I hope she gets a good grade on the project!

INNOVATION

Yesterday’s post got me thinking. (Always dangerous.)?

There must be tasks we wish our knitting or crocheting tools could do,

either as tweaks to existing products, or as entirely new items.

I’ve come up with several minor ones over the years. In the

spirit of Anne L. MacDonald* At the risk of compromising patentability

or re-inventing the wheel, I invite people to share ideas, and prime

the pump with some of my own.

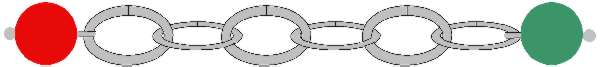

Counting Beads

I wrote about these back in my Stupid Stitch Marker Tricks

post. This is intended to be an aid for people who are

working row count repeats or those annoying "Decrease two stitches

every sixth row" directions. It’s a chain with links large enough

to admit a knitting needle, and two different color beads, one at each

end. On the first row, the knitter puts the needle into the link

closest to the green bead. On the next row (or next right side

row if working in the flat), the knitter advances the needle to the

next link, and so on. If the links are used to count pairs of

rows, a six-link chain could count 12.

Inch-Striped DPNs

I know I’ve seen photos of WWII-vintage DPNs that were striped,

but I don’t know if they were striped off in exact inch measurements

(or 2 cm for our metric friends). If I had a set of striped DPNs

I could use them to measure off length as I knit, without fumbling

around for a tape measure or ruler.

Two-Tone DPNs

This idea could be used in combo with the stripes, above. I wrote

about this one in the post remarking on a really bad answer offered up

by Lion Brand. If one had a set of similarly colored DPNs that

had a different color marking one end of each needle, one could use

that color to track where rounds began and ended. (Yes, I know

most people look for the tail, but sometimes it can be less evident,

like when you’re knitting a flat motif center out.)? The knitter

would knit all DPNs with the same color end, EXCEPT for the one that

starts off the round. That one would be employed with the

contrasting color first. If we used red and green again, we’d

knit the first needle with the green end, so that the red end was

rightmost in the work. All successive needles would be knit with

the red end. As the knitter traveled around the work he or she

would know that when a red end presented itself, that was Needle #1.

Long, Thin Sticky Notes

This one is left over from my stitching days, although I sometimes do

use sticky notes to mark my place on knitting charts. I want a pad of sticky notes

that’s six inches wide and less than an inch deep. The sticky should be

along the long edge, not at the tab end. If it had? 10 to

the inch rules on it with prominent decads, so much the better. I want to use it to

mark off the active row of an active knitting or stitching chart. Having rules on the thing would help me keep my place on the chart and if the chart’s scale was 10 to the inch – allow me to do "speed counting."

Anyone have any other innovative ideas for working tools, storage

ideas, charting aids, or other new thoughts for here-to-for unknown

tools or tweaks to existing ones?

*Anne L. MacDonald is best known for her book No Idle Hands:? The Social History of American Knitting, but she also wrote Feminine Ingenuity: How Women Inventors Changed America.

ON THE STUMP

Here’s a curious piece that came to me from the same grandparents as my fly bowl (I’ve been told that it’s actually a bee dish, not a fly bowl).

This

is an original pen and ink line drawing that appears to depict a piece

of stumpwork embroidery. It bears a sigil of the letters HCs (possibly

CCS) but has no other signature on it. It hung in my grandmother’s

library for years, and always held a certain fascination for me when I

was a kid. At that time I didn’t realize the embroidery connection. At

seven I liked the whimsical little animals in the corners, and the fact

the central figure was a queen. Anecdotal family tales say the title of

this piece is "Queen Esther."

Years later when I began

embroidering in earnest (started on that path by the same grandmother),

I stumbled across the stumpwork style and recognized the drawing for

what it was. I’m torn. I’m not exactly sure if this is a copy of a

piece displayed in a museum, or if it’s a freehand drawing inspired by

that style. I rather suspect the former. There is supposed to be a

stumpwork piece depicting Queen Esther n the

collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society, but I haven’t seen

a picture of it, so I can’t say if my pen and ink drawing shows that

particular artifact.

Stumpwork

(raised or embossed embroidery) was popular in the 1600s, tailing off

into the early 1700s. It has enjoyed a couple of minor revivals since.

It’s characterized by three dimensional effects, and is gaining

interest right now, in part fueled by the popularity of ribbon

embroidery and Brazilian embroidery, two other more modern styles that

also employ three dimensional effects. There are also traditional

forms of padded stitching practiced in Thailand and Cambodia that also

use heavy stitching on separately embroidered motifs that are affixed

to a ground over stuffing.

In stumpwork, much of the

stitching is done over raised grounds, separately stitched and sewn

onto a backing fabric. These motifs and slips are stuffed

underneath with batting or even little wooden forms. Additional raised

effect is provided by the inclusion of detached stitching, much of it

based on detached buttonhole, hollie point, or other "free" lace

stitches. On some pieces, further embellishment is provided by the

liberal use of gold and silver threads, sequins, spangles and even

beads. Some say that the little wooden forms used for stuffing

are the "stumps" that gave the work its ungraceful name, others say

that the name is a corruption of the word stamp, as many of the faces

of the figures were printed by stamping rather than being stitched.

It’s heavy and encrusted looking except in its very lightest

manifestations, not well suited for wearing. Instead it was employed

mostly for decor – panels, mirror surrounds, book covers, cushions, and

most especially small chests (cabinets) that were covered inside and out with the stitching.

Creating

a cabinet was a crowning glory for the amateur needleworker of the late

1600s. They were expensive to do, required better than average skill,

and represented a sort of needlework "graduation" for teens just about

done with the course of informal study that passed for most girls’

educations at that time.

There are several articles on stumpwork available elsewhere on the web, but precious few pictures of historical examples: This one has a useful bibliography, Janet Davies has some photos of artifacts that show the dimensionality of the stitching on her stumpwork and raised Elizabethan embroidery pages, CameoRoze also offers up an article on the modern revival of the style. In a Minute Ago also offers up a nice round-up of stumpwork and related styles as they are practiced today.

In the mean time my Not Embroidery hangs in my bedroom, where it complements a larger blackwork panel.

ONE STITCH = THREE FEET

I was out webwalking again and came upon this:

It’s a report of a bit of performance art/industrial control/knitting

that boggles the mind. The artist is directing the production of

a knit US flag, using aluminum street light poles as needles and giant

strips of felt for yarn. The actual knitting was performed by two

John Deere excavators, handled with amazing delicacy and

precision. The image is from a story on iBerkshires.com, reporting about the event which took place at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art.

The artist in question is David Cole.

This isn’t the first exploration of knitting (giant or human scale)

he’s done. He’s also done a previous bit of oversize knitting

with construction machinery, working up fiberglass insulation into a

giant slouchy teddy bear. His other works can be seen at his

website.

I can’t say that the gauge of the flag was in fact 1 st=3 feet, but one

has to admit that it’s pretty huge. I’m especially boggled at the

thought of someone deconstructing the movements to produce a knitting

stitch, then reproducing that series behavior using the controls of the

excavators. I’d love to applaud not only Mr. Cole (for his

imagination in thinking up this concept), but also the equipment

operators. "Knit a flag" is an incredible thing to put on one’s

equipment resume, and is quite a testament to their skill.