A SUPPORTING CAST OF GRIFFINS

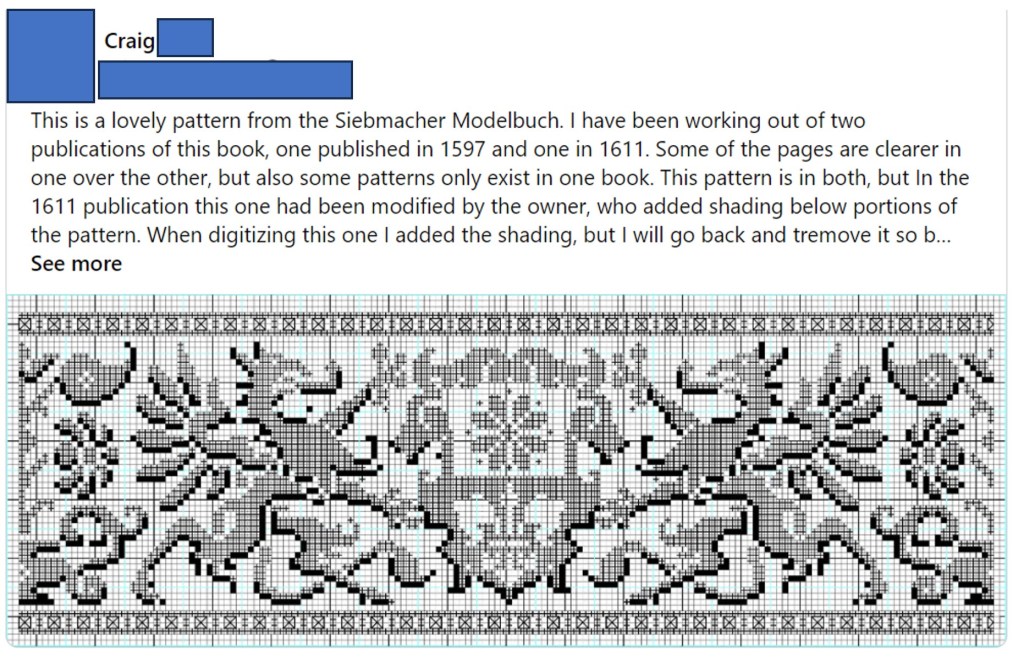

Friend Craig posted a memory last week, and re-shared a chart he adapted from one of the Siebmacher modelbooks – from the 1611 edition.

It got me to thinking. Those heraldic style charted bands appear over many years, and in several iterations. It might be fun to see how they assorted over time. So I went hunting. I combed through my notes, the Internet Archive’s collection of modelbook images, and several other sources.

This isn’t an exhaustive analysis, but it covers most of the easily accessible editions of the chart. And the large number unearthed really underscores the differences in that accessibility from the time I started poking into these early publications (circa 1974) to today. Back then there might be a couple of modelbooks as part of a microfiched set of early publications on file at one’s university. There were several sets of these ‘fiches scattered across the country, so the set that was local to me at Brandeis wasn’t necessarily the same as the set someone else might have at the University of Pennsylvania. A happy trade of blurry low quality photocopies ensued among us needlework dilettantes, and in some cases precision in attribution wasn’t as clear as it could have been. As a result, when I get around to reissuing The New Carolingian Modelbook, my first book of researched patterns, there will be corrections. Especially among the Siebmacher attributions, because somewhere along the way prints from several editions became confused, leading to a couple of the designs marked as being from the 1597 edition, actually being from a later printing.

And Siebmacher or Sibmacher – both actually. I haven’t a clue as to which spelling is the correct one, because both are used. IE is represented more often than just I, so I go with that.

So here we go. It’s another overly long post only a needlework nerd will love.

1597

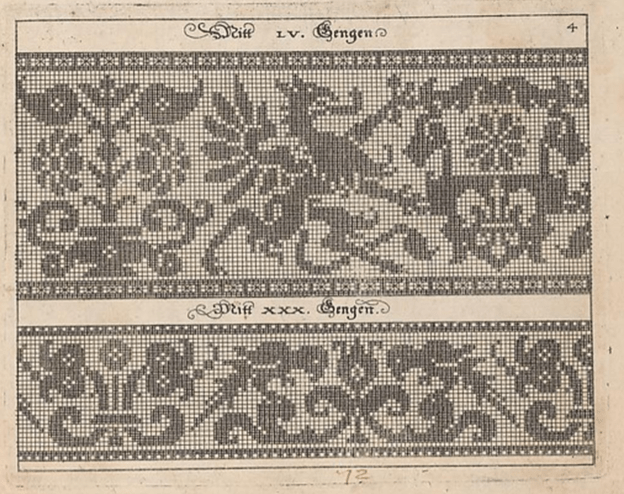

Johann Siebmacher’s Schon Neues Modelbuch von allerley lustigen Modeln naczunehen, zuwürcken unn zusticken, gemacht im Jar Ch. 1597. Printed in Nurmburg.

This edition is held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accession 20.16 and can be accessed here. Notes accompanying this edition cite that the modelbook historian Arthur Lotz cataloged two editions were printed in 1597, and this is from the later of the two. (I will try to fill in the Lotz numbers for these as I mention them. I have that book, but I don’t read German so please forgive my tentative attributions.) My guess is that this one is from Lotz 32b.

Note that it presented on the same page as the parrot strip. The numeral LV (55) at the top refers to the number of units tall the strip is. Note that all filled blocks are depicted in the same way – as being inhabited by little + symbols. There is also a companion border that shows a combo of filled boxes and straight stitches. Also note that the two “reflection points of the repeat are both shown, along with enough of the repeat reversed to indicate that the design should be worked mirrored. Craig got this spot on when he drafted the design for himself. I’m used to working straight from the historical charts but most folk find the mental flip a bit arduous. He wisely spared himself the conceptual gymnastics.

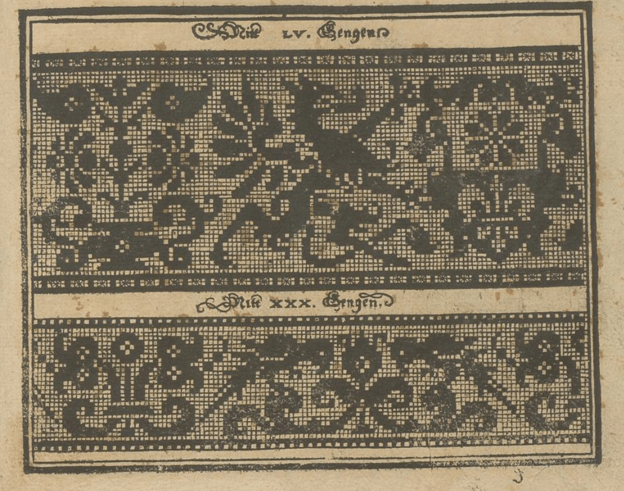

Johann Siebmacher’s Schon Neues Modelbuch von allerley lustigen Modeln naczunehen, zuwürcken unn zusticken, gemacht im Jar Ch. 1597. Printed in Nurmberg.

Here is the same page from the other edition of 1597. Very possibly Lotz 32a. It’s held by the Bayerische Stasts Bibliothek, and is shared on line here.

It’s very clear that these are both impressions from the same block. The inking is a bit heavier on this one than the other, but the design is the same. Note though that the little “4” in the upper right corner isn’t shown on this one.

The Bibliotheque nationale de France’s copy of Johann Siebmacher’s Schön Neues Modelbuch von allerley lustigen Mödeln naczunehen, zuwürcken unn zusticken : gemacht im Jar Ch. 1597 looks like it might be the same printing as the Lotz 32b version above. It has the same “4” in the corner. BUT throughout the book it appears that someone has added shadings and color variation indicators by hand – over-inking or penciling in selected areas of many of the patterns. I don’t know if this was done by an owner, or was sold this way. I suspect the former. The darker boxes are clearly produced by careful inking, not printing. In other pages of this edition, you can see differences in how thick the ink was laid on, following pen or brush stroke lines, and not imprinted.

I don’t see a date associated with this other annotated edition, listed only as Johann Siebmacher, Newes Modelbuch, but I suspect it’s the 1597 one based on plate similarities. It’s another book in the Clark Art Institute library. Again someone took the liberty of hand-inking some of the pattern pages to add additional shading or interest. You can view it here. Given the placement of the shading, it might be the source for the version Carl used when he drew up his own graph.

Additional reprintings.

I’ll spare you more echoes of exactly the same page, but here are other representations of these 1597 editions.

There was a reproduction made in 1877, called Hans Sibmacher’s Stick- und spitzen-musterbuch: Mit einem vorworte, titelblatt und 35 musterblattern. The editor was Gerold Wien, and it was put out by the Museum fur Kunst und Industrie. The plate is a duplicate of the Lotz 32b one, complete with the 4 in the upper corner. The date of the original is cited in the repro. You can see it here. A second copy of the 1877 facsimile edition is held by the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek and can be found here.

There is an additional reproduction of this book in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art, as issued in Berlin in 1885. The image quality is excellent, you can find it here.

1599

Martin Jost. Schön Neues Modelbuch von allerley lustigen Mödeln naazunehen Zuwürken vn[d] Zusticke[n]: gemacht im Jar Ch: 1599. Printed in Basel.

Yes, a different name is on this book. Lotz 34 refers to it by the name of the publisher – Ludwig Konig in Basel. The on line listing also mentions Jost. It is very closely related to the works above with lots of designs in common. But not entirely the same. The on line copy is here.

That’s our friend the griffin, the same motifs on the shield being supported, and the same flower pot behind – all absolutely stitch for stitch true to the earlier version. But the repeat is truncated along the left edge. The left side of the flowerpot is gone. However the upper and lower companion border with its straight stitching is the same, and is aligned the same way with the main motif. Obviously the parrots are gone, replaced with a panel representative of cutwork. The words above the design are the same font size and typeface, but are now centered between the new borders. The letters have the same proportional size to the design’s block units, but the block units are now rendered as solid – not boxed crosses. These books are said to be among the first created using copperplate – not carved wood. I am not familiar with the process of creating those, but it does look like a print of the original might have been used to create this smaller version. Licensed reproduction, cooperative venture, or unauthorized knock-off? I am sure there are academics who have explored this, so I won’t let my speculation run wild.

Additional appearances.

There is another copy of this same griffin imprint in a book cited as Ludwig Kunigs Fewrnew Modelbuch, von allerhandt künstlicher Arbeidt: namlich gestrickt, aussgezogen, aussgeschhnitten, gewiefflet, gestickt, gewirckt, und geneyt : von Wollen, Garn, Faden, oder Seyden : auff der Laden, und sonderlich auff der Ramen : Jetzt erstmals in Teutschlandt an Tag gebracht, zu Ehren und Glücklicher Zeitvertreibung allen dugendsamer Frawen, und Jungfrawen, Nächerinen, auch allen andern, so lust zu solcher künstlicher Arbeit haben, sehr dienstlich. Printed in Basel, 1599. You can find it here.

The Lotz number for this one is 35. It’s a problematic work because it looks like at some point a bunch of pages from several different pattern books were bound together into a “Franken-edition” incorporating some of Pagano, Vincoiolo, and Vecellio in addition to the Siebmacher-derived pages. But the solid blocks griffin with the cut off flower vase, plus the cutwork panel below is identical to the other 1599 imprint.

Jost might have been a bit peripatetic. There is an identical impression of this version in another Jost Martin printing, Schön neues Modelbuch von allerley lustigen Mödeln nachzunehen, zuwürcken un[n] zusticke[n], gemacht im Jar Chr: 1599, printed in Strassburg. No differences from the one above, so I won’t repeat. Possibly the same Lotz number, too. But you can visit it if you like.

1601

Georg Beatus, Schon neues Modelbuch, printed in Frankfurt, 1601.

Yup. Another publisher. This copy is Lotz #40, and is held in the Clark Art Institute Library. You can see it here.

This print looks a lot like the Jost/Konig one, but not exactly so. First, you can dismiss those little white dots. Those are pinpricks, added by someone who ticked off the solid units as they counted. I deduce that because they are also present in many of the empty boxes. But you will notice some oddities. First, the design is further truncated at the right. We’ve lost the complete shield shape bearing the quaternary flower. And the column at the far left has been duplicated. There is also an imprecision on column and row width in this representation, absent on the others. Finally, it’s been formatted for a single print, with no supplemental design below. I’m guessing another plate.

1604

Johann Siebmacher. Newes Modelbuch in Kupffer gemacht, darinen aller hand Arth newer Model von dun, mittel vnd dick aussgeschneidener Arbeit auch andern kunstlichen Neh werck zu gebrauchen. Printed in Nurmberg, in 1604, in the shop of Balthasar Caimox. It’s in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, accession 29.59.3, and can be seen here. I don’t see this one listed in Lotz under 1604, but the Met’s listing says that it’s likely a re-issue of the 1602 edition which would make it one of the ones Lotz labels as 38a through 38e. What’s notable about this particular copy is that while many of the other fabulous animal/mythical creature strips that accompany the griffins page in the other works, the griffin page itself is missing. It wasn’t in this edition, or the page that bore it has been lost to time. I’ve included this citation here for the sake of completeness.

Note also that this 1604 edition is the one upon which the modern Dover reprint is based. Dover reissued Ernst Wasmuth’s 1880 publication, which he entitled Kreuzstich-Muster 36 Tafeln der Ausgabe v. 1604. That was based on 36 plates from this 1604 printing.

1607

Sigmund Latomus, Schön newes Modelbuch, Von hundert vnd achtzig schönen kunstreichen vnd gerechten Modeln, Teutsche vnd Welsche, welche auff mancherley Art konnen geneet werden, als mit Zopffnath, Creutz vnnd Judenstich, auch auff Laden zu wircken : Dessgleichen von ausserlesenen Zinnigen oder Spitzen. Allen Seydenstickern, Modelwirckerin, Naderin, vnd solcher Arbeitgefiissenen Weibsbildern sehr dienstlich, vnd zu andern Mustern anleytlich vnd verstendig. Printed in Frankfurt, 1607.

Yes, another name on the spine, and printed in another city. The copy from the National Library of Sweden is visible here. It’s cited as being Lotz 43b.

At first glance this looks like another imprint of the same Siebmacher griffins and parrots page from 1597, but look closer. This design adds a blank column of squares to the right edge, replacing the design elements that were there on the earlier block. This is especially evident in the parrot strip, which has lost its center reflection point along the right edge. Also the blocks are filled in, again not the boxed crosses of the earlier work. And the fills look printed, not applied (more on this later). Yet another plate? Not impossible.

1622

Sigismund Latomus was still active in 1622, issuing a modelbook, entitled Schön newes Modelbuch, von 540. schönen auszerwehlten Künstlichen, so wol Italiänischen, Französischen, Ni-derländischen, Engelländischen, als Teutschen Mödeln, in Frankfurt. As one would expect from the lengthy name, he swept up a number of pattern images, issuing them in one big bundle. Of course we can’t rule out that what we see isn’t the original document as published. It’s not at all uncommon for later owners to bind works together (binding was expensive, and separate from publishing).

Our griffins are in this collection, TWICE. One version is another imprint the same rather squished version we saw issued by Beatus in 1601, the other is one we haven’t seen before. It’s roughly similar to the one above it, but there are some very subtle differences in detail, especially along the left and right edge. And of course, it’s paired with yet another secondary border. Original inclusion, or the result of later co-binding? Your guess is as good as mine. The book is here, it’s in the Clark Art Institute Library’s collection.

1660

Skip forward even further, now 63 years since the griffins appeared. Rosina Helena Furst/Paul Furst’s Model Buch Teil.1-2 printed in Nurnberg in 1660 offered a collection of older designs in addition to new ones. There were four in his series. This particular binding combines books 1 and 2. Lotz cites volumes one and 2 as 59 and 60, each with multiple surviving copies. For what it’s worth the Furst books are the first one that mention knitting as a possible mode of use for graphed patterns, and very possibly the first that is credited either in whole or in part to a female author. Some sources credit Paul Furst as the publisher and Rosina Helena Furst as the author, others attribute the entire work to Paul, or imply that Rosina Helena took over the family business after Paul’s death. In any case, they were prolific publishers, and continued to revise, and re-release modelbooks for at least a good 20 years. They did recast the legacy images to meet changing tastes, but it’s clear that our griffin has deeply informed this later, slightly more graceful beast. Note that his pattern height number is different from the earlier ones because his spacing and borders are a different size. You can see this copy here.

1666

We continue on with the Furst Das Neue Modelbuch editions. This one is also from Nurnberg, and is a multi-volume set in the care of the Clark Art Institute Library. The parts are listed as Lotz 59b, 60a, 61b, and 62a. Again someone has inked in bits to indicate shading. But it’s clearly the same plate as the 1660 printing.

1728

This is about as late as I research. Here we are 131 years after first publication, and there is still interest in the griffins. At least in the Furst interpretation of them. This is from the workshop of J.C. Seigels Wittib, in Nurnberg, and is a reissue of the Fursts’ Model Buch Teil 1-2. Again from the Clark Art Institute Library. It also looks to have been hand-inked on top of the same plate print. But if one looks very closely, there are small mistakes in ink application with very slight differences between the two. Including a forgotten square that shows the + behind the ink in one and not the other. A clear indication that the solid black areas were additions, and not done during the print process. It also makes me think that the 1728 inker had a copy of the 1666 book and copied the annotations to the best of their ability. Does that mean that some books were sold pre-inked? Not impossible. You can make your own judgement here.

Stitched representations

I am still looking for these. Representations of other Siebmacher designs exist in monochrome and polychrome counted stitching, as well as in white openwork. His reclining stag is the most often seen through time, but his unicorns, peacocks, eagles, religious symbols, long neck swans, flower pots, and rampant lions grace some spot samplers of the 1600s and into the early 1700s – mostly but not exclusively German or Dutch in origin. I’ve seen the parrots, undines, and mermen in white darned pieces (lacis in addition to withdrawn thread darned work). And that reclining stag crossed the ocean to appear on some early American samplers as well. But I haven’t seen a stitched version of these griffins. Yet.

Of course I haven’t seen everything, and back room pieces are being digitized every day. If you’ve spotted the griffins in the wild, please let me know.

Conclusions

This really is more of an observational survey than an academic hypothesis based essay.

Originally, seeing this (and other Siebmacher designs) repeat across multiple modelbooks, I assumed that they all were produced from the same plate. But on closer examination we see that probably isn’t true.

It is safe to say that there is a strong continuity of design here. And an interesting cross pollination among publishers. Was it tribute, licensing, sharing, or a bit of light plagiarism? We cannot tell from just examining the printings. But we can say that over the course of 131 years there were at least four and possibly five plates made based on the original griffin design, yet all are immediately identifiable as springing from the same source. I’m sure there are scholars who have delved into the interrelationships in the early printing industry, and have described other migrations of text or illustration among printing houses. Perhaps this look at a single pattern book plate will help inform their future musings.

We can also say that these design plates were used by a variety of prolific printers in Germany in response to what must have been continuing demand for pattern books. I say that because they were obviously selling well enough to warrant production over a long span of time, in spite of their largely offering up the same content over and over with only minor supplements. Also, in spite of the sometimes destructive nature of pattern replication at the time these early pattern books survived largely (but not totally) intact. For something so esoteric, with little literary value, they were seen as interesting and useful enough to retain in many libraries – to the delight of those who have rediscovered them again and again across centuries.

I just might have to stitch up these griffins, and in doing so know I’m helping to keep them alive.

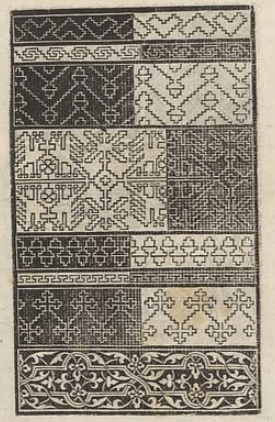

MODELBOOK BLOCKS: ACORNS AND CHICKENS

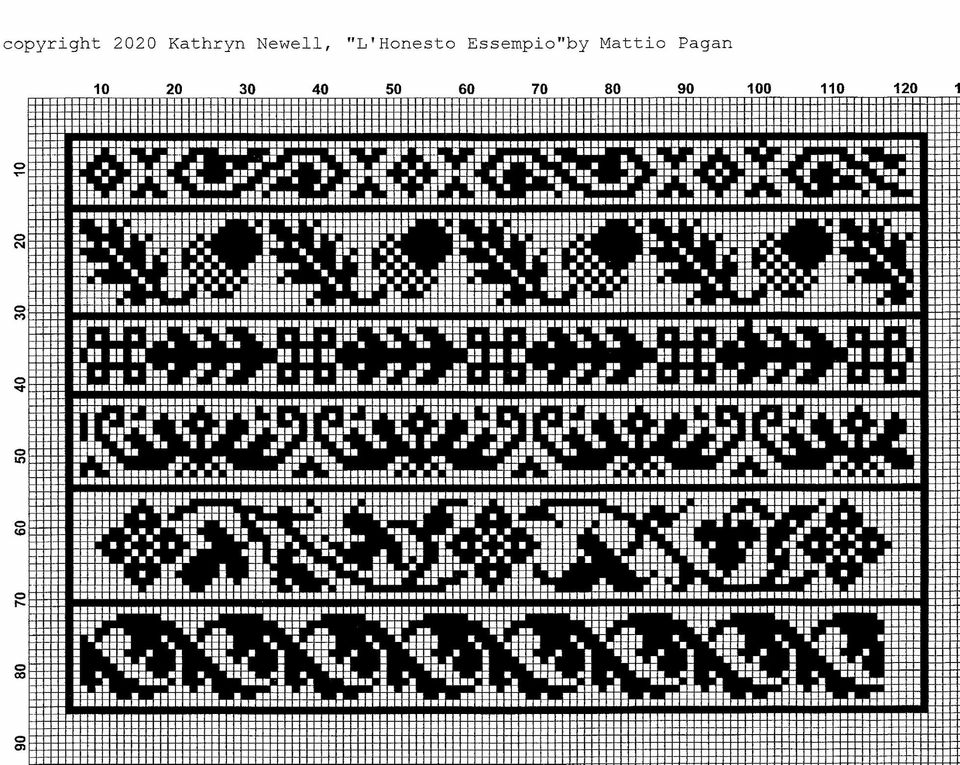

Long time SCA friend/needlework penpal and costuming/stitch research role model Kathryn Goodwyn recently began posting her transcriptions of charted modelbook pages she’s collected over the years. She’s in the middle of a series from Matteo Pagan’s L’Honesto Essampio del Uertuoso Desiderio che hano le done di nobil ingegno, circa lo imparare i punti tagliati a fogliami, published in 1550, in Venice.

This is her chart of one of the pages, presented here with her express permission:

In her post to the Historic Hand Embroidery group on Facebook, Kathryn noted that in the original, there was something odd with the acorn panel – that the count inside the frame didn’t match that of the other strips that accompanied it. Lively discussion ensued. Some people opined that the strips were all cut on individual blocks, assembled into a page at the time of printing, and pointed to the large number of designs that appear in multiple books over time, put out by different publishers.

I agree that there was lively trade and outright reproduction (authorized or not) in early pattern books. There are many instances of designs appearing either verbatim (probably printed from the same blocks), and being re-carved with introduced errors and minute differences. And it makes perfect sense that in the high precision work of block production, carving separate strips would be more forgiving of errors. If a chisel slips, only one design would be spoiled – not the entire page.

However in this particular instance, I think that this piece was carved as a single, integral block. And the skew count for Acorns was a kludge, done when the carver realized that the design would merge into the border of the block and took pains to nibble one last partial-width narrow blank row from the wide border, to separate the leaf from it.

I have found two (possibly three) renditions of this page, all from various extant Pagano volumes.

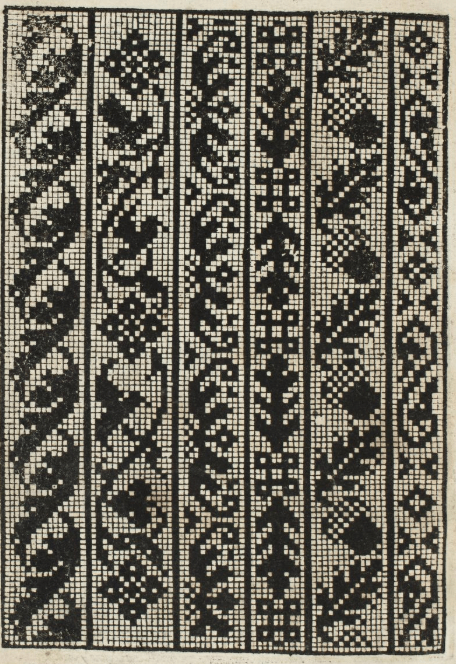

From the L’Honesto volume (1550) held by the Sterling and France Clark Art Institute Library, available on Archive.Org:

Sadly the edition of L’Honesto in the Gallica collection in France (dated 1553) does not contain this page, but modelbooks were probably issued as folios rather than bound volumes (buyers later paid to have them bound, and decades could have elapsed before that happened), experienced hard wear, and it’s not unlikely that this one is only partial.

The plate however shows up again in a composed edition of Pagano’s later work, La Gloria et L’Honore di Point Tagliati, E Ponti In Aere (1556) now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum in New York (Accession 21.59.1). There is some confusion in the museum’s presentation – it’s not clear if this page is included once or twice. There are two images of it each tagged with a different page number, plus one image with no page number tag. On all three the facing pages are identical, as are tiny print imperfections on the pictured plate; which leads me to suspect that (gasp) there is a mistake somewhere in the museum’s on-line listings:

- The link for the first image below.

- Link for the second image below.

- Link for the third image below.

I have found this plate and its constituent strips ONLY in these images. I have not found the plate as a whole in another work, nor have I found these exact strips (identifying mistakes and all) replicated in combo with other strips in other Pagano works, or in issues by Vavassore (a close associate).

However other designs do appear to wander. Or do they…..

I’ve noted a couple of these before – but those tended to be full page designs. How about clear instances where a page of designs was created from constituent individual blocks, and those specific blocks can be spotted in different compositions/pages?

It’s surprisingly difficult to find evidence of independent re-use of identifiable single-strip or single motif blocks. Even for a very recognizable and common design that at first glance looks like a single block that wandered among several pages.

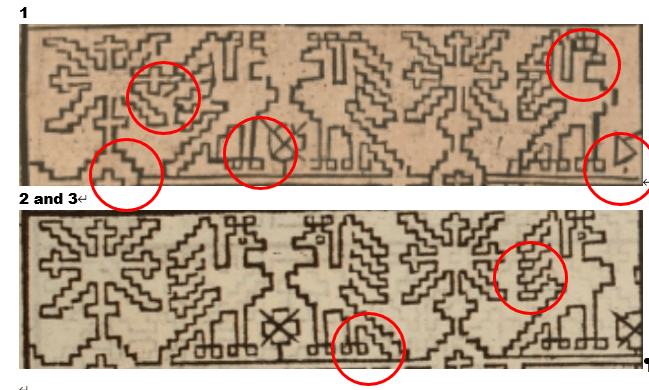

Here’s a well represented one. The Chicken Page. (My own shorthand name for it, nothing actually official.) This design shows up again and again, and persists over the ages in folk embroidery styles of Sicily, the Greek Islands, and up through Eastern Europe and into Russia. It’s meant to be rendered in double running (or back stitch) and in modelbooks often appears with other designs of similar technique on the same page. For a very long time I thought there was only one chicken. But not so.

The copy on the left below is the chicken page from Quentell’s Ein New kunstlich Modelbuch, Cologne, 1541. (I normed these pages to the same orientation for easier comparison.) The middle copy is from Ein new kunslich Modelbuch dair yn meir dan Sechunderet figurenn monster… published in 1536 in Koln, by Anton Woensam. It’s also in Ein new kuntslich Modelbuoch…,attributed to Hermann Guifferich, with a hard date of 1545 (the same page is also in his Modelbuch new aller art nehens und stickens, from 1553). On the right is an example from the composed volume La fleur des patrons de lingerie – an omnibus volume that contains four different modelbook editions bound together. While the archive lists 1515 as the publication for La fleur, that’s not correct.

Some more. At left is the Chicken Page from Zoppino’s Ensamplario di Lavori of 1530, in the version cleaned up and presented as Volume I of Kathryn’s Flowers of the the Needle collection. On the right is another imprint of the same exact block or set of blocks, from Pagano’s Trionfo di Virtu, of 1563.

Obviously the second set of chicken images was printed from exactly the same full page block, in spite of being both the earliest and the latest example in our total set. There are no deviations, and all copyist’s errors are the same, left and right for every strip. However they are also clearly not printed from the same blocks others. Most obviously, the chicken repeat in the set of two doesn’t begin or end at the same point as it does in the first set of three.

But I don’t think all three chicken panels in the first set came from the same nest either. There are too many differences between the first shown panel and the other two next to it. Not just partial lines where ink may not have reached during the print, but actual deviations in the carving:

The other strips on the leftmost example of the three also deviate from the other two examples in its set, elongated stitches represented, different numbers of counts in comparable stepwise sections and the like.

My conclusion from this flock of chickens is our bird motif was carved three times. One imprint appears in Quentell [Chix1]. A second is in Woensam/Guifferich/[La fleur] [Chix2]. And a third appears in Zoppino/Pagano [Chix3].

Our timeline is now something like:

- 1530 – Zoppino – Chix3

- 1536 – Woensam – Chix2

- 1541 – Quentel – Chix1

- 1545 – Guifferich – Chix2

- 1553 – Guifferich – Chix2

- 1567 – Pagano – Chix3

What we are NOT seeing in this ONE particular case is that the chicken motif although quite prevalent and highly mobile was NOT being re-used as a single block, in combination with assorted blocks to make unique pages. Instead it appears with its established companion set – verbatim. And in the instances where it looks like it might be nesting with new friends, it is in fact an entirely different carving – a totally different chicken.

Finally, I am not sure why the positive/negative presentation is so prevalent for this particular style of block. My guess is because the dark lines/light ground carving was fragile and more time-consuming to produce than the dark ground white lines areas. Perhaps the dark areas were an economy measure, or their presence strengthened the block as a whole so that it lasted longer or warped less (dark/light areas on these blocks tend to alternate left/right).

Apologies for the length of this post. If folk remain interested I’ll look at the peregrinations of other specific designs.