FUN WITH ODONATA

UPDATE: THIS DESIGN IS NOW AVAILABLE AS AN EASY TO PRINT PDF DOWNLOAD UNDER THE EMBROIDERY PATTERNS LINK, ABOVE.

A short post today on a time-stressed weekend day.

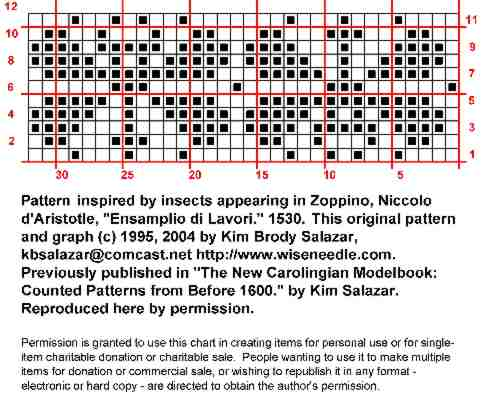

Buzzing in on the hopping heels of last week’s bunny, here’s another small graph from my embroidery book. This super-simple one is original. One dragonfly can be spot-placed, or they can be done in series using stranding. A strip of dragonflies can bealigned either katywumpus as I show here, or all facing the in same direction. In knitting, I think that these would be particularly fun to accent with shiny beads or duplicate stitching on the body or wings. They’d also be a killer trim if done in bead knitting.

Other uses for simple graphs include filet crochet (Mary Thomas’ Knitting Book describes filet knitting, too); all types of cross stitching; needlepoint; and lacis or pattern darning. I’ve even heard from people using TNCM patterns for wood marquetry and tile mosaics!

FUN WITH LAGOMORPHS

UPDATE: THIS DESIGN IS AVAILABLE ON THE EMBROIDERY PATTERNS LINK ABOVE, IN EASY-TO-PRINT PDF FORMAT.

SECOND UPDATE:

The source for this is under re-evaluation. I’ve found it in Bernhard Jobin’s New kuenstlichs Modelbuch von allerhand artlichen und gerechten Moedeln auff der Laden zuwircken oder mit der Zopffnot Creutz und Judenstich und anderer gewonlicher weisz zumachen, published in 1596. I believe that when I first transcribed this from microfiche in the early ’70s there was a mixup in the labeling of the fiches I consulted. If TNCM gets reissued, I will insert the correction.

I was re-graphing this rabbit from my book of embroidery patterns, and I thought angora-fanciers might like to work it into a headband or sweater front.

The original plate from 1597 showed a large group of animal motifs clustered together to save space. It included this one, two coursing dogs (possibly greyhounds) a squirrel, an owl, a stag, a unicorn,a parrot, a yale, and the lion I previously shared for Gryffindor pullovers.

PROJECT – DOUBLE KNIT HAT GRAPH

Again apologies to those on the updates mailing list. I did a bit more maintenance, adding categories to all the existing posts so it’s easier to page through this ever-growing mound.

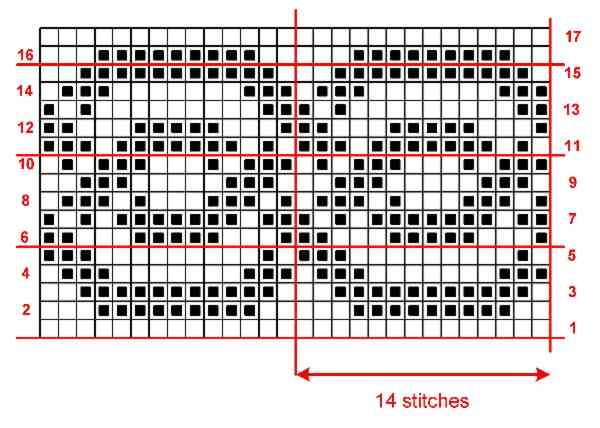

A couple of people have asked for the graph I used to knit the interlace shown on my overly warm teal and black alpaca hat. Here it is.

This one didn’t make the cut for my book because it’s one of the designs for which I lost my notes. A long time ago I had a miserable move between apartments. Several boxes were stolen off the back of my truck. Among the things that went missing was a notebook full of source notations for counted embroidery patterns. I had been researching them casually for more than ten years, and had hundreds compiled. The sketches for most of them had already been redone on my ancient Macintosh, but all associated notes remained solely on paper.

When I was composing The New Carolingian Modelbook I had to go back and confirm the exact origins for all the counted patterns I wanted to include. I managed to find the sources for about 200 of them, but a third as many more have eluded me. This particular interlace is from my collection of the lost. It is similar to designs by Matteo Pagano as published in his 1546 book Il Specio di Penfieri Dell Berlle et Virtuoise Donne, but I can’t swear that it came from that or one of his other works. Given the relatively clumsy, heavy spacing and short repeat it might even have been something I doodled up myself after a day of research.

Many of these early Modelbook designs got there by way of Islamic influences (especially patterns cribbed from woven carpets and embroidered textiles). Over the years the patterns drifted away from work worn by the elite to work worn by middle and then lower social classes, eventually ending up in folk embroidery where they never quite died out. Counted thread needlework styles were revived big-time among the fashionable in the mid 1800s. Researchers found and reproduced surviving older pattern books, and began collecting motifs from traditional regional costumes and house linen. Some of the later and folk uses of counted patterns include standard cross-stitch, Hedebo, Assisi-style voided ground stitching, and various types of pattern darning or straight stitch embroidery done on the count.

This pattern can be interpreted in many crafts. Historically accurate uses contemporary with first publication include cross stitch panels (the long-armed style of cross stitch is overwhelmingly represented in historical samples compared to the more familiar x-style cross stitch); weaving, or lacis and burato (types of darned needle lace).

Counted patterns are a natural for knitting. The first book of general purpose graphed designs that listed knitting as a specific use came out in 1676 in Nurnberg, Germany and was published by a woman: Rosina Helena Furst’s Model-Buchs Dritter Theil. (the title is actually much longer). There may be others that predate this book, but I haven’t seen mention of them, and I haven’t seen the Furst book in person. It’s in the Danske Kuntsindustrimuseum in Copenhagen, a tad far for a day trip from Boston, Massachusetts. The entire group of graphed designs displayed in the early Modelbooks shows a straight continuity with the geometric strip patterns found in modern northern European stranded knitting.

The short 14-stitch/17 row repeat of this graph does work well at knitting gauges. I’ve always meant to use this one again on socks -either as-is or stretching it a bit by repeating the centermost column so that it better fits my sock repeat, or doing eight full repeats at an absurdly tiny gauge. As is, you’d need a multiple of 14 stitches around. A standard 56-stitch sock could accommodate 4 full iterations of the design without adding any columns.

Some people have asked how to get a hold of my book. The answer is, aside from the used market where it is going for quite a premium, I haven’t a clue. Sadly all I can report is that the publishers absconded shortly after publication. I have no idea where they went, and have had no replies from them to any queries since 1996. I received only about a year of royalties on the first 100 or so copies, in spite of the fact that the book went through at least two printings with an estimated total run of 3,000. New copies continue to trickle onto the market even today (they’re sold as used but mint). The new-copy seller has rebuffed my attempts to find the ultimate source.

Moral of the story – don’t enter into publication contracts without a literary agent, and if the company has a name like “Outlaw Press” there’s probably a reason.