UP CLOSE AND PERSONAL!

Yesterday a friend and I went to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, in specific to see the “Strong Women in Renaissance Italy” exhibit. We also took in “Fashioned by Sargent”, and wandered at will and whim through other halls, especially those in the new wing. All in all, it was a splendid day out, full of fascinating things to see and discuss, in excellent company. This post focuses on the Strong Women exhibit. I enjoyed the Sargent exhibit, too, but I took fewer photos. If my friend has more than I do, I might do a follow on about it though.

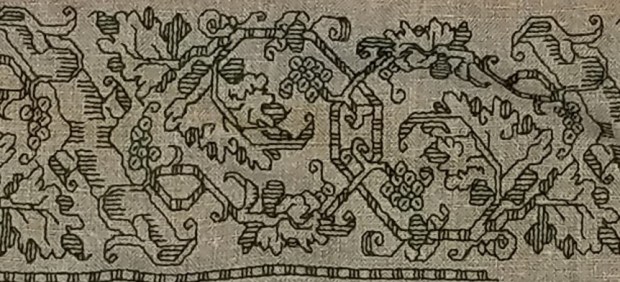

My main motivating reason to go was that the Renaissance exhibit included an artifact I’ve written about before. On loan from the Jewish Museum in New York is Honorata Foa’s red countwork Torah binder. Here is a photo I took at the MFA, of a bit that’s folded under in the official Jewish Museum photo linked above.

And an ultra-closeup. Note that the work is stitched over a grid of 3×3 threads.

Compare the original to my rendition, stitched on a big-as-logs, known thread count of 32 threads per inch, over 2×2 – 16 stitches per inch. Yes, I brought it with me, and photographed it held up to the glass display case.

Given the difference in scale of the two, and allowing for the inch or so of distance between them, a rough eyeball estimate is that the ground for the Foa original is about the equivalent of the 72-ish count linen we all used for the Unstitched Coif project. I also think that the weave on the Foa original is ever so slightly more compressed east-west than it is north-south. making the diagonals a tiny bit more upright than they are on my version. Fascinating stuff!

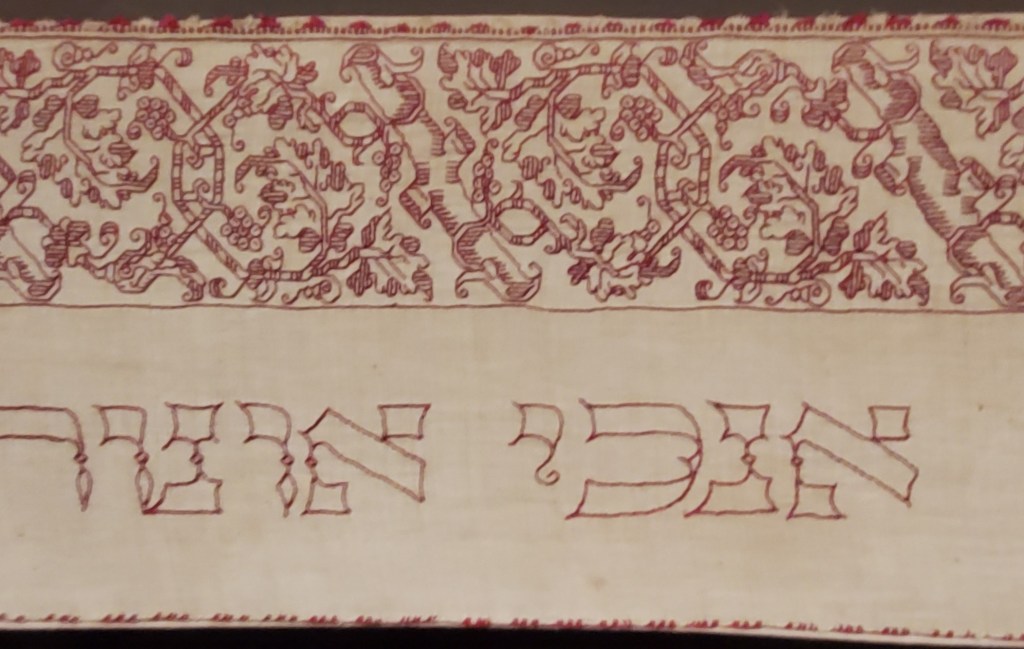

Now that I see the structure, scale and alignment of the Hebrew letters, I am beginning to think that they were written out and then over stitched, conforming as much as possible to the 3 over 3 rubric, as opposed to the regular countwork of the foliate strapwork above them. For one, they don’t inhabit the same baseline. And they do seem to employ improvised angles and variant stitch lengths, although they were clearly done by someone with a skilled hand who took pains to keep stitch length as uniform as possible over those variant angles. Even so, I may be able to improvise a full alphabet of them, adapting the missing letters from the forms of those that are displayed and known. Another to-do for my ever-growing list…

The Foa Torah Binder was not the only fascinating bit of needlework or textiles on display. On the non-stitched side, there were two long lengths of sumptuous silk velvet brocade, one with a manipulated texture (possibly stamped to create highlights and shadows). What struck me the most was the scale of the patterns. The pomegranate like flower units were as big as turkey platters – far larger even than the legendary motif on the front and center of the famous Eleanor of Toledo portrait:

The red one on the left was credited as “Length of Velvet”, from Florence, circa 1450-1500. MFA accession 31.140. The helping hand for scale was provided by my friend. The one of the right is “Length of Velvet”, possibly from Venice, 15th century. MFA accession 58.22. The photo at the museum link is closer to the color (the gallery was dark) and shows off the highlights and shadows impressed into the velvet. Those aren’t two colors, they are the product of some sort of manipulation of the nap. It’s not shorter in the lighter sections, it looks like it’s all the same length, but some just catches the light differently, which is what made me think that it might have been heat/water manipulated with carved blocks. But that’s just the idle speculation of someone who knows nothing about fabric manipulation techniques.

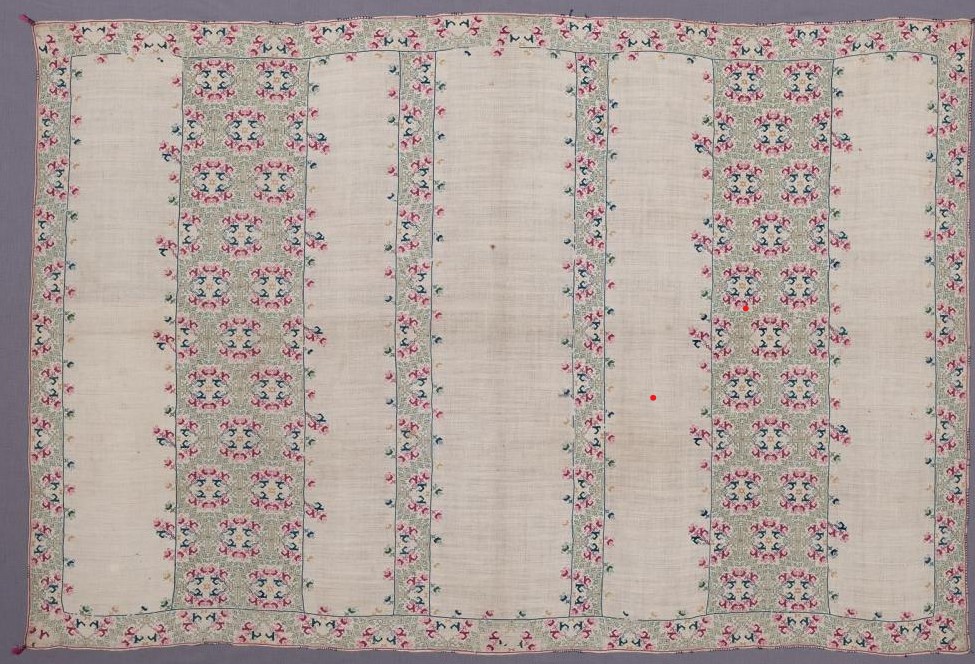

There was another counted piece. It can be difficult to judge the size of these from on line museum photo collections. Even when the dimensions are given, sometimes it just doesn’t input.

Photo above shamelessly borrowed from the museum page, where they describe it as a towel. The object’s name is a purported description of the stitches used. Punto Scritto and Punto a Spina Pesce MFA Accession 83.242, Italian, 16th century. Towel size? Nope. Tablecloth to seat 8 size. Wow.

Here are my photos.

Punto Scritto is another name for double running stitch. That’s ok. Punto a Spina Pesce has been used by the museum to describe some but not all Italian works featuring a variant long armed cross stitch. I think I can see that in the solid, heavier green and yellow lines.

Without having seen the backs, which would clarify this, I suspect that Punto a Spina Pesce (fishbone stitch), is the version of long armed cross stitch that is done by taking stitches with the needle parallel to the direction of stitching as one moves down the row, rather than the one where the needle is held vertically as one works. While the front of both is almost identical, the appearance of the reverse differs, with the horizontal-needle one being formed similar to the way stitches in herringbone are worked. The horizontal method leaves long parallel traces that align with the row-like appearance of the front. If multiple rows are worked this way, there are raised welts in all but the first and last row because the thread on the back is double layered as each consecutive row is added. In the latter there are also parallel lines on the back, but they are perpendicular to the direction of the stitching and overlapping threads on the back are also vertical. As to which one is “correct” – both seem to exist in the folk tradition, so pop some popcorn and sit back to watch the proponents of each fight it out.

A third technique is used. The colored buds are filled in using what I call “Meshy” – the drawn work stitch based on double sided boxed cross stitch that totally covers the ground, and is pulled tightly enough to look like a mesh net of squares. That’s most often employed as a ground stitch in voided work, but it is not uncommon in foreground use, as well. This one is on my charting list, too.

One last thought on this piece – it reminds me a bit of a strip I charted and stitched up a while back, as part of my big blackwork sampler. The source for that one is here, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accession 79.1.13, Strip, Italian, 16th century but the photo below is of my work.

There were more stitched pieces in the room, but the only other charted one was this adorable chubby unicorn piece in drawn thread. It’s tons of fun to stumble across things I’ve got in my research notes, but never seen in person. This one is MFA’s “Lace”, 16th century Italian, Accession 43.237. Long shot below borrowed from their site.

The museum chose to display this one scrolled, like they did the Torah Binder, so that only a portion was visible. Here are my three shots, left, right, and center.

Yes, there are many ways to achieve this look. But squinting closely one can see that no threads were picked from the work as in withdrawn thread work. There are neat little bundles of three threads where the solid areas meet the mesh ground. (Easier to see in the flesh than in my photo though).

It’s clear that this piece was cut from a larger cloth. I wouldn’t be surprised to find another fragment of it in another museum collection someday. That’s not uncommon. But for now, chubby unicorns, their big quaternary star and attendant scrawny vegetation are also on my to-chart list. But I am curious about the ornament above them.

Now there were lots of other items on display in this exhibit, most of which I’ve seen in the BMFA’s on line photo collection – other stitchery, several modelbooks (all open to needle lace pages), lots of ceramics, and many paintings. Some of which from the “back stacks” – items not on usual display. It was grand to see them out and being admired. I admit I did not download the guided tour and didn’t buy the accompanying $45 book, but while there were lots of women depicted in these massed works, there were very few historical individuals described or shown.

I was hoping to learn more about (for example) what individual female members of the Italian mercantile nobility actually did, beyond being married for political alliances. There were a few portraits, but not much of the story behind the sitters’ identities (if known at all) was presented in the in-room captions. There was a smattering of works by female artists, but the majority of pieces were by men, depicting saints, virtues, and ideals – laudable and arguably strong, but not the personal presence I had hoped for. All in all it was a lovely exhibit, with tons of pieces that were interesting in and of themselves, but as an exhibit showing the power and reach of Renaissance Italian women, it came off more as an assemblage of things from their time, rather than a documentation of their lives, ambitions, and accomplishments.

BUZZ ON BEESWAX

I keep seeing questions about waxing threads on various social media needlework discussion groups. I usually end up retyping this. So to make reference easier while offering up this Helpful Hint, I take the time to write it out in long form.

I use beeswax on my threads for blackwork and cross stitch. I only use 100% beeswax, not candles or other beeswax products that often contain fragrances, colors, or agents to soften (or harden) the wax. Whenever possible I buy it direct from beekeepers, at farmers’ markets or county agricultural fairs, avoiding the overpriced boxed or containerized offerings at big box craft and sewing stores. I’ve also bought it via Etsy and Amazon, but am leery of super-low priced imports that might contain adulterations. I look for domestic producers with a range of local bee-related products instead, especially those who guarantee the purity of their product. Even then it’s not a very expensive purchase. A one-ounce mini log is currently running between $1.50 to $2.00, and will last for years and years. By contrast those Dritz plastic containers of wax with no ingredient labeling are about $5.00 for an unweighed bit I estimate to be less than 25% of the mass of the one-ounce mini logs.

What does beeswax do for me?

- It tames surface fuzz on my threads, making them sleeker and smoother.

- It aids in needle threading, making that much easier and quicker.

- It cuts down on differential feed when using two plies of thread together. That means that both plies are used at the same rate, and I am less likely to end up with one extremely shorter than the other after a length of stitching.

- It eases thread passage through the fabric and “encourages” threads to lie next to each other in mutual holes rather than earlier threads being pierced by successor stitches. I find this leads to neater junctions in double running stitch and neater stitch differentiation in cross stitch.

- Since I stitch with one hand above and one hand below, occasionally the working thread is “nipped” as it is passed back from the unseen back to the front. A problem that leads to work-stopping knots and snarls that have to be teased out. Waxing cuts way down on this because the thread fibers are kept closer and are more difficult to snag.

- Less drag from less fuzz and eased passage through the work allows me to use a longer length of thread than I can get away with without waxing. Even a little bit of extra length before the thread degrades enough to make the work messy makes it easier to achieve a uniform appearance when working the second pass of double running, or doing the “return leg” of a line of cross stitches.

I wax my threads for blackwork and cross stitch: cotton, silk, faux art silk (aka rayon), linen – everything except wool. Note that I tend to work on higher count grounds rarely venturing below ground thread counts of 32 per inch (16 stitches per inch when done over 2×2 threads), and usually in the 38-46 range, sometimes up to 72 threads per inch (18 to 23, and up to 36 stitches per inch respectively). My blackwork and cross stitches are relatively short, so thread sheen is not a factor. If I am working satin stitch, or a longer linear stitch that takes advantage of thread directionality and sheen, like satin stitch, I skip the wax.

I usually keep two of those single-ounce logs going – one for dark colors, the other for light because even the best threads will crock dye and leave traces of lint in the wax as I use it. Since I do a lot of blackwork with strong colors, I don’t want to run a white, yellow or other delicately tinted thread through the accumulated color left behind by the darker ones. Below is a one-ounce mini log, untouched; and the remains of an identical log after about seven years of very heavy, daily use. The frugal will note that there’s more than enough in one mini log to break it in half, and use one piece for dark colors and the other for light, but that’s not what I did here. That grungy little stub used to look exactly like its brother. It’s so filthy now I may break down and melt the stub, skim off the lint and recast it in a silicon baking mold.

Applying wax to working threads is quite simple. I hold the bar in my hand, with the thread to be waxed between my thumb and the bar, under gentle pressure. Then I use the other hand to pull the thread across the surface of the wax once or twice. I don’t want to wax heavily – there should NOT be flecks of wax on the thread, and it should not feel stiff as a wick. In fact, after I thread my needle I usually run it once or twice through a scrap of waste cloth before use to remove any that might be there, before using the lightly waxed thread on my project at hand.

Back to when to use and when not to use beeswax. Here are a couple of examples. First, my project-in-waiting – the Italian green leafy piece. Lots of satin stitch. The dark green outlines are two plies of Au ver a Soie’s Soie D’Alger multistrand silk floss on 40 count linen (over 2×2 threads). Wax on all the outlines, even though they are silk. That infilled satin stitch worked after the outlines are laid out? More of the incredibly inexpensive Cifonda “Art Silk” rayon I found in India. No wax on the satin stitch. That lives or dies by thread sheen and directionality. While the stuff is very unruly and I do wax it when I have used it for double running or to couch down gold and spangles on my recent coif project, here doing so would not give me this smooth and shiny result.

And an example from the coif mentioned above. It’s on a considerably finer ground – 72×74 tpi. All of the fills are done in one strand of Au Ver a Soie’s Soie Surfine in double running. All waxed. The black outlines on the flowers and leaves are two plies of the latest batch of four-ply hand-dyed black silk from Golden Schelle, done in reverse chain stitch. Also waxed. The yellow thread affixing the sequins and used to couch the gold, the same Cifonda rayon “silk” used in the leafy piece, waxed, too. The black threads whipping the couched gold are two plies of Soie Surfine, waxed. But the heavy reeled silk thread ysed for the outline is Tied to History’s Allori Bella Silk. It’s divisible, and I probably didn’t do it as the maker intended, but that’s two two-ply strands, plus a single ply teased from a two-ply strand – 3 in all – worked in heavy reverse chain. That’s a longer stitch, thicker than even the black flower outlines, and because the stitch was long and I wanted to make it stand out from the other black bits, shine was part of what I needed. NOT waxed.

Many people have asked me if waxing makes the piece collect dust faster, leads to color migration, or makes the stitching feel heavy and well…. waxy, or if it stains the cloth when the piece is ironed. My answer is that I find no difference in dust accumulation on my finished pieces on display. And I see no color change, either. Beeswax has been used for stitching for hundreds of years with no ill effect that I have seen reported. Modern substitute thread conditioning products of unknown composition have not undergone that test of time.

As for a heavy, waxy feel – again, no. Not if you apply it lightly. I do cover my stitching with a piece of protective muslin when I iron it, and never iron pieces on which I’ve used the Art Silk anyway. I have never noticed waxy lines of residue on my ironing cloth when I have ironed my cotton, linen, or silk pieces.

So there it is. Waxing, why and how I do it. Your mileage may vary, of course.

THINKING, BUT KEEPING BUSY

A couple of people have asked if I’m taking a break from needlework in the aftermath of the great coif project.

Nope. To be truthful, I am filling my time with far less challenging pieces while I contemplate the next big project.

First, I’ve returned to the third forehead cloth. I’ve done two before and love wearing them instead of bandannas to contain my hair on windy days. I do a little bit on them in the afternoons, and in the evening catch up on my sock knitting.

The socks are my standard issue toe-ups on anything from 76 to 88 stitches around, depending on needle size; figure-8 toe (an technique unjustly despised by many), plain stockinette foot, German short row heel, then something interesting for the ankle. Mostly improvised. The only hard part is remembering what I did on that ankle so I can repeat it on the second sock.

The forehead cloth is fairly flying. It’s all one pattern, on cotton/linen yard goods that works out to about 32 threads per inch. That’s as big as logs compared to the coif’s linen. I’m trying out Sulky 30 thread (two strands). It’s ok, but I am not so fond of it I’d throw over softer, more fluid flosses. I am betting though that it will stand up to hard laundering better than standard cotton floss. The stitching on my other two forehead cloths, done in silk, has survived quite nicely. Unfortunately the ties – folded strips of the same ground – have totally shredded and been replaced twice on each. I may move to narrow store-bought twill tape for the ties, instead. Jury on that is still out. Oh, and yes, there are mistakes on this. Some I’ll fix, and some I won’t. Have fun hunting for them. 🙂

While I’m here, I’ll share a tiny blackwork hint.

I’m doing double running but this will be relevant to those who favor back stitch, too. See those “legs” sticking out in the photo above? As I passed those junction points I knew I would be coming back again, from a different direction. It is far more difficult to hit the exact right spot when joining a new stitch to an existing stitched line (both perpendicular as here, and diagonally) than it is to mate up to a stitch end. Those legs are there so when I come by again I have a clear and simple target for the point of attachment. This saves a lot of time, minimizes my errors and helps keep my junctions as neat as possible. Try it, I think you’ll find the trick useful.

What am I contemplating for my next project? Possibly a blackwork/sashiko hybrid. I have a barrel chair, a wreck salvaged from the trash, that I had recovered in Haitian Cotton back in the early 1980s. It has survived four house moves and two children, but although the back and sides are in good shape, the seat cover and the area just under the seat are both shot. I still adore the thing even though it doesn’t really fit in with the rest of the house’s style. So it’s going up into my office. I plan on recovering the shredded areas with patchwork denim overworked in white running stitch. The denim will be reclaimed from various outgrown and destroyed garments I’ve held onto against just such a future need. Since I do not plan on replacing the rest of the upholstery, I’m counting on those flashes of white to bring the seat and the rest of the piece together.

ANOTHER PORTRAIT, ANOTHER REDACTION

About a year ago a member of the Italian Renaissance era fashion discussion group, Loggia Veccio on Facebook asked for help decoding the blackwork on the sleeves of this portrait. I volunteered, but heard nothing back. Today she came forward again to repeat her request. So I oblige.

The first thing I did was try to find the full attribution for the portrait, plus a better, higher resolution image than this repasted one.

The original is held by the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, Accession K1651. While it’s not available on the museum’s own website, it does have a page in the Art UK on line collection. The accompanying information cites its date as circa 1500, and the working title as “Portrait of an Unknown Young Woman.” The blurb goes on to say that it has some congruence with works produced by Carpaccio, but stops short of definitively identifying the painting as his.

On to that sleeve. It’s a relatively simple pattern, but redacting from paintings is never as easy as doing so from an actual textile. In this case while the design looks quite regular at gazing distance, up close examination shows that multiple interpretations of the repeat are represented. I’ve attempted to reduce those to a most probable approximation, but it is just an approximation.

As usual, my assumptions were square units, all of the same size, mirrored both horizontally and vertically. I further assumed no diagonals based on the stepwise total appearance. And while I first thought this might have been done in one continuous line, examination of multiple repeats showed that it was most probably done as lozenges rather than a united whole, with small “islands” filling in between the main bird-bearing motif. Here is my best guess.

As usual, a printable page with the pattern and accompanying text is available by clicking here, or popping over to my Embroidery Patterns tab.

ANOTHER FOA FAMILY ARTIFACT

A while back I did a long post on a design cluster that appears in Italian work of the 1500s to 1600s. It’s characterized by thin stems, grape leaves, striated flowers, curls, and occasionally, infilling in multiple colors. Here are some examples of the style family, and how they have fared in my hands.

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Accession 1894-30-114.

The museum dates this (a bit improbably) as being 14th century, Italian. I would bet that attribution hasn’t been revisited since acquisition in 1894. Here’s my in-process rendition of it (my own redaction).

There’s also this piece in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accession 51449.71.1.4. The Embroiderer’s Guild has another piece of what may be the same original in their archives. The MET dates this as 16th century, Italian. The photo below is my rendition of this work – my own redaction, in T2CM – the original photo is not as clear.

Finally we have this one. It’s in the Jewish Museum in New York, Accession F-4927. The original bears an embroidered date in the Jewish calendar, so there’s no quibbling with the point of temporal origin. It’s labeled Italy, 1582/83. Again, here’s my workup of my own redaction.

This last piece is a Torah binder, a decorative strap to hold the scroll together in between uses. The bundled scroll and its rollers would have been further protected by a richly embroidered covering, and if the congregation could afford it, adorned with a silver front plate, crown, and reading pointer. Making and/or commissioning such things was both a great good deed and a point of family prestige. In addition to the date, the binder bears the dedication” In honor of the pure Torah, my hand raised an offering, Honorata… wife of… Samuel Foa, it is such a little one.” The museum’s blurb notes that Italian Jewish women often were donors of important textiles and other objects, doing so to commemorate family births or marriages.

When I first wrote about these objects I noted that Honorata Foa might have commissioned the work, or might have done it herself. With so little data available, it would be difficult to make that determination.

Now however, I’ve stumbled across another stitched item credited to a Foa family matriarch. This one is later. Although it is still a foliate meander, is clearly of a later style, surface embroidery, and not counted. It’s in the MET’s collection, accession 2013.1143. Excerpt of the museum’s photo below.

It too bears an inscription and specific date. The museum blurb translates it as “Miriam, of the House of Foa, took an offering from that which came into her hands; and she gave it to her husband, Avram. The year of peace (5376) to the lover of Torah.” The date equates to 1615/16 on the common calendar. The museum entertains the thought that Miriam might have been the embroiderer, herself.

I was amazed to find two pieces donated by the same family, 33 years apart, showing so strongly the major stylistic shift in stitching that was taking place over that time. I also feel a bit more confident about attributing the earlier piece to Honorata’s hand.

I‘ve found some other material about a Foa family that flourished in Sabbioneta, Italy in the mid to late 1500s, with an extensive business in printing bibles and prayer books. But the only textile work the publisher’s blurb mentions (but doesn’t show) is a tapestry covered bible. I may have to get the book it cites, a family chronicle written by Eleanor Foa, a modern day descendent. I’ve also found a reference to Eugenie Foa, a fiction writer of the 1800s, who wrote about French Jewish life, setting Esther, one of her characters, in an embroidery workshop. But the full text is behind permissions I don’t have (the Google link to the full text mentions Esther in Foa’s work, but the linked blurb does not). Other works that mention the modern Foa family and its scions trace origins back to the publishers of Sabbioneta, but do not mention any link to handwork.

There’s clearly a slew of thesis topics here for someone who wants to take it up: the Foa family and its involvement in the hand embroidery industry of the time. Was the prominent printing family also involved in embroidery, or was it another similarly named/possibly related branch? Was the leafy grape design cluster something from their (posited) workshop? Are there other extant products from or writings by family members? (I’d fair faint away if there was a modelbook of embroidery designs among their archives). Did the family persist in its embroidery vocation over time? If so, how did their products evolve?

As ever research rarely answers more questions than it evokes.

UPDATE: Honorata Foa’s Torah binder will be on display at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, as part of their Strong Women in Renaissance Italy exhibit, 9 October 2023, through 7 January 2024. Although the museum’s page doesn’t show it, an article in the New York Times offered an in-gallery photo of the piece. Amazing, since I had no idea that this was happening until after I posted this blog entry.

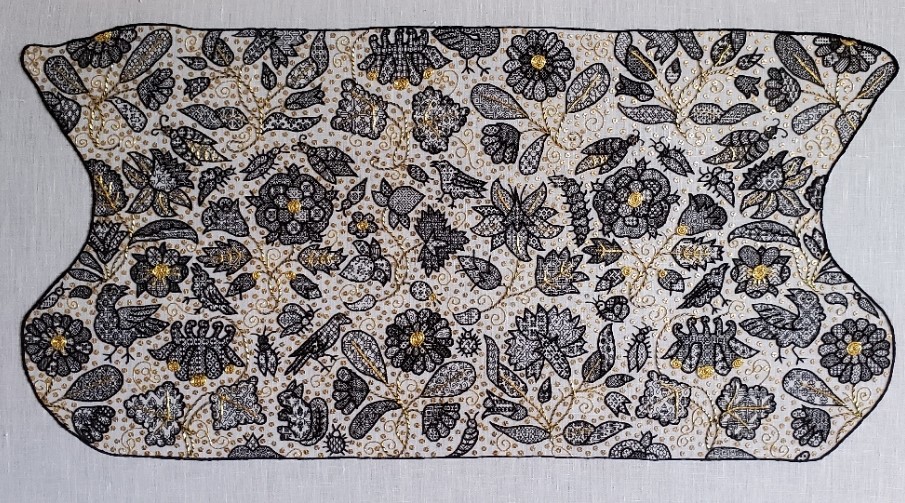

UNSTITCHED COIF – FINISH. THE FILLS

As promised here’s the breakdown of the design, motif by motif – a guided tour of what I was thinking or not thinking about. This is turning out to be way longer than I expected. Feel free to scroll down to the eye candy and ignore the prose.

First, on the general aesthetics, I already confessed yesterday that this piece is a departure from the strictly historical, using stitches, materials, and fills that have no specific point source in a particular artifact contemporary (or near contemporary) with the original Victoria and Albert Museum piece of ink-drawn linen. But in spite of that I’ve tried to stick to general aesthetic. It was a time of “more is more.” Pieces like this coif were status items that proclaimed the wearer’s wealth. I heard Thistle Thread’s Tricia Wilson Nguyen lecture at Winterthur about how copious precious metal spangles, threads, and even lace served as walking bank accounts, shouting prosperity but still being available as liquid capital to an owner whose fortunes dipped so low that reaching for a scissors to snip off a bit for ready cash was a welcome option. To that end, I’ve doubled down on the gold accents. But not being as flush as landed gentry from the late 1500s, I’ve used imitation gold thread and gold tone mylar rounds.

I’ve also tried to emulate the more lush aspects of some historical blackwork pieces, that created depth and shaded nuance by using fills of different visual density, augmenting the effect with raised outlines. I would have liked to use a plaited stitch for the stems, but it’s clear that the original artisan didn’t leave room for them, so I settled on outlines that were markedly heavier than the fills, topped off by a whole-piece outline that was even thicker and more dimensional.

I also like the difference in blacks used. The fills in the thin modern-dyed spun silk single strand are dark enough to look lacy and contrast well with the ground. The outlines, done in the boutique, small batch historically dyed double strand (also spun) are a much softer black. In some places the black takes on a reddish or brownish tinge, or moderates to an even less dense charcoal. If they were as deeply toned as the fills I think that each leaf, petal, or wing would present more as a grey-scale visual mass rather than letting the fills speak louder than the outlines. Finally the deeply black modern dyed but glossier reeled filament silk used in the perimeter then echoes the black of the fills, and makes a world of difference to the piece, pulling it all together. All black, all different, and all contrasting with each other.

On planning and fill selection, I winged it. I didn’t sit down and plan anything. I picked fills on the fly, with only a vague idea of where I would put dense, sparse, and intermediate fills as I began each sprig or group. Some succeeded quite nicely, others I would re-do differently had I the chance. Would I ever sit down and plan an entire project’s density/darkness/shading map ahead of time to avoid this? Probably not. It’s more fun to bungee-jump stitch.

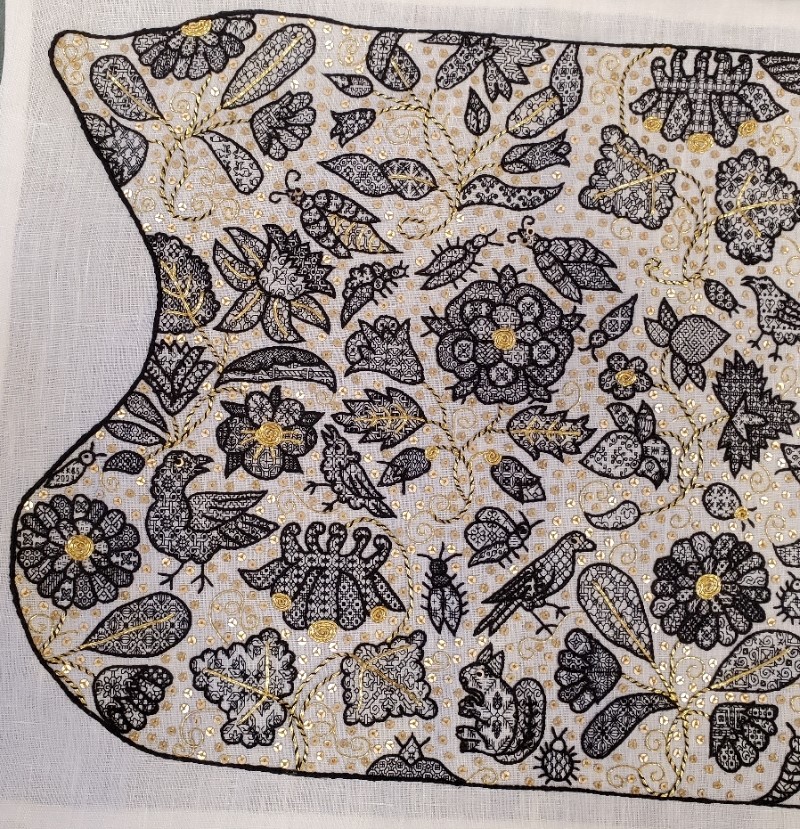

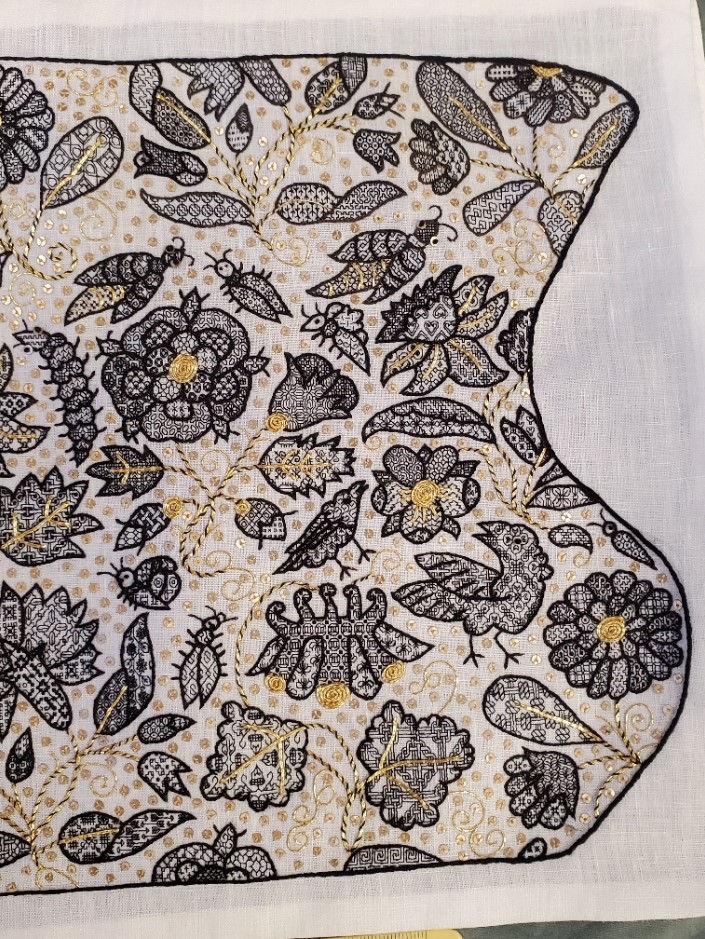

On to the piece. First a quick recap of the whole item:

On this whole coif shot I can see three center circles of motion in the design, one surrounding each rose, and one surrounding the two centermost unique motifs – the borage flower/strawberry pair. The rest of the flowers are surrounding those elements. Maybe I see them because I’ve been staring at the thing for so long, or maybe my admittedly ornate but heavily outlined rendition with the gold whipped stems sinking into the background pulls those surrounds forward. When the exhibit comes around and I can see all the other pieces it will be interesting to see what other symmetries they accentuate.

We’ll start at the upper left. Although I began at the lower right, it’s easier to walk across starting at this point. I give fill counts and cite the number of fills I used from the project’s official website. Now some of the ones in my doodle notebooks duplicate or near duplicate those (we were after all mining very similar sources), so I apologize if any double-listed ones ended up in the wrong pile.

The first motif in the upper left I have been told is a marigold, one of six on the piece. It’s truncated at the edge by the indent. The marigolds were especially hard to work because those little jelly bean spaces of their petals were so tiny that most of the fills I had included repeats too large to be useful for them. I tended to use four repeats in the outer petal ring, repeating the sequence four times. The inner ring used different fills, usually two. Fourteen fills in this motif, twelve are mine, including the bunny rabbits. The other two are from the collections redacted by Toni Buckby, our Fearless Leader, and are available at the Unstitched Coif project website.

Immediately to right of the partial marigold in the corner is a truncated carnation or gillyflower (hard to tell them apart). Three of these are here, but only one isn’t cut by the perimeter. At this point, relatively late in my stitching I went out on the hunt for additional fills, and redacted a couple of pages of them for the upcoming third Ensamplario Atlantio volume. One of particular note is the leaf at the lower right, with that flying chevron shape, one of several I drafted up from a photo of a blackwork sampler, “Detached Geometric Patterns and Italianate Border Designs with Alphabet” 1697. National Trust Collections, Montacute House, Somerset, NT 597706. The twist and box of the sepal is from the same source. Yes, I know they are later than the coif’s original. Since by definition anything I doodle is even later still, I didn’t see the harm it using them. 18 fills total in this sprig, six from Toni’s redactions, two from mine, and ten of my own doodles.

Next to the right on this photo cut is a columbine. It’s barely snipped, and one of three on the piece. The large leaves made good showcases for some of the bigger repeats, even with the gold overstitching. As a result on this sprig we’ve got only five fills, two of which are from Toni’s pages. On this motif as on all of them, I tried to use fills of contrasting effect. Here in the flower we have the very strong linear grid of the main pattern, paired with the angular acorn spot motif. This flower is also an example of introducing movement or syncopation by NOT using the same grid for adjacent motifs.

Back to the left edge now. This sprig includes a narcissus or daffodil, plus a viola and something indeterminant, possibly a blossoming narcissus, all on one stem. Leaves are also of multiple forms. There are only two of this hybrid sprig on the piece, both nipped by their respective edges. All those little areas add up to 19 fills on this one. I’m particularly happy with the density effects I got on this one, with the narcissus throat, the leaf curl, and the viola sepals bringing darker depth. I did try to find two patterns of similar density for the lower petals on the narcissus, too. I have to look closely to remind myself that they are two petals of one design and three of another.

Next over is the rose. I’ll come back to the bugs that surround it. There are two roses on the coif, and two tiny partial bits on the lower edge. In truth, I’m not enthused about the way the big flower turned out. I like the sepals and the outer ring of petals (three fills, all of the same tone), but the inner rings aren’t well differentiated – although I used one fill for all five of the middle ring and that isn’t bad, that inner ring with its three fills is rather boring. Were I to do it over again I’d make some different choices here. I used sixteen fills in all for this sprig, including two of Toni’s set.

The creatures dancing “ring around the rosie” includes seven bugs and two birds. Visually they do make a circle around the rose, with one larger bug flying off above the narcissus. Here I spy a mistake, and the thing being in transit right now, it’s too late to fix. I meant to go back and add little gold stripes to the body of the bug to the upper right of the rose. Those tiny bits of couching were the ones I liked least to do. So it goes.

Like the marigold petals, the body parts of all the coif’s bugs were a challenge. Some are so tiny that it’s hard to squeeze anything resembling a pattern into them. I doodled on those, but I tried hard to make the doodles unique. In a couple of cases I found I had made a duplicate of a pattern stitched before, and went back to make modifications to one of the inadvertent pair. All of the large bugs with sequin eyes have a feature in common. Although it’s hard to see because of the stripes, I used the same pattern for both of their wings, but rotated it 90-degrees to give them extra movement. I have found no historical precedent for using directional fillings this way. Taken as a group, there are 27 fills among all of these bugs and birds, four of which are from Toni’s pages.

Reading across, the strawberries are next. (I’ll cover the bird to its right in the next post). There is only one strawberry sprig on the project, and it’s another challenge because of the small petal and sepal spaces. This is another motif I count as only a partial success. I like the top strawberry, flower, and leaf, but I think I should have chosen differently for the lower strawberry. Possibly working the sepals for the second one and that leafy whatever that terminates the sprig both darker. That would have made the lighter fill in the bottom bud a bit more congruent. Thirteen fills in all, four of them from Toni.

Back to the left hand edge of the photo, below the narcissus/viola stem are the large bird, and the second marigold (cut off at the edge). There’s also a tiny bug above the marigold in which I worked “KBS 2023” as my signature. This flower was my finishing point – the last one stitched. Most of the fills in the petals were improvised on the spot. The bird carries an interlace and star I remember doing on my first large piece of blackwork, an underskirt forepart, back in 1976. That piece however was worked on a ground that was about 28 count (14 stitches per inch), not 72 count (36 stitches per inch). You may even recognize some of the other fills I reused on the coif in the snippet below. Vital stats on Marigold #2 – 12 fills for the whole sprig including the large bird, one of which is Toni’s.

The second columbine, to the right of the bird, grows from the bottom edge of the coif. I wonder how many people will look closely enough at the leaf on the left to realize that it’s bugs. I was thinking bees, but I’ve been told they read more like flies, and “ick.” There are four fills in this sprig, one of which is Toni’s.

Adjacent to the right we find Needles the Squirrel, his friend the round bug, and one of those rose snippets. I group them together for convenience. Needles’ pine spray fill is mine, and came about during discussions on line and in the Unstitched Coif group’s Zoom meet-ups. Someone mentioned using an acorn fill for their squirrel, but UK folk were quick to point out that the indigenous Red Squirrel, who preferentially dines on pine nuts, was deeply endangered by the invasive Grey Squirrel, who prefers acorns. So I doodled up the spray, shared it with the group, and used it on mine, bestowing the appropriate name. I’ll find out in December if anyone else used this fill. I also did the directional shift in Needles’ ears. There are only six fills in this group.

Marigold #3 is in the right corner of this photo. He’s also rather a mess. I should have picked two dark and two light fills for the outer ring of petals, instead of one dark one and three intermediates. I did rotate the direction of the fills around the circumference. Oh, the snails? A variant of those snails with their wrong-way curled shell is on the majority of my blackwork pieces. Not quite a signature, but not far from one, either. There are 17 fills in this sprig, one from Toni.

On to the center of the piece.

Back up to the top of the center strip. Here we have the sadly bisected bird, with the fourth marigold to its right. Although the petals are a bit uneven, I did try something specific with this one, using two fills in of similar density in the center ring, and four also similarly sparse fills in the outer ring. I count this one as a success. Together these two motifs contain 13 fills, two of which come from Toni’s pages.

Below the marigold is the singular borage flower. There’s only the one, and he’s at the center of it all. I will cover the caterpillar later. He’s one of my favorites in the piece. I especially want to call out the tiny paisley at the bottom of the stem. The fill there is one that Toni redacted from a coif, V&A Accession T. 12.1948. It is very unusual fill, with the exception of a few that use a circle of stitches radiating from a center hole sunburst style, it is the ONLY historical fill I have seen that uses the “knight’s move” stitch – two units by one unit, to produce a 30-degree angle. Knight’s move stitches are very common in modern blackwork, but exceedingly rare in historical pieces. Knowing this I’ve drafted up hundreds of fills and in keeping with this paucity, have only included them on three or four of the most egregiously modern. The little stirrups in that paisley open up a whole new world of possibilities. Borage contains 11 fills. Five of them including the stirrups are Toni’s.

At the bottom below the borage is Carnation #2, attended by four insects. I am also fond of this one, especially the long skinny bud on the lower left. That striped lozenge filling is one of Toni’s and I adore it. With all the folded leaves there was ample space to play with density, and it was fun to pick these fills on the fly. All the more so because the combos worked. The insects, from lower left, a caterpillar or worm, an amply legged spider, a moth, and a beetle, are a playful way of rounding out the space between the center and the side areas, the latter being (mostly) mirrored near-repeats. This group holds a whopping 23 fills, nine of them from Toni’s redaction page.

And back up to the top we go. Carnation #3, another truncated motif. Like the last carnation this one had a lot of play for contrast. It was actually among the earlier sprigs I stitched because I began upside down in what is now the upper right hand corner. This is the motif on which I began to get a better feel for the size of the repeats in the fills and how that size related to the dimensions of the shape to be filled. There are 19 fills in this one, including two of Toni’s.

Below this last carnation is Rose #2 and its bug and bird armada. Don’t worry, I am not double counting the moth I included with Carnation #2. I like this rose slightly better than the other one, but don’t count either one as a stunning success. I may excerpt the rose and try again. In any case you can see that I’ve hit full stride here in using fills of various repeat sizes.

For the most part I stitch fills then go back and outline them when the motif is complete. I have always found that to be a forgiving way of working that allows fig-leafing of the fills’ often all to ragged edges. But on the caterpillar (my favorite insect on the coif) I started at the head, stitched its fill, and then outlined it. I continued in this manner segment by segment. I did this because I knew if I waited until the end, my divisions between the body segments would get muddy. I wanted to make sure that the little center divots that ran down his back were seen. I probably wouldn’t have attempted this if I hadn’t seen others in the Unstitched Coif group Zoom meetings working up all of their outlines, then going back and adding fills.

Rose #2 and accompanying critters used 31 fills, including six from Toni’s pages.

Below and a bit to the right of the rose is Columbine #3, and a partial rose. There’s also a lump from which the columbine sprouts, but that may be a mistaken interpretation on my part. Perhaps that was supposed to be an arched stem. Maybe yes, and maybe no. I spent a lot of time dithering about how to handle the columbines. Those curly narrow top protrusions in particular limited the size of the repeats that could fill them effectively, especially if I wanted to play up the contrast between the gold topped and plain petals. The circle fill (one of Toni’s) worked nicely and set the tone for my later choices. In this grouping there are nine fills, including Toni’s circles.

Back up to the top for Marigold #5, which happens to be the first bit I stitched. The leaf with the larger butterflies was the first fill I did. When I started I thought that stitching over 2×2 threads might be problematic, so I worked this one over 3×3. However my eye and hand are SO attuned to 2×2 that it was clear that the new count would drive me to distraction, so I quickly switched to my standard. But I didn’t pick out the errant leaf. I doubt if I hadn’t mentioned it you would have noticed. In any case you can see that I was very tentative on fill repeat size on this first flower. For example, I could have used much larger repeats in the leaves. Still this was the try-out. I beta tested using fills aligned in radial directions, the gold center coil (here only a half), veining and stems in couched gold double strand, and curls in couched single strand. And adding spangles. Once they were in I noted how the stems disappeared, so I went back and whipped them with black to make them stand out a bit from the background. This sprig uses 15 fills.

Below the marigold is the second Daffodil/Narcissus and Viola sprig. I’m generally pleased with it, although I wish I had saved the feather fill for one of the birds. You will note that I take no special care in always whipping the stems in the same direction. I did them in the most convenient/least awkward direction because needle manipulation to avoid catching previously laid down work was very important. As I went on I destroyed most of the sequin/French knot eyes and some of the smaller couched gold bits by snagging them with my needle tip or smashing them with ham-handed stitching. I ended the project by replacing all of the eyes. There are 19 fills in this motif, two of which are from Toni’s pages.

Last but not least we have yet another marigold, Marigold #6 with bird, bug, and bits. I confess that the marigold was my least favorite to work, even by the time I did this one – only the second one I stitched. That little intrusion below the bud may also be a vagrant bit of curl or stem, but I filled it in anyway. This bird has the first sequin/french knot eye I did. I also experimented with three sizes of little seed beads, but decided that they were too dimensional and/or just too big for this use (the paillettes I used are only 2mm across). Our final motif has 19 fills, including one from Toni’s page.

That ends the guided tour. The total count of unique fills on this piece is 274. 51 of them are from the pages of fills redacted by our Fearless Leader, Toni, and posted on the project’s home website. The remaining 223 are mine, mostly taken from my Ensamplario Atlantio series.

Would I ever attempt something like this again? In a heartbeat. BUT I will never do another piece of this size and stitch count to deadline. While it was intensely fun every minute of the roughly 900 hours I was stitching, I prefer to stretch those hours out over a longer time period. Intense thanks to Toni and my fellow Unstitched Coif participants, for the opportunity, the learning experience, the encouragement, and the camaraderie. I am looking forward to the December exhibit, and to meeting as many of you as possible, in person.

When the flyer for the exhibit is released I will post it here on String, on Facebook, Instagram, and Linked In. In the mean time, reserve the date – it will be on December 18 through the 24th, at the Bloc Gallery, Sheffield Museums, Sheffield, UK.

UNSTITCHED COIF – FINISH! MATERIALS AND TECHNIQUES

here have I been these past weeks? Stitching away in a sweatshop of my own making. That may sound tedious, but it was actually tons of fun. I had to drone away with intent to meet the completion deadline for the Unstitched Coif project. I’ve completed the embroidery, including some small repairs. All that’s left is neatening up the back a bit, hemming to final size, and shipping.

This is the first of two posts on finish. The next one will present details and commentary, motif by motif. But I still have work to do before mailing, so that will have to wait for another morning.

Yes, that little dip in the upper left is in the original, too. And yes, it does bother me, but (near) verbatim is near verbatim, so I kept it instead of extrapolating what should have been there.

Materials:

- 2.25 spools of Au Ver a Soie’s Soie Surfine spun silk for the fillings, purchased from Needle in a Haystack.

- 1.3 hanks of Golden Schelle’s black four-ply spun silk embroidery floss for the motif outlines. It’s worth noting that this is a hand-dyed product, prepared from a historically documented iron/tannin recipe, and in 500 years will probably have eaten itself to death, exactly as black threads in museum artifacts from the 1500s have deteriorated over time. I love the minor color variation and soft black produced by their small-batch method.

- About 0.25 hank of Tied to History’s Allori Bella silk in black – a reeled filament silk for the heavy perimeter outline. This one claims to be four-ply but is hard to separate. Each ply appeared to be made of three strands. I ended up using two of these constituent strands at a time, which means I got six working threads out of a length of the four-ply.

- About 0.25 of a hank of Japanese Gold #5, from the Japanese Embroidery Center in Atlanta, Georgia.

- One skein of six-strand Cifonda Art Silk (probably rayon) in a light gold color. I bought this in India, as part of a large lot for short money.

- 1.9 strings of 2mm gold tone paillettes, from General Bead. The description says there are 1000 spangles per string. I doubt that. Probably more like 500. Still, that’s a lot of spangles.

- John James needles – #12 beading needles (outlines, spangles, couching), and #10 blunt point beading needles (fills, whipping). The #12s were labeled as being blunt points, too, but they wre far sharper than the #10s. Many of the #10s, because I kept bending them as I worked, and a bent needle is harder to aim accurately.

- Mani di Fati’s 72×74 count linen – as recommended by our Fearless Leader, Toni Buckby.

- Toni’s elegant rendition of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s “Unstitched Coif”, Accession T.844-1974, shared at this link by her special permission.

Stitches Used:

- Fills – mostly double running stitch, with occasional digressions into “Heresy Stitch” (aka half back stitch), back stitch, and wild improvisation when lack of real estate and undulating edges required shoehorning motifs into tiny spaces. With one exception they are all done over 2×2 threads. When I started I thought that over 3×3 might be better, but my brain and hands are so trained to work 2×2 that it drove me nuts, so I reverted to the smaller size. But I didn’t bother ripping out the completed bit. Have fun hunting for it.

- Motif outlines – Reverse chain. A probable departure from historical usage. Carey, in her excellent book Elizabethan Stitches calls out twisted reverse chain as having documented use in 16th century historical artifacts, but mentions plain old reverse chain as having no provenance in that time. Which does seem very odd to me.

- Leaf veins and other gold details overlaid on top of black stitching – Simple couching over a double strand of the gold. Ends plunged. Plunging is another deviation from the historical. I have been schooled now by several people that is a practice common to the mid 1800s, and not before. In the 1580s gold ends were neatly tucked under. Look at all the gold I used, and especially at the short lengths. I voted to save my sanity.

- Stems – Also simple couching, but whipped with two strands of the black Soie Surfine. Where the stem extends a leaf vein, a single line of couching was laid down, but only the stem part was whipped. I began doing this after I finished the first flower, complete with background spangles, and the stems disappeared in the riot of gold.

- Spangles – I affixed my paillettes with three straight stitches each, hopping all over like a water drop on a griddle. Since I almost never strand over this was painful to do, but the ground’s dense weave and light color of the Art Silk convinced me that unless the piece was backlit, it would not be seen. Again, a sanity move.

- Perimeter outline – Yet another historical departure. I originally wanted to do this in Ladder Stitch, but the Allori silk isn’t robust enough to display stitch detail, and the modern severe blackest-black color makes such attempts moot. So I went for double reverse chain, also called Heavy Chain in the RSN’s on line stitch reference, worked as close and small as I could to make a fluid, heavily raised dense line.

Fill Sources:

I used two sources. One is the set of sourced historical redactions Toni provided on the group’s official website. They represent about 18% of the designs I used.

But now is true confessions time, and certainly not a surprise to those who know me, although I’ve avoided mentioning this in our group’s Zoom meetings. About 82% are from my own free books – Ensamplario Atlantio, Volumes I and II, along with the not-yet released Volume III that I am working on right now. (I was circumspect because this project is Toni’s. I’m just one of the foot soldiers. The glory and renown belong to the general.) My 82% includes an estimated 2% on-the spot improvs I came up with to get out of a jam.

Why a jam? Because early on in this project I declared that I would not be repeating fills between motifs. A flower could have multiple petals in the same pattern, or a bug might have matching wings in a single pattern, but once that pattern hit the cloth and the motif was completed, it was “burned” and not used again on the rest of the piece. That made some anxious moments because there are A LOT of shapes to fill, especially small jelly bean sized ones. More than once I made an inadvertent duplication and rather than ripping out the work, had to mod the second showing so it would be distinct. Or I had to fill a particularly challenging tiny spot, and just winged it because nothing I had would show well there.

What’s Left to Do:

Taming this shameful back. Mostly tacking down those annoyingly fraying gold ends, to the best of my ability. Then hemming to the final dimensions required for display. Nothing fancy, no drawn work hems or anything like that.

And of course the second post in this series. But for now, off to lion tame my dandelion mat of frizzy gold ends.

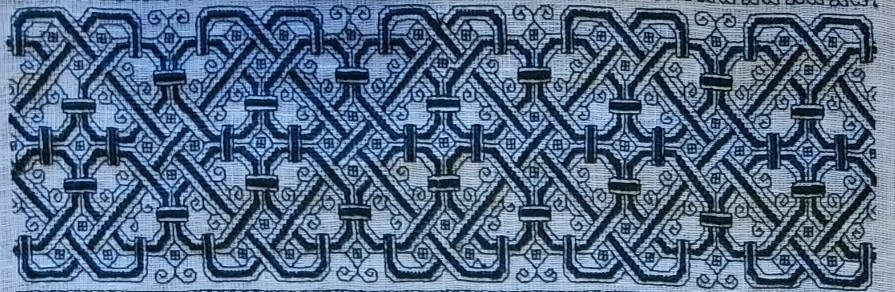

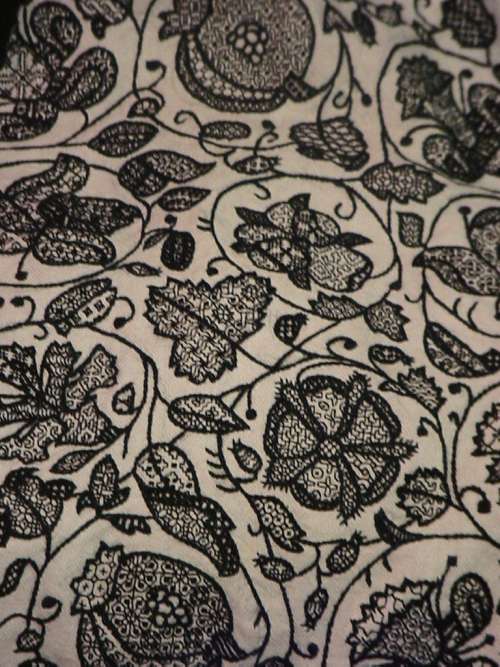

EVEN MORE ON AZEMMOUR

Yet another post only a stitching nerd will love.

Remember a while back, I pulled together some observations on the Azemmour Cluster? That’s a group of embroideries, usually known as fragments rather than whole cushions or other items. Those fragments were among the bits largely collected during the era of the Grand Tour (roughly 1870s up through World War I and on to the 1920s) when monied folk would do a season in Europe, collecting artworks and other items of interest. Needlework and lace collection were among those passions, along with other more traditional forms of art. Those gleaningss eventually landed in museums.

Since needlework fragments are not among the items most highly prized in museum collections, many remained in storage cabinets, with the donor’s provenance notes unchallenged. Or they did until museums began photographing these holdings both for their own use, and to post on line. At that time many of the attributions came under scrutiny, and did not hold up. In the past thirty-plus years I’ve been nosing these up, comparing them and making notes I’ve seen dozens of museum tags specifying stitches, dates, and places of origin change.

Among these collected and sometimes reclassified pieces were items in what some call the Azemmour Cluster. They were scraps sold to unwitting tourist-collectors as genuine late Medieval through Renaissance artifacts. But in actuality it does look like a lot of them, and a lot of the most represented designs in those museum back room cabinets, were produced in Morocco, with many dating to the late 1700s at the earliest, but most were likely made in the 1800s.

To be fair, the designs DO look like they express Renaissance roots. In the post above I even point out a piece that looks like it may be a predecessor. The Moroccan connection was known for some of these. Frieda Lipperheide in Old Italian Patterns for Linen Embroidery does point out that origin for some strips, noting their similarity to Italian designs.

Well, thanks to discussions in the Zoom meetings that are part of the Unstitched Coif project, a significant arguments strengthening the joint Moroccan sojurn of these designs has come to my attention.

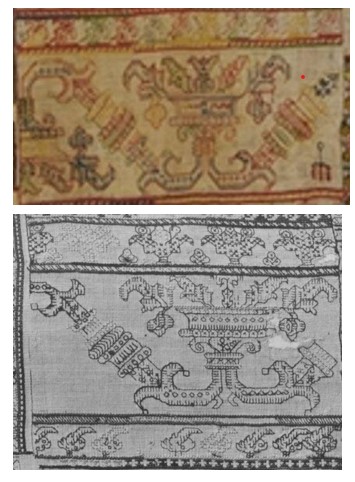

Here are two samplers from the Victoria and Albert Museum’s collection. The images are theirs used here under fair use/academic auspices. The multicolor one is Accession T.35-1933, a 19th century piece from Morocco, stitched in silk on linen. Yes, most of the individual fragments of these designs are in monotone, usually red, but occasionally deep indigo, these two samplers with their collections of many designs are happy riots of color.

This black and white photo is also of a multicolor piece (Accession 372-1905), dated from the 1800s, and is also listed as of Moroccan origin.

Both of these pieces contain two of the most common motifs in the cluster. This one is what I call the Spider Flower, for its spindly center blossom.

Here’s the second. I call it Wide Meander. This is found both with the wide strip looking rather sea-monster like with a gaping mouth, and in a tamer form, where the monsters have fused to become a super-wide belt like meander join. Discussions of both Wide Meander and Spider Flower are in my previous Azemmour post. Earlier musings on the Spider flower are here.

But these are not the only ones. The multicolor photo also has these two designs on it that I’ve discussed before.

The one on top is a variant of a pattern that is of Italian provenance. I mention it in this piece, and again in my discussion of voided grounds (under the boxed fill).

The one underneath I call the Pomegranate Meander. It’s clearly related to the Spider Flower, although in this case the ornaments on the joining diagonals are emphasized, rather than the center flower shape. It’s also mentioned in the Azemmour discussion cited earlier.

Plus it’s also worth noting that both of these V&A samplers show lots of variants of the customary accompanying borders so often seen with these main strip designs.

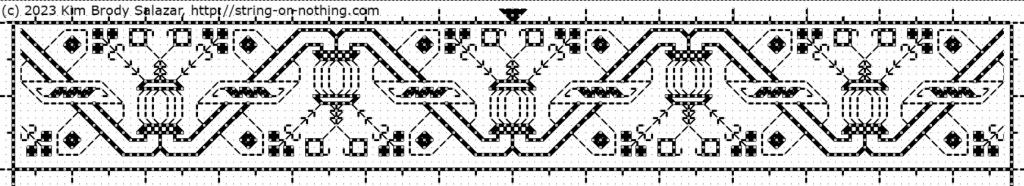

But for me the eye opener was the addition of another design to the group. Both samplers show the wide urn design.

This one I should have tweaked to based on the style of detail in the foreground. But I did graph it up for The Second Carolingian Modelbook based on this example from the Hermitage Museum, and accepted their identification as Italian, 16th to 17th century. Accession T-2714, entitled “Border Embroidered with Bowl and Stylized Plant Motifs” if the link breaks).

Here is my own rendition of this design, as I stitched it on my long green sampler.

Now we have a conundrum. We have many items whose dates and places have been corrected in museum collections. We have a continuing tradition of design replication and pattern re-use in a specific place. We have some predecessor designs and traditions that might have fed the Moroccan styles. And we even have some evidence of the post-Inquisition diaspora spreading these stitching styles TO settlements in Morocco. The Jewish link is cited by The Textile Museum of Canada. The Jewish Virtual Library notes the migration and community. The Jewish link is also mentioned here. The Textile Research Centre writes that production of Azemmour pieces died out in the mid 1900s, although recent revivals have been undertaken.

So where do we draw the line? Are these related items ALL to be reassigned to the Azemmour Cluster, with production dates in the 1700s through 1800s, sold to the unsuspecting as older artifacts? Are some possibly earlier, transitional pieces? Can we rely on just the wealth of ornament in the foreground of these strips to differentiate them from earlier forbearer pieces? Without detailed textile forensics, we may never know. But wherever and whenever their points of origin, it’s nice to see the family reunited again.

HALF A BIRD AND MORE ON WORKING METHOD

This poor little bird at the top had the bad happenstance of appearing on the edge line of the Unstitched Coif outline cartoon. He’s been horizontally bisected. I felt bad for him so I used an especially playful fill on his body.

Obviously I’m still soldiering on.

No doubt about it, 2×2 countwork on 70+ thread per inch linen moves along slowly. But I am about to hit two major milestones. The first is 50% completion. That’s just a couple of flower sprigs away. The second is consumption of my first full 100 meter spool of Au Ver a Soie’s Soie Surfine – the ultra-fine silk I am using for the fills. I have more than enough in reserve to continue on, so no supply side worries loom.

I’m now pretty well adapted to the magnifiers, but even so a forehead break every 20 minutes or so is needed. The headband mount stays seated in my optimum viewing range longer and and accommodates use of my usual bifocals, much better than using the glasses frame “arms.” Neither is comfortable, but I’ll pick discomfort + better sight every time.

I do wish that the magnifier would eat batteries more slowly. I only use the supplemental LEDs on the magnifier when working actual countwork in suboptimal light conditions. I don’t need the extra illumination when working the outlines or doing the goldwork and spangles. But even so, one set of three tiny coin batteries lasts for only about four days of stitching – roughly 14 to 16 hours. If I had a do-over I’d buy something with the same magnification levels, but that came equipped with a rechargeable light source. It would be very handy to plug it in each night and be ready for the next day’s stitching.

I still haven’t repeated fills between sprigs or insects (with one tiny exception). Folk have asked where I’ve gotten them, and how I use them (planning/choice and execution).

The sources for the fills I’ve used include the set painstakingly drafted out by our Fearless Leader, from close observation of select Actual Artifacts in the Victoria & Albert Museum’s collection. She has provided them as part of the tool set for this project. But I have to admit that the overwhelming majority of the fills I have used come from my own doodle notebooks, including the Ensamplario Atlantio series. Others I’ve improvised as I stitched, noodling up something unique to fill a difficult to render petal or bug body segment.

I reiterate that I am not sitting down and planning placements ahead of time. Nor am I drawing out the shapes on paper, then penciling in fills and stitching from those plans. I’m deciding on them as I come upon the spaces. Occasionally I get to a flower and say, “Hmm. Six segments, I can do six fills, three fills twice, or two fills three times.” Then I pick a treatment, and go looking for the first fill. In general I start with the largest segment of the design, pick something demonstrative for that space – roughly centering placement of the design by eye and working out from there; then select designs for the accompanying spaces to contrast or compliment. Take the Borage flower, for example:

I started this one by doing the big leaf with the interlace fill. That one is from my doodle notebooks. It’s a grand fellow, and one of my favorites. I was waiting for a suitably large space to use it, so in it went. And no, I didn’t mind that it would be partly overworked with gold for the veins. It’s bold enough to stand up to that treatment.

Next I turned to the flower itself, starting with the largest downward extending petal in the center. I used one of the fills provided by the project leader, graphed from V&A accession T.230-1929, a sampler of fill designs. It’s six from the end on this page. It’s repeat is smaller than that in the leaf, but it still needs room to play. I also chose it because I liked the way its spiky linearity contrasted with the closed, boxy interlace nearby.

While I was working the first petal, I decided to divide the flower into a set of three petals, two petals, and four petal/sepals, and shade them so the set of four would be the darkest, and “recede” to the back. I worked the other two petals of the three-set with the same design I just completed, then went looking for a lighter, less dense one for the two-set, ending up with another from my doodle notebooks. It’s light and airy, and quite quick to stitch up. Although it uses a lot of lines and has squares, it is a nice complementing contrast with the first design, and it had enough space to let the design show. It was clear with these five petals done that the four-set would need to be significantly darker and smaller, but I didn’t want to do a tiny repeat because I’m saving those for the many-tiny-petals Marigold flowers. I found a small, dense one, again from my doodles.

With all of the petals done, I thought that a darker center “cone” was in order. I pawed through the project collections and my notebooks but didn’t see anything tasty, so I just improvised this final fill, starting with the familiar cross and circle base, and adding detail until I got the density I wanted. (I did add it to my current notes, though.) The feel of it is almost the opposite of the star-like fill I used in the four-set petal/sepals. Once the final fill was completed, I went back and worked the black raised outline in reverse chain, using two separable strands of a thicker four-strand silk floss, hand dyed by a friend of mine (a softer black from a historically accurate iron/tannin recipe).

On to the bud. All three of the designs I used in it are from my notebooks, although the bud design is very common, and a feather-line variant of it is in the project’s collection of designs from V&A Accession T.82-1924 (a cushion cover). Again, I picked three in ascending density from the base to the bud tip, looking for ones that contrasted both in tonal value and in composition. As per usual, the outlines were last.

The small paisley at the sprig’s base was last. Originally I had intended to use its fill elsewhere, but I decided to employ it as a stand-alone because it is Very Special. It’s from the project collections, drawn from V&A Accession T.12-1948 (a coif) by our Fearless Leader. It’s third from the end on this page.

It’s special because of the stitches used to form the center X in the double stirrup shaped motifs. Those are two 1 unit by 2 unit stitches, crossing in the center. I call them “knight’s move” stitches. They are vanishingly rare in historical count work, appearing most often as a component of eyelet type constructs, where many stitches radiate from a single center hole. But stand-alone? This is the FIRST time I’ve encountered one on an actual artifact or contemporary pattern graph. Yes, they are quite common in modern blackwork and strapwork because they add an angle to the designer’s toolbox. It’s a very useful and graceful angle that many designers employ to excellent effect (especially Banu Demirel of Seba Designs), but to my eye, they produce a different overall look and are a clear marker of modern design. So finding one here was like being slapped Monty Python style, with a flounder.

I shared the observation with our group leader, who I am sure is now on the lookout for other knight’s move examples. Until there’s a whole vocabulary of them though, I will view this fill as the exception that proves the rule, and continue to eschew anything but 45- 90- and 180- degree angles in my own design work.

Once all of the fills and their black outlines were done, I added the gold. First I couched down the doubled gold of the flower’s petal lines. Then doubled gold for the leaf veins/stems. I affix them all with small stitches of gold color faux silk. Leaf veins that meet up with stems are done as one length, with that center line being laid down first. I add the “crossbars” by teasing them underneath the centerline using a tiny thread crochet hook, then couching down their arms. Once all he double-strand work is done I add the single-strand gold curls. The final step is to whip JUST the stem portions of the sprig with two strands of the same Soie Surfine I am using single stranded for the fills. Those black stitches are not structural. They are just for effect, binding the flowers and leaves together and uniting the sprig and make it stand out from the ever encroaching flood of paillettes/spangles.

And yes, I will go back and add the gold curl at the tip of the paisley. But it encroaches too closely on neighboring design elements, and I don’t want to catch it as I stitch those. So it will be added later.

I hope this answers the questions about my “bungee jump” approach to this large and complex project. As with any such banquet, taking lots of small bites is a fun way to graze across the entire spread.

YET ANOTHER BLACKWORK PATTERN INTERPRETATION

A big thank you to the Facebook/Blogspot guru who posts at Attire’s Mind. Today he posted a painting from the collection of the National Gallery of Art, (Accession 1931.1.114 in case the links break). It’s a devotional image by Giovanni Battista Morini, and is entitled “A Gentleman in Adoration before the Madonna.” It’s dated to 1560.

The Attire’s Mind post called out the blackwork on cuffs and collar.

Of course I was smitten with the pattern and had to graph as close an approximation of it as I could. It’s got a bit of interpretation, but given that the original I am working from is paint and not countable linen, I think that relying on best-effort/logical construction that achieves the motifs using the least real estate is good enough.

This one is especially interesting because it looks like the artist went out of his way to depict two line thicknesses. These could have been achieved by using different stitches, or by varying thread thickness. I’ve tried to convey that look by using two line thicknesses in my chart. Experimentation with how to render this in real stitching would be lots of fun.

Now, I could save this along for eventual publication in The THIRD Carolingian Modelbook, which I’ve already begun compiling, but given my dismal track record of decade-plus production for each of that series’ two prior volumes, why wait?

You can click here to download this as an easy single page PDF file

It’s also available on my Embroidery Patterns page. Enjoy!