A BUSY JUNE SO FAR

Who said that retirement would be boring? Wrong, wrong, wrong.

We’ve spent the last month quite busy, buzzing back and forth to the Cape to escape the heat and enjoy the late pre-season quiet of the beach. We’ve kept at the garden I detailed in the last post. So far everything is surviving. Bushes and flowers bloomed and my tiny raised bed garden is beginning to offer up a small, but appreciated harvest of peppers and herbs. The eggplant will catch up eventually. And of course I’ve been doing needlework projects. The chair recover is in hiatus until the fall – too much infrastructure to schlep around, but smaller, portable projects have been thriving.

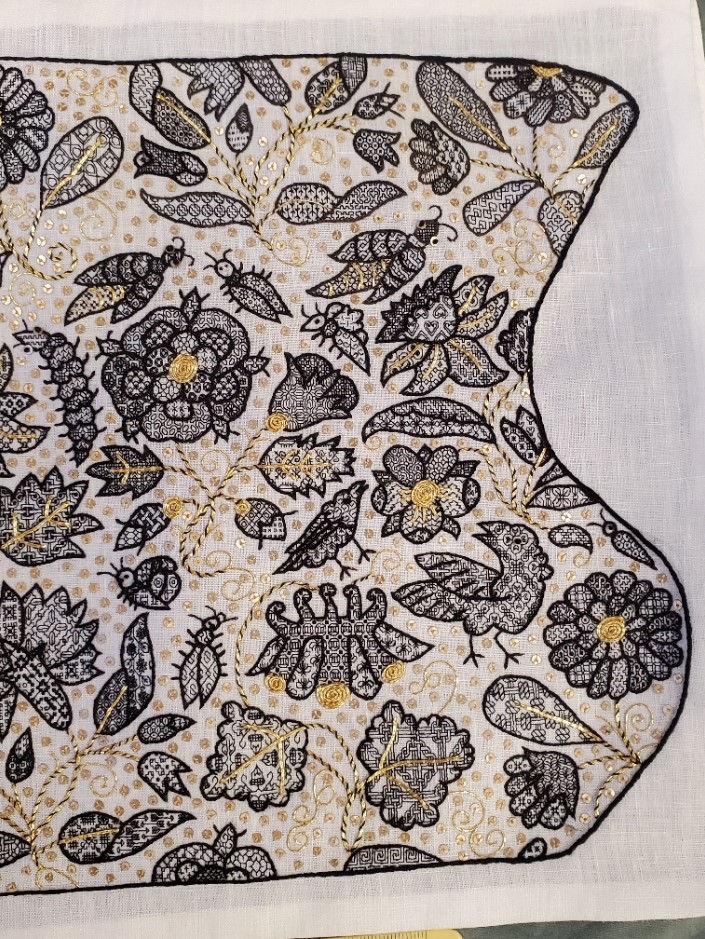

First up, a stitching finish on a WIP that’s been bopping around since before the Unstitched Coif. This is a forehead cloth, in more modern terms – a kerchief. I had made two some years back, and have loved them to pieces. The stitched body of each is still in perfect shape, but the ties on them have died. Here is the new one, not yet assembled into final, wearable form.

This is a doodle of a pattern that will be in Ensamplario Atlantio Volume III. I’ve been working on that, too and have about 20 plates of new fills. I’m planning on including several pages of larger patterns, strips, and even yokes, too. I am still dithering about including the free patterns that make up my Epic Fandom Stitch Along in it, too. It’s already a wildly anachronistic work, and it might be handy to have all that content in one place. In any case, EnsAtl III is very much a work in progress, and will be out as soon as I can manage it.

Back to this piece. It’s an experiment. I wanted to try out Sulky 30, a spooled thread sold for hand and machine embroidery. I’m working on 32 count linen, and two strands of the Sulky work nicely in terms of coverage and line depth. There are four colors here – an almost-cranberry red, a forest green, a navy blue, and (hard to see) small motifs filling problem spaces, worked in black. There are LOTS of mistakes in this. Places I missed a stitch, or substituted the wrong twist or size center flower, but since this is a quick stitch, meant to be worn to death and not a future heirloom of my house, I didn’t bother to go back and pick them out. I did fix mistakes that would have thrown off the design as a whole, though.

My thoughts on the Sulky? Not my favorite. It’s very hard twist and dense. While that makes a nice, clean line, it does make intersections a bit more difficult to keep even. Plus when picked out, both the blue and the green crock a bit – leaving color residue on the cloth independent of fiber crumbs. I’ll probably use up what I have on things I intend to wash savagely, but I won’t be buying more. The Unstitched Coif project spoiled me. Silk over cotton, any day.

I can’t report on the origin of the ground. It’s a scrap left over from something else. A garment has been cut from it. I did get a pile of linen scraps from someone here in town, via one of the local waste-nothing exchange groups. I’m pretty sure this was one of the pieces. So my guess is that it was yard goods, not custom-sold for needlework. Even so, the count is remarkably even. There’s some slubbing but not overly much, and the thread count is something like 32×33 threads. No selvedge left so I can’t guess about warp vs weft counts.

I am going to investigate narrow twill tape for the ties this time – both for this forehead cloth and to replace the now frayed and ruined ties of the older two. I had used the ground itself, double folded and seamed for the ties on the old one. Better I should use something more densely woven and robust, and that can be easily replaced.

I’ve also been knitting and crocheting. Here are July’s socks. Not sure what made me knit the wide-stripe pair so tightly, but I did. They are the same stitch count around as the other pair, but are significantly narrower. I can wear them (just), but not all of my target audience can. So they will either stay home with me or find a narrow footed new friend with whom to play.

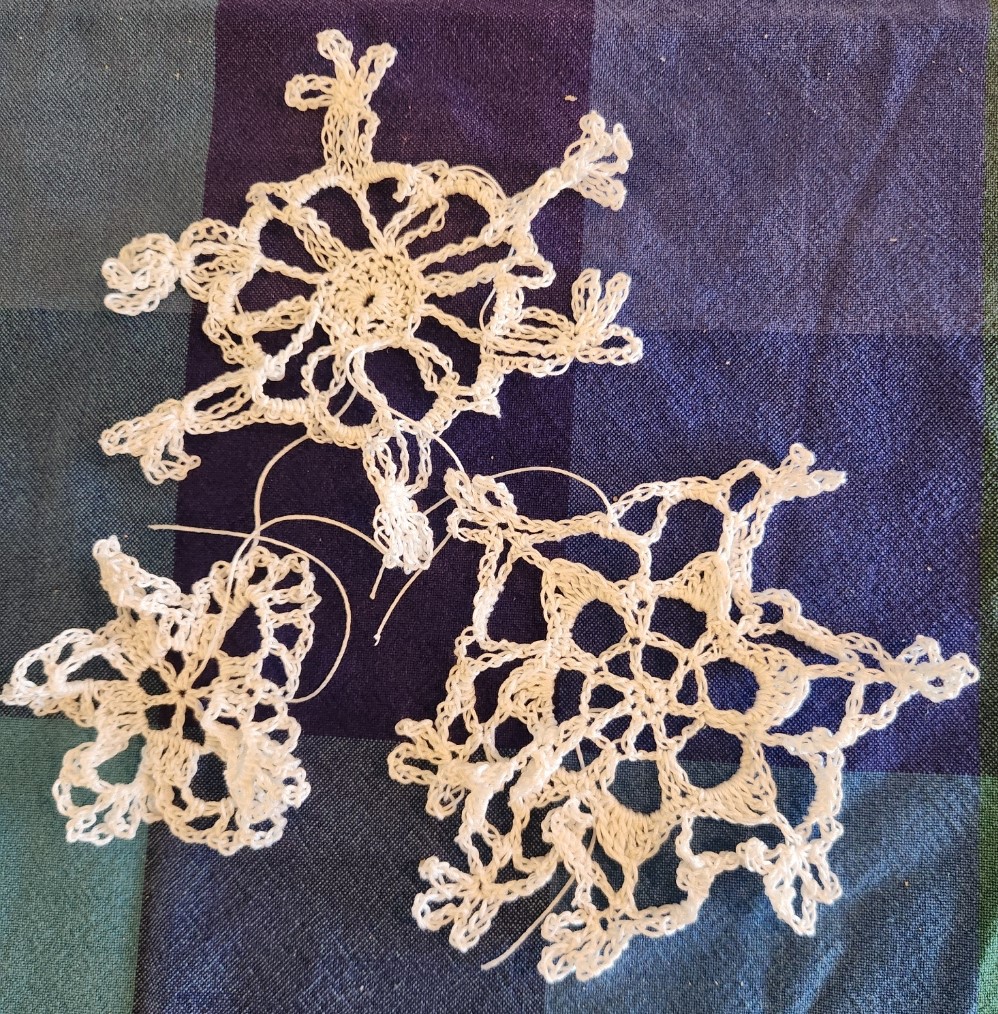

And I’ve been crocheting snowflakes. Not to keep cool but as a probably-the-case present for Elder Spawn, who has moved cross-country. It’s unlikely that we will be able to enjoy the family tree together this year come holiday time. A first for Casa Magnifica. So I have promised to make new snowflakes for what is now Casa Magnifica del Oeste, and ship them plus some of the family ornament stash, to furnish the new tree. I’ve got a half dozen complete. Six more to go, plus pin blocking and stiffening them for best display. Here are the first three, still looking sad and crumpled, right off the hook.

All of these are from this book. I have another one with better patterns. Someplace…

What’s next? Another stitched doodle on a thrifted linen rectangle, possibly to use up some of that black Sulky on a higher count ground. But more on that later this week.

ELIZABETH HARDWICK ON BIAS?

Once again a chance image on Facebook throws me into a frenzy of charting. The Friends of Sheffield Manor group posted this image of Elizabeth Hardwick, Countess of Shrewsberry. attributed to the school of Hans Elworth. It’s accession 1129165 of the UK’s National Trust collection.

Obviously what struck me were the sleeves. I tried and tried to chart them on the diagonal, but the geometry worked out much more cleanly if done straight. Now sewing, especially historically accurate construction is not my strength. But I ask folk more versed in it than I am, was it possible that if embroidered linen was used for those sleeves might they have been cut on the bias and not with the grain? The motifs look grain-wise at the collar, but are clearly sitting “on point” on the diagonal for the sleeves.

In any case, I’ve added the graph to the on-site free collection here. My rendition of it is approximate, but as close as I was able to achieve. I’m fuzzy on the exact shape of the free floating rondels occupying the empty areas where the chain rosettes meet. And their color is also problematic. Some are brown, some red, and some a pale indeterminant color – it might just be fading of the paint.

I lay no claim to the design itself – only my graphed rendition. Like most of the pieces offered here on String, this is available for your personal use. It’s Good Deed Ware – if you work it up please consider paying the kindness forward, assisting someone in need, calling a friend or family member who could use a bit of cheering up, or otherwise making the world a tiny bit more pleasant. And please note that my representation of this design is copyrighted. if you are interested in using it commercially or for larger distribution, either incorporating it into a pattern for sale or other dissemination, or if you want to use it on items that are made for sale or donation, please contact me.

And as always, I love to see what mischief the pattern children are up to out there in the wide-wide world. Feel free to send me a photo or a link. And if you give permission, I’ll add your work with or without your name (as you desire) to the growing Gallery page here on String.

VALENTINE’S DAY 2024

Among my other projects, I’m working away on sequels to my two book series. Those who know me know better than to ask when they will be released, but progress is being steadily made on The Third Carolingian Modelbook, and on Ensamplario Atlantio Volume III.

EnsAtl3 is moving along faster, in part because it’s largely my own doodles with no time spent researching, documenting, writing prose descriptions with counts, or creating indices. As I was playing in it today I felt a jolt of magnanimity, and in light of the season, I decided to share a small preview. As ever, an easy print/easy read PDF can be downloaded from the link below, or from my Embroidery Patterns page.

This is my own original design. I haven’t stitched it yet. When I do I will come back and add a photo. The band repeat is 47 units tall, and 18 units wide. Two cautions:

- In an uncharacteristic move for me, the points of the arrows are formed by two half-stitches. I try to avoid these, but to get a sharp arrow, they were essential.

- The arrows themselves are NOT aligned on the center line of the hearts. Were I to do so, there would be a lot more half stitches. Be aware of this and don’t be alarmed when the shaft is one unit to the right of the heart centers. I did this uniformly throughout the design – every arrow regardless of up/down orientation is shifted to the right of the heart centerlines.

I can see this stitched for love onto the collar and cuffs of a paramour’s shirt or chemise, or adorning the linen of a beloved offspring. Archers especially might be charmed by it. Of course it can also be used on a band sampler – especially one celebrating a wedding.

To download the Hearts and Arrows Border in PDF format, click here.

Like all the other downloadables on String-or-Nothing, I offer this as good-deed-ware. If you use this, please pay it forward by assisting someone else, or making the day a bit brighter for a friend, family member, acquaintance, or stranger. And also as usual, if you want to use any of these patterns for commercial purposes, either for combination into a new published design work, or to produce for sale or donation (especially in quantity) please contact me before doing so. But please feel free to use it as you wish for your own private enjoyment. And if you want to share a photo of your piece back to me, either for inclusion in the Gallery, or just for me to see – such things always make me smile.

CHATELAINE RIBBON FINISH

A super-quick project for sure. Younger Spawn gave me a chatelaine with a little metal purse for the holiday. I quickly attached my existing tools, put a piece of beeswax in the purse, and set out to use it. But I found that the thing was a bit heavy, likely to injure standard t-shirts and blouses, and pinning it to the waistband of my jeans wasn’t a feasible solution. But it’s a tremendously handy thing.

Stash to the rescue!

I had a length of evenweave linen ribbon I bought at the old Sajou store during our April in Paris trip a few years ago. I’ve been saving it for the right application. This was it.

I cut a length, charted out a new design specific to its width, and set out to stitch it more or less double-sided (not entirely so, but close enough) to use as an award-style neck ribbon to which the chatelaine could be securely and safely pinned. I started stitching on it on 5 January. And in less than two weeks, I have my first 2024 finish.

This is it, upside down so that the signature in the center back reads in the correct orientation. Note that I’ve left the overlap area free from stitching. It’s actually four layers of the ribbon linen thick – the ends folded over each other and securely stitched down. On top of that I also reinforced the back to prevent it from snagging on shirt buttons, and to give the chatelaine pin even more to grab onto.

Yes, that’s the same bit of nylon jersey fabric I used last week for mending. (Waste not, want not.)

Here’s the whole thing with the very appropriate rose pin in place, neatly figleafing the bald point center front:

The extra fluffy pullover doesn’t make an attractive backdrop, but I plead the current cold snap. I’m comfy. And now armed for my next stitching battle!

UPDATE:

The doodle page for the pattern I used on the chatelaine is now available on the Patterns tab here at String. Click below and scroll down to the bottom of the page.

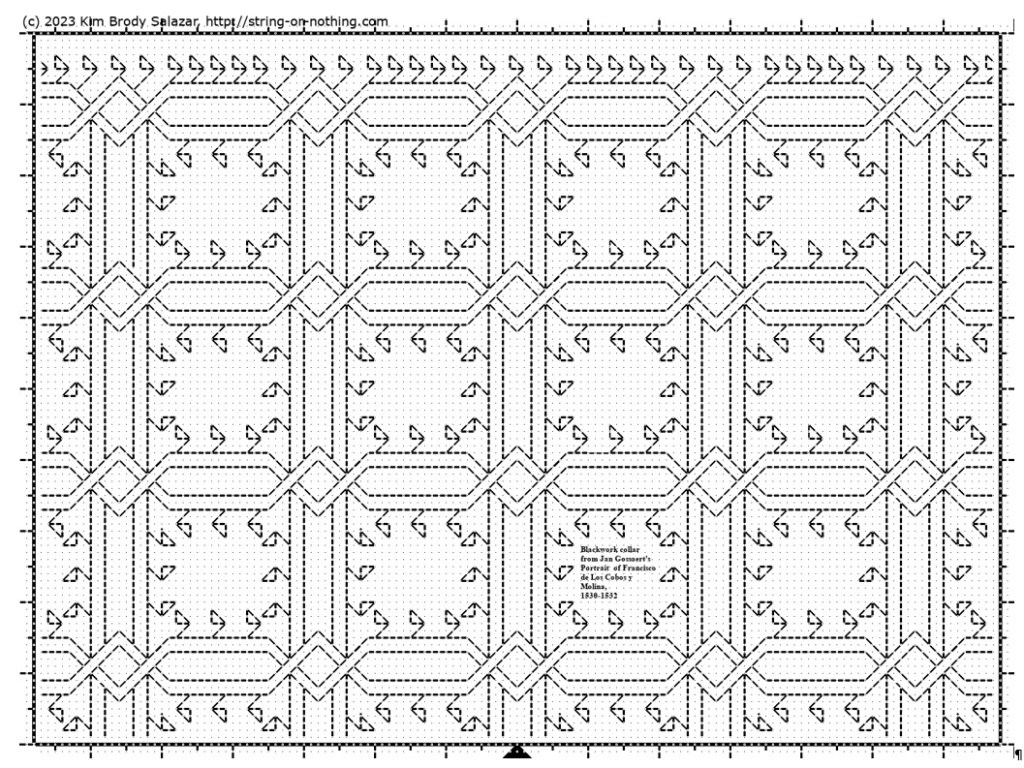

A SPANISH GENTLEMAN AND HIS COLLAR

Once again discussions on Facebook have brought a portrait to my attention. Elspeth over at Elizabethan Costume has found something I’ve been seeking for a long time. An portrait of an individual with a Spanish name, with a sitter that is wearing what we would describe as blackwork.

While 19th and 20th century discussions of blackwork in the Tudor period often call it Spanish Blackwork, and offer “Spanish Stitch” as another name for double running. But there are very few portraits of Iberian individuals wearing it, as one might think there would be if the folk attribution of Catherine of Aragon’s introduction of a style already popular in her homeland was to be corroborated. This portrait, dated 1530-1532 is by Jan Gossaert, and is part of the J. Paul Getty Museum’s collection, accession 88.PB.43. It depicts Francisco de los Cobos y Molina, who served in Charles V’s Holy Roman Empire court as a trusted secretary and advisor. The Morgan Library and Museum notes the absolute identification of the sitter. Note that shortly after this was painted, Catherine far away in her English court was only a year away from Henry’s declaration that their marriage was invalid (1533) and her subsequent sequestration.

There are higher resolution pictures at the museum link, above.

To say thank you to Elspeth and to spread my joy in finding a heretofore unknown bit of delight, I share a graph for that collar.

Click here for a full size downloadable PDF of the pattern below.

Now. How “authentic” is my representation?

I’d say it’s no more than an honest representation. Remember that the original I am working from is a painting. The painter did his best to capture the alignment of the verticals with the horizontal interfaces, but he fudged almost all of them. What I’ve done is to show the design elements in as close to the original proportions as I could manage, with the correct number of “pips” inside the boxes formed by the repeat, and represent as well as I could the marching row of them more or less evenly spaced across the top edge of the collar band. Like the painter, I have fudged the geometry of the thing to make it fit. And of course the nature of those pips is open to interpretation. Little hoof-like triangles? A three pronged fork, bent to one side? Should the ones in the square be closer to each other than I show? Should the middle one of each box side be taller? All of these would be as valid as what I show. After all, a tiny blob of paint can be seen in many ways.

I will be adding this pattern to the Embroidery Patterns page here at String, so it can be easily found in the future. If you choose to try out this design, please feel free to share a photo. I do so enjoy seeing what mischief these doodles attempt out there in the wide, wide world.

MORE ON THE UNSTITCHED COIF EXHIBIT

It’s coming! Here is the official flyer.

The stitching on the flyer is by Toni Buckby, the Unstitched Coif Project’s Fearless Leader. The original she reproduced under the auspices of the V&A is in their collection, It’s rather well known, made between 1570 and 1599 (Accession T.12-1948), but is rapidly deteriorating because the dye used on the black silk continues to eat away at the fiber. The thing is extremely fragile these days, with the stitching crumbling, leaving only needle holes behind. As a result, the museum commissioned a stitch-perfect duplicate for educational outreach, to limit handling of the now endangered original artifact. Toni undertook this assignment, performing forensic analysis of the damaged bits, and examining old photos to puzzle out missing patterns, then sourcing materials and employing methods as close as possible to those used in the 1500s. Toni says that the reproduction informed the Unstitched Coif project concept and planning. The linen sourced for that is the same 72×74 count recommended for Coif participants.

In addition to the gallery exhibit Toni plans to update the Coif project’s official website with photos of all 130 submitted pieces. Each one is a different interpretation of the same drawn outline. Some are monochrome, some are multicolor; some include counted fillings, others use freehand fillings; some are surface embroidery of other styles; a few sport beads, paint, or other inclusions. The website has already been updated with a suite of downloads of the drawn outlines, prepared for several paper sizes. Toni is also exploring the possibility of a printed book, with photos and accompanying blurbs for each coif, as supplied by its stitcher. I do not know if the book will be a limited circulation run or if additional copies will be available for non-participants to buy.

I am looking forward to seeing the exhibit in person. I will be flying to the UK from Boston, to be at the opening event and at a private reception for participants later in the week. I will be taking a lot of photos of the coifs plus other exhibits in situ. If you are among the overseas participants who won’t be able to attend, and you want to see how your piece is displayed, please message me. If I know what to look for (a photo would help), I will try to find your coif and take a picture of it as it hangs in context with its neighbors.

BUZZ ON BEESWAX

I keep seeing questions about waxing threads on various social media needlework discussion groups. I usually end up retyping this. So to make reference easier while offering up this Helpful Hint, I take the time to write it out in long form.

I use beeswax on my threads for blackwork and cross stitch. I only use 100% beeswax, not candles or other beeswax products that often contain fragrances, colors, or agents to soften (or harden) the wax. Whenever possible I buy it direct from beekeepers, at farmers’ markets or county agricultural fairs, avoiding the overpriced boxed or containerized offerings at big box craft and sewing stores. I’ve also bought it via Etsy and Amazon, but am leery of super-low priced imports that might contain adulterations. I look for domestic producers with a range of local bee-related products instead, especially those who guarantee the purity of their product. Even then it’s not a very expensive purchase. A one-ounce mini log is currently running between $1.50 to $2.00, and will last for years and years. By contrast those Dritz plastic containers of wax with no ingredient labeling are about $5.00 for an unweighed bit I estimate to be less than 25% of the mass of the one-ounce mini logs.

What does beeswax do for me?

- It tames surface fuzz on my threads, making them sleeker and smoother.

- It aids in needle threading, making that much easier and quicker.

- It cuts down on differential feed when using two plies of thread together. That means that both plies are used at the same rate, and I am less likely to end up with one extremely shorter than the other after a length of stitching.

- It eases thread passage through the fabric and “encourages” threads to lie next to each other in mutual holes rather than earlier threads being pierced by successor stitches. I find this leads to neater junctions in double running stitch and neater stitch differentiation in cross stitch.

- Since I stitch with one hand above and one hand below, occasionally the working thread is “nipped” as it is passed back from the unseen back to the front. A problem that leads to work-stopping knots and snarls that have to be teased out. Waxing cuts way down on this because the thread fibers are kept closer and are more difficult to snag.

- Less drag from less fuzz and eased passage through the work allows me to use a longer length of thread than I can get away with without waxing. Even a little bit of extra length before the thread degrades enough to make the work messy makes it easier to achieve a uniform appearance when working the second pass of double running, or doing the “return leg” of a line of cross stitches.

I wax my threads for blackwork and cross stitch: cotton, silk, faux art silk (aka rayon), linen – everything except wool. Note that I tend to work on higher count grounds rarely venturing below ground thread counts of 32 per inch (16 stitches per inch when done over 2×2 threads), and usually in the 38-46 range, sometimes up to 72 threads per inch (18 to 23, and up to 36 stitches per inch respectively). My blackwork and cross stitches are relatively short, so thread sheen is not a factor. If I am working satin stitch, or a longer linear stitch that takes advantage of thread directionality and sheen, like satin stitch, I skip the wax.

I usually keep two of those single-ounce logs going – one for dark colors, the other for light because even the best threads will crock dye and leave traces of lint in the wax as I use it. Since I do a lot of blackwork with strong colors, I don’t want to run a white, yellow or other delicately tinted thread through the accumulated color left behind by the darker ones. Below is a one-ounce mini log, untouched; and the remains of an identical log after about seven years of very heavy, daily use. The frugal will note that there’s more than enough in one mini log to break it in half, and use one piece for dark colors and the other for light, but that’s not what I did here. That grungy little stub used to look exactly like its brother. It’s so filthy now I may break down and melt the stub, skim off the lint and recast it in a silicon baking mold.

Applying wax to working threads is quite simple. I hold the bar in my hand, with the thread to be waxed between my thumb and the bar, under gentle pressure. Then I use the other hand to pull the thread across the surface of the wax once or twice. I don’t want to wax heavily – there should NOT be flecks of wax on the thread, and it should not feel stiff as a wick. In fact, after I thread my needle I usually run it once or twice through a scrap of waste cloth before use to remove any that might be there, before using the lightly waxed thread on my project at hand.

Back to when to use and when not to use beeswax. Here are a couple of examples. First, my project-in-waiting – the Italian green leafy piece. Lots of satin stitch. The dark green outlines are two plies of Au ver a Soie’s Soie D’Alger multistrand silk floss on 40 count linen (over 2×2 threads). Wax on all the outlines, even though they are silk. That infilled satin stitch worked after the outlines are laid out? More of the incredibly inexpensive Cifonda “Art Silk” rayon I found in India. No wax on the satin stitch. That lives or dies by thread sheen and directionality. While the stuff is very unruly and I do wax it when I have used it for double running or to couch down gold and spangles on my recent coif project, here doing so would not give me this smooth and shiny result.

And an example from the coif mentioned above. It’s on a considerably finer ground – 72×74 tpi. All of the fills are done in one strand of Au Ver a Soie’s Soie Surfine in double running. All waxed. The black outlines on the flowers and leaves are two plies of the latest batch of four-ply hand-dyed black silk from Golden Schelle, done in reverse chain stitch. Also waxed. The yellow thread affixing the sequins and used to couch the gold, the same Cifonda rayon “silk” used in the leafy piece, waxed, too. The black threads whipping the couched gold are two plies of Soie Surfine, waxed. But the heavy reeled silk thread ysed for the outline is Tied to History’s Allori Bella Silk. It’s divisible, and I probably didn’t do it as the maker intended, but that’s two two-ply strands, plus a single ply teased from a two-ply strand – 3 in all – worked in heavy reverse chain. That’s a longer stitch, thicker than even the black flower outlines, and because the stitch was long and I wanted to make it stand out from the other black bits, shine was part of what I needed. NOT waxed.

Many people have asked me if waxing makes the piece collect dust faster, leads to color migration, or makes the stitching feel heavy and well…. waxy, or if it stains the cloth when the piece is ironed. My answer is that I find no difference in dust accumulation on my finished pieces on display. And I see no color change, either. Beeswax has been used for stitching for hundreds of years with no ill effect that I have seen reported. Modern substitute thread conditioning products of unknown composition have not undergone that test of time.

As for a heavy, waxy feel – again, no. Not if you apply it lightly. I do cover my stitching with a piece of protective muslin when I iron it, and never iron pieces on which I’ve used the Art Silk anyway. I have never noticed waxy lines of residue on my ironing cloth when I have ironed my cotton, linen, or silk pieces.

So there it is. Waxing, why and how I do it. Your mileage may vary, of course.

THINKING, BUT KEEPING BUSY

A couple of people have asked if I’m taking a break from needlework in the aftermath of the great coif project.

Nope. To be truthful, I am filling my time with far less challenging pieces while I contemplate the next big project.

First, I’ve returned to the third forehead cloth. I’ve done two before and love wearing them instead of bandannas to contain my hair on windy days. I do a little bit on them in the afternoons, and in the evening catch up on my sock knitting.

The socks are my standard issue toe-ups on anything from 76 to 88 stitches around, depending on needle size; figure-8 toe (an technique unjustly despised by many), plain stockinette foot, German short row heel, then something interesting for the ankle. Mostly improvised. The only hard part is remembering what I did on that ankle so I can repeat it on the second sock.

The forehead cloth is fairly flying. It’s all one pattern, on cotton/linen yard goods that works out to about 32 threads per inch. That’s as big as logs compared to the coif’s linen. I’m trying out Sulky 30 thread (two strands). It’s ok, but I am not so fond of it I’d throw over softer, more fluid flosses. I am betting though that it will stand up to hard laundering better than standard cotton floss. The stitching on my other two forehead cloths, done in silk, has survived quite nicely. Unfortunately the ties – folded strips of the same ground – have totally shredded and been replaced twice on each. I may move to narrow store-bought twill tape for the ties, instead. Jury on that is still out. Oh, and yes, there are mistakes on this. Some I’ll fix, and some I won’t. Have fun hunting for them. 🙂

While I’m here, I’ll share a tiny blackwork hint.

I’m doing double running but this will be relevant to those who favor back stitch, too. See those “legs” sticking out in the photo above? As I passed those junction points I knew I would be coming back again, from a different direction. It is far more difficult to hit the exact right spot when joining a new stitch to an existing stitched line (both perpendicular as here, and diagonally) than it is to mate up to a stitch end. Those legs are there so when I come by again I have a clear and simple target for the point of attachment. This saves a lot of time, minimizes my errors and helps keep my junctions as neat as possible. Try it, I think you’ll find the trick useful.

What am I contemplating for my next project? Possibly a blackwork/sashiko hybrid. I have a barrel chair, a wreck salvaged from the trash, that I had recovered in Haitian Cotton back in the early 1980s. It has survived four house moves and two children, but although the back and sides are in good shape, the seat cover and the area just under the seat are both shot. I still adore the thing even though it doesn’t really fit in with the rest of the house’s style. So it’s going up into my office. I plan on recovering the shredded areas with patchwork denim overworked in white running stitch. The denim will be reclaimed from various outgrown and destroyed garments I’ve held onto against just such a future need. Since I do not plan on replacing the rest of the upholstery, I’m counting on those flashes of white to bring the seat and the rest of the piece together.

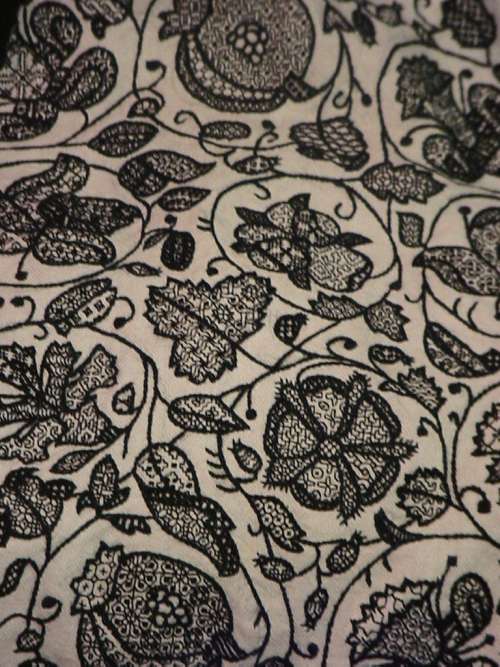

ANOTHER PORTRAIT, ANOTHER REDACTION

About a year ago a member of the Italian Renaissance era fashion discussion group, Loggia Veccio on Facebook asked for help decoding the blackwork on the sleeves of this portrait. I volunteered, but heard nothing back. Today she came forward again to repeat her request. So I oblige.

The first thing I did was try to find the full attribution for the portrait, plus a better, higher resolution image than this repasted one.

The original is held by the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, Accession K1651. While it’s not available on the museum’s own website, it does have a page in the Art UK on line collection. The accompanying information cites its date as circa 1500, and the working title as “Portrait of an Unknown Young Woman.” The blurb goes on to say that it has some congruence with works produced by Carpaccio, but stops short of definitively identifying the painting as his.

On to that sleeve. It’s a relatively simple pattern, but redacting from paintings is never as easy as doing so from an actual textile. In this case while the design looks quite regular at gazing distance, up close examination shows that multiple interpretations of the repeat are represented. I’ve attempted to reduce those to a most probable approximation, but it is just an approximation.

As usual, my assumptions were square units, all of the same size, mirrored both horizontally and vertically. I further assumed no diagonals based on the stepwise total appearance. And while I first thought this might have been done in one continuous line, examination of multiple repeats showed that it was most probably done as lozenges rather than a united whole, with small “islands” filling in between the main bird-bearing motif. Here is my best guess.

As usual, a printable page with the pattern and accompanying text is available by clicking here, or popping over to my Embroidery Patterns tab.

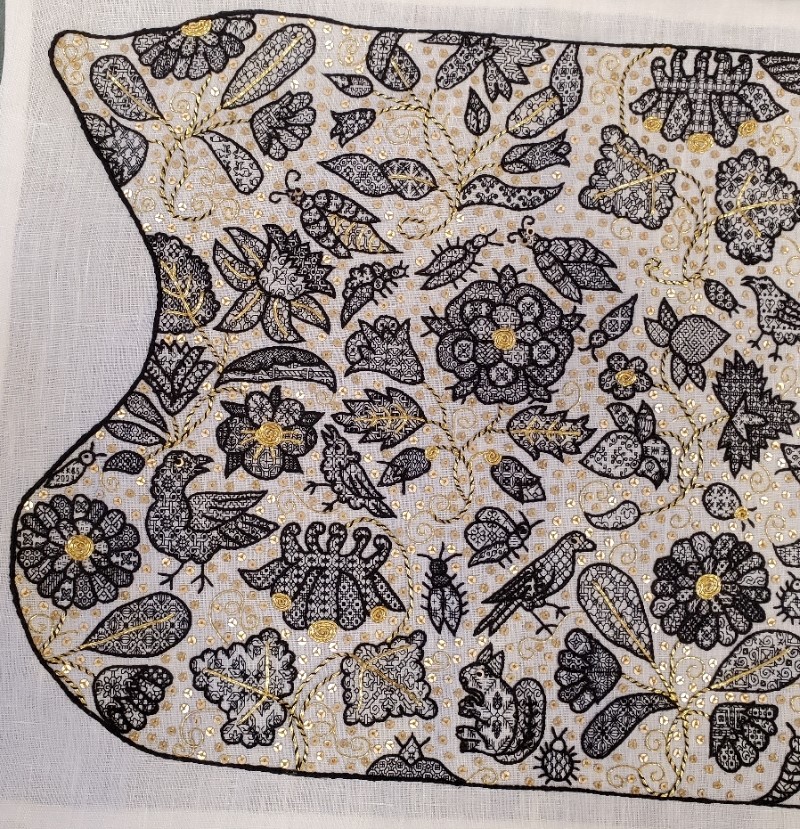

UNSTITCHED COIF – FINISH. THE FILLS

As promised here’s the breakdown of the design, motif by motif – a guided tour of what I was thinking or not thinking about. This is turning out to be way longer than I expected. Feel free to scroll down to the eye candy and ignore the prose.

First, on the general aesthetics, I already confessed yesterday that this piece is a departure from the strictly historical, using stitches, materials, and fills that have no specific point source in a particular artifact contemporary (or near contemporary) with the original Victoria and Albert Museum piece of ink-drawn linen. But in spite of that I’ve tried to stick to general aesthetic. It was a time of “more is more.” Pieces like this coif were status items that proclaimed the wearer’s wealth. I heard Thistle Thread’s Tricia Wilson Nguyen lecture at Winterthur about how copious precious metal spangles, threads, and even lace served as walking bank accounts, shouting prosperity but still being available as liquid capital to an owner whose fortunes dipped so low that reaching for a scissors to snip off a bit for ready cash was a welcome option. To that end, I’ve doubled down on the gold accents. But not being as flush as landed gentry from the late 1500s, I’ve used imitation gold thread and gold tone mylar rounds.

I’ve also tried to emulate the more lush aspects of some historical blackwork pieces, that created depth and shaded nuance by using fills of different visual density, augmenting the effect with raised outlines. I would have liked to use a plaited stitch for the stems, but it’s clear that the original artisan didn’t leave room for them, so I settled on outlines that were markedly heavier than the fills, topped off by a whole-piece outline that was even thicker and more dimensional.

I also like the difference in blacks used. The fills in the thin modern-dyed spun silk single strand are dark enough to look lacy and contrast well with the ground. The outlines, done in the boutique, small batch historically dyed double strand (also spun) are a much softer black. In some places the black takes on a reddish or brownish tinge, or moderates to an even less dense charcoal. If they were as deeply toned as the fills I think that each leaf, petal, or wing would present more as a grey-scale visual mass rather than letting the fills speak louder than the outlines. Finally the deeply black modern dyed but glossier reeled filament silk used in the perimeter then echoes the black of the fills, and makes a world of difference to the piece, pulling it all together. All black, all different, and all contrasting with each other.

On planning and fill selection, I winged it. I didn’t sit down and plan anything. I picked fills on the fly, with only a vague idea of where I would put dense, sparse, and intermediate fills as I began each sprig or group. Some succeeded quite nicely, others I would re-do differently had I the chance. Would I ever sit down and plan an entire project’s density/darkness/shading map ahead of time to avoid this? Probably not. It’s more fun to bungee-jump stitch.

On to the piece. First a quick recap of the whole item:

On this whole coif shot I can see three center circles of motion in the design, one surrounding each rose, and one surrounding the two centermost unique motifs – the borage flower/strawberry pair. The rest of the flowers are surrounding those elements. Maybe I see them because I’ve been staring at the thing for so long, or maybe my admittedly ornate but heavily outlined rendition with the gold whipped stems sinking into the background pulls those surrounds forward. When the exhibit comes around and I can see all the other pieces it will be interesting to see what other symmetries they accentuate.

We’ll start at the upper left. Although I began at the lower right, it’s easier to walk across starting at this point. I give fill counts and cite the number of fills I used from the project’s official website. Now some of the ones in my doodle notebooks duplicate or near duplicate those (we were after all mining very similar sources), so I apologize if any double-listed ones ended up in the wrong pile.

The first motif in the upper left I have been told is a marigold, one of six on the piece. It’s truncated at the edge by the indent. The marigolds were especially hard to work because those little jelly bean spaces of their petals were so tiny that most of the fills I had included repeats too large to be useful for them. I tended to use four repeats in the outer petal ring, repeating the sequence four times. The inner ring used different fills, usually two. Fourteen fills in this motif, twelve are mine, including the bunny rabbits. The other two are from the collections redacted by Toni Buckby, our Fearless Leader, and are available at the Unstitched Coif project website.

Immediately to right of the partial marigold in the corner is a truncated carnation or gillyflower (hard to tell them apart). Three of these are here, but only one isn’t cut by the perimeter. At this point, relatively late in my stitching I went out on the hunt for additional fills, and redacted a couple of pages of them for the upcoming third Ensamplario Atlantio volume. One of particular note is the leaf at the lower right, with that flying chevron shape, one of several I drafted up from a photo of a blackwork sampler, “Detached Geometric Patterns and Italianate Border Designs with Alphabet” 1697. National Trust Collections, Montacute House, Somerset, NT 597706. The twist and box of the sepal is from the same source. Yes, I know they are later than the coif’s original. Since by definition anything I doodle is even later still, I didn’t see the harm it using them. 18 fills total in this sprig, six from Toni’s redactions, two from mine, and ten of my own doodles.

Next to the right on this photo cut is a columbine. It’s barely snipped, and one of three on the piece. The large leaves made good showcases for some of the bigger repeats, even with the gold overstitching. As a result on this sprig we’ve got only five fills, two of which are from Toni’s pages. On this motif as on all of them, I tried to use fills of contrasting effect. Here in the flower we have the very strong linear grid of the main pattern, paired with the angular acorn spot motif. This flower is also an example of introducing movement or syncopation by NOT using the same grid for adjacent motifs.

Back to the left edge now. This sprig includes a narcissus or daffodil, plus a viola and something indeterminant, possibly a blossoming narcissus, all on one stem. Leaves are also of multiple forms. There are only two of this hybrid sprig on the piece, both nipped by their respective edges. All those little areas add up to 19 fills on this one. I’m particularly happy with the density effects I got on this one, with the narcissus throat, the leaf curl, and the viola sepals bringing darker depth. I did try to find two patterns of similar density for the lower petals on the narcissus, too. I have to look closely to remind myself that they are two petals of one design and three of another.

Next over is the rose. I’ll come back to the bugs that surround it. There are two roses on the coif, and two tiny partial bits on the lower edge. In truth, I’m not enthused about the way the big flower turned out. I like the sepals and the outer ring of petals (three fills, all of the same tone), but the inner rings aren’t well differentiated – although I used one fill for all five of the middle ring and that isn’t bad, that inner ring with its three fills is rather boring. Were I to do it over again I’d make some different choices here. I used sixteen fills in all for this sprig, including two of Toni’s set.

The creatures dancing “ring around the rosie” includes seven bugs and two birds. Visually they do make a circle around the rose, with one larger bug flying off above the narcissus. Here I spy a mistake, and the thing being in transit right now, it’s too late to fix. I meant to go back and add little gold stripes to the body of the bug to the upper right of the rose. Those tiny bits of couching were the ones I liked least to do. So it goes.

Like the marigold petals, the body parts of all the coif’s bugs were a challenge. Some are so tiny that it’s hard to squeeze anything resembling a pattern into them. I doodled on those, but I tried hard to make the doodles unique. In a couple of cases I found I had made a duplicate of a pattern stitched before, and went back to make modifications to one of the inadvertent pair. All of the large bugs with sequin eyes have a feature in common. Although it’s hard to see because of the stripes, I used the same pattern for both of their wings, but rotated it 90-degrees to give them extra movement. I have found no historical precedent for using directional fillings this way. Taken as a group, there are 27 fills among all of these bugs and birds, four of which are from Toni’s pages.

Reading across, the strawberries are next. (I’ll cover the bird to its right in the next post). There is only one strawberry sprig on the project, and it’s another challenge because of the small petal and sepal spaces. This is another motif I count as only a partial success. I like the top strawberry, flower, and leaf, but I think I should have chosen differently for the lower strawberry. Possibly working the sepals for the second one and that leafy whatever that terminates the sprig both darker. That would have made the lighter fill in the bottom bud a bit more congruent. Thirteen fills in all, four of them from Toni.

Back to the left hand edge of the photo, below the narcissus/viola stem are the large bird, and the second marigold (cut off at the edge). There’s also a tiny bug above the marigold in which I worked “KBS 2023” as my signature. This flower was my finishing point – the last one stitched. Most of the fills in the petals were improvised on the spot. The bird carries an interlace and star I remember doing on my first large piece of blackwork, an underskirt forepart, back in 1976. That piece however was worked on a ground that was about 28 count (14 stitches per inch), not 72 count (36 stitches per inch). You may even recognize some of the other fills I reused on the coif in the snippet below. Vital stats on Marigold #2 – 12 fills for the whole sprig including the large bird, one of which is Toni’s.

The second columbine, to the right of the bird, grows from the bottom edge of the coif. I wonder how many people will look closely enough at the leaf on the left to realize that it’s bugs. I was thinking bees, but I’ve been told they read more like flies, and “ick.” There are four fills in this sprig, one of which is Toni’s.

Adjacent to the right we find Needles the Squirrel, his friend the round bug, and one of those rose snippets. I group them together for convenience. Needles’ pine spray fill is mine, and came about during discussions on line and in the Unstitched Coif group’s Zoom meet-ups. Someone mentioned using an acorn fill for their squirrel, but UK folk were quick to point out that the indigenous Red Squirrel, who preferentially dines on pine nuts, was deeply endangered by the invasive Grey Squirrel, who prefers acorns. So I doodled up the spray, shared it with the group, and used it on mine, bestowing the appropriate name. I’ll find out in December if anyone else used this fill. I also did the directional shift in Needles’ ears. There are only six fills in this group.

Marigold #3 is in the right corner of this photo. He’s also rather a mess. I should have picked two dark and two light fills for the outer ring of petals, instead of one dark one and three intermediates. I did rotate the direction of the fills around the circumference. Oh, the snails? A variant of those snails with their wrong-way curled shell is on the majority of my blackwork pieces. Not quite a signature, but not far from one, either. There are 17 fills in this sprig, one from Toni.

On to the center of the piece.

Back up to the top of the center strip. Here we have the sadly bisected bird, with the fourth marigold to its right. Although the petals are a bit uneven, I did try something specific with this one, using two fills in of similar density in the center ring, and four also similarly sparse fills in the outer ring. I count this one as a success. Together these two motifs contain 13 fills, two of which come from Toni’s pages.

Below the marigold is the singular borage flower. There’s only the one, and he’s at the center of it all. I will cover the caterpillar later. He’s one of my favorites in the piece. I especially want to call out the tiny paisley at the bottom of the stem. The fill there is one that Toni redacted from a coif, V&A Accession T. 12.1948. It is very unusual fill, with the exception of a few that use a circle of stitches radiating from a center hole sunburst style, it is the ONLY historical fill I have seen that uses the “knight’s move” stitch – two units by one unit, to produce a 30-degree angle. Knight’s move stitches are very common in modern blackwork, but exceedingly rare in historical pieces. Knowing this I’ve drafted up hundreds of fills and in keeping with this paucity, have only included them on three or four of the most egregiously modern. The little stirrups in that paisley open up a whole new world of possibilities. Borage contains 11 fills. Five of them including the stirrups are Toni’s.

At the bottom below the borage is Carnation #2, attended by four insects. I am also fond of this one, especially the long skinny bud on the lower left. That striped lozenge filling is one of Toni’s and I adore it. With all the folded leaves there was ample space to play with density, and it was fun to pick these fills on the fly. All the more so because the combos worked. The insects, from lower left, a caterpillar or worm, an amply legged spider, a moth, and a beetle, are a playful way of rounding out the space between the center and the side areas, the latter being (mostly) mirrored near-repeats. This group holds a whopping 23 fills, nine of them from Toni’s redaction page.

And back up to the top we go. Carnation #3, another truncated motif. Like the last carnation this one had a lot of play for contrast. It was actually among the earlier sprigs I stitched because I began upside down in what is now the upper right hand corner. This is the motif on which I began to get a better feel for the size of the repeats in the fills and how that size related to the dimensions of the shape to be filled. There are 19 fills in this one, including two of Toni’s.

Below this last carnation is Rose #2 and its bug and bird armada. Don’t worry, I am not double counting the moth I included with Carnation #2. I like this rose slightly better than the other one, but don’t count either one as a stunning success. I may excerpt the rose and try again. In any case you can see that I’ve hit full stride here in using fills of various repeat sizes.

For the most part I stitch fills then go back and outline them when the motif is complete. I have always found that to be a forgiving way of working that allows fig-leafing of the fills’ often all to ragged edges. But on the caterpillar (my favorite insect on the coif) I started at the head, stitched its fill, and then outlined it. I continued in this manner segment by segment. I did this because I knew if I waited until the end, my divisions between the body segments would get muddy. I wanted to make sure that the little center divots that ran down his back were seen. I probably wouldn’t have attempted this if I hadn’t seen others in the Unstitched Coif group Zoom meetings working up all of their outlines, then going back and adding fills.

Rose #2 and accompanying critters used 31 fills, including six from Toni’s pages.

Below and a bit to the right of the rose is Columbine #3, and a partial rose. There’s also a lump from which the columbine sprouts, but that may be a mistaken interpretation on my part. Perhaps that was supposed to be an arched stem. Maybe yes, and maybe no. I spent a lot of time dithering about how to handle the columbines. Those curly narrow top protrusions in particular limited the size of the repeats that could fill them effectively, especially if I wanted to play up the contrast between the gold topped and plain petals. The circle fill (one of Toni’s) worked nicely and set the tone for my later choices. In this grouping there are nine fills, including Toni’s circles.

Back up to the top for Marigold #5, which happens to be the first bit I stitched. The leaf with the larger butterflies was the first fill I did. When I started I thought that stitching over 2×2 threads might be problematic, so I worked this one over 3×3. However my eye and hand are SO attuned to 2×2 that it was clear that the new count would drive me to distraction, so I quickly switched to my standard. But I didn’t pick out the errant leaf. I doubt if I hadn’t mentioned it you would have noticed. In any case you can see that I was very tentative on fill repeat size on this first flower. For example, I could have used much larger repeats in the leaves. Still this was the try-out. I beta tested using fills aligned in radial directions, the gold center coil (here only a half), veining and stems in couched gold double strand, and curls in couched single strand. And adding spangles. Once they were in I noted how the stems disappeared, so I went back and whipped them with black to make them stand out a bit from the background. This sprig uses 15 fills.

Below the marigold is the second Daffodil/Narcissus and Viola sprig. I’m generally pleased with it, although I wish I had saved the feather fill for one of the birds. You will note that I take no special care in always whipping the stems in the same direction. I did them in the most convenient/least awkward direction because needle manipulation to avoid catching previously laid down work was very important. As I went on I destroyed most of the sequin/French knot eyes and some of the smaller couched gold bits by snagging them with my needle tip or smashing them with ham-handed stitching. I ended the project by replacing all of the eyes. There are 19 fills in this motif, two of which are from Toni’s pages.

Last but not least we have yet another marigold, Marigold #6 with bird, bug, and bits. I confess that the marigold was my least favorite to work, even by the time I did this one – only the second one I stitched. That little intrusion below the bud may also be a vagrant bit of curl or stem, but I filled it in anyway. This bird has the first sequin/french knot eye I did. I also experimented with three sizes of little seed beads, but decided that they were too dimensional and/or just too big for this use (the paillettes I used are only 2mm across). Our final motif has 19 fills, including one from Toni’s page.

That ends the guided tour. The total count of unique fills on this piece is 274. 51 of them are from the pages of fills redacted by our Fearless Leader, Toni, and posted on the project’s home website. The remaining 223 are mine, mostly taken from my Ensamplario Atlantio series.

Would I ever attempt something like this again? In a heartbeat. BUT I will never do another piece of this size and stitch count to deadline. While it was intensely fun every minute of the roughly 900 hours I was stitching, I prefer to stretch those hours out over a longer time period. Intense thanks to Toni and my fellow Unstitched Coif participants, for the opportunity, the learning experience, the encouragement, and the camaraderie. I am looking forward to the December exhibit, and to meeting as many of you as possible, in person.

When the flyer for the exhibit is released I will post it here on String, on Facebook, Instagram, and Linked In. In the mean time, reserve the date – it will be on December 18 through the 24th, at the Bloc Gallery, Sheffield Museums, Sheffield, UK.